This is Part 11 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Kisha Tracy. You can find the rest of the series here.

Why is there so much spousal abuse in medieval literature?

If you’ve watched Game of Thrones or practically any pop-culture version of the Middle Ages lately, you might reply simply that the Middle Ages were just all-around violent—especially towards women. Domestic violence was rife back then, so of course it would be represented in their literature.

And there is no shortage of examples of abusive husbands in medieval literature. The twelfth-century Anglo-Norman story Yonec by Marie de France is a striking one: a lord marries a beautiful younger woman. He is afraid that she will be unfaithful, so he locks her up in his castle to assuage his jealousy. This causes her to sink into deep depression. She finds relief under the care of a mystery lover, but he is murdered by the violent husband.

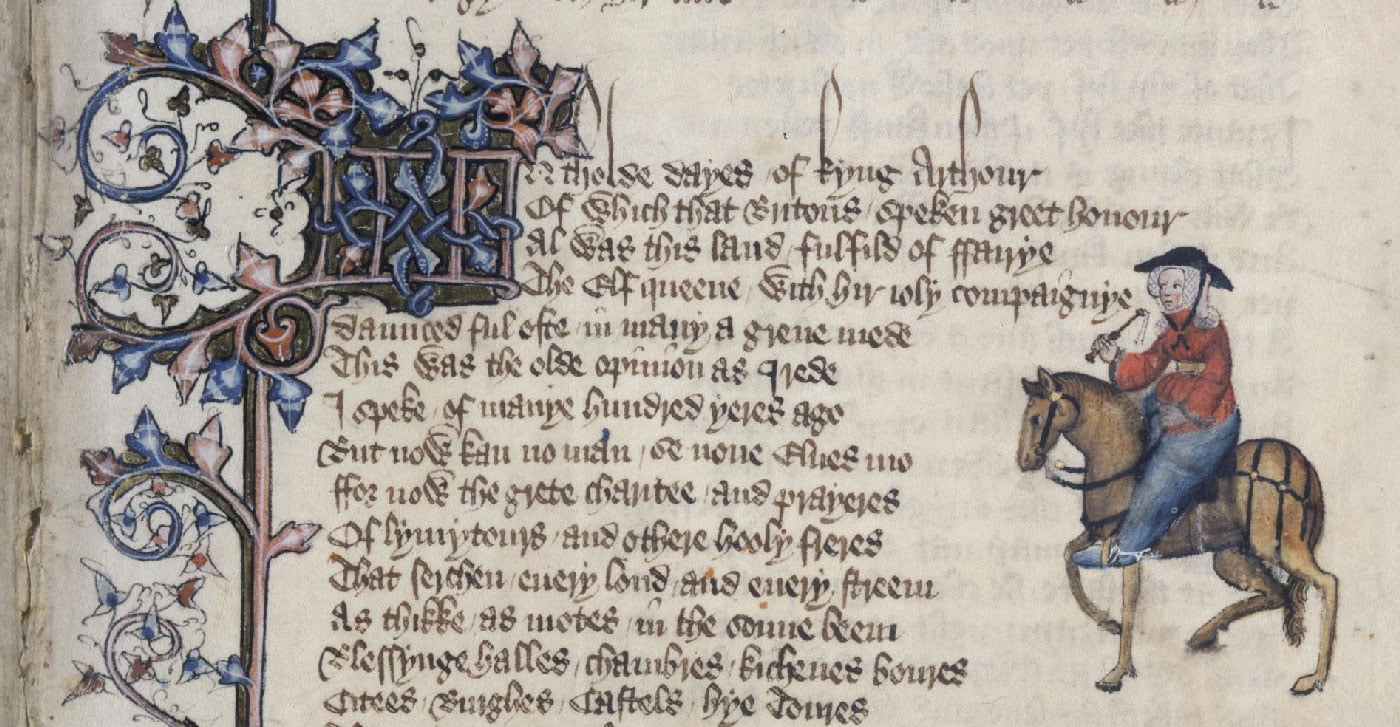

We also have the story of the Wife of Bath from Geoffrey Chaucer’s fourteenth-century English The Canterbury Tales, whose husband assaults her so badly he makes her partially deaf. Also in The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer spins a tale of Walter in “The Clerk’s Tale” (heavily influenced by Giovanni Boccaccio’s character Gualtieri). Walter, after marrying his lower-class wife, submits her to multiple cruel tests including allowing her to believe that he has killed their children. In twelfth-century France, Chrétien de Troyes wrote Erec and Enide. In it, Erec forces his wife to follow him silently on quest after quest when she dares to express concern about his reputation after their marriage.

And even when these husbands are not actively abusive, they can be negligent or abandon their wives altogether. You could even make a strong case for potential neglect by King Arthur towards Guinevere. In Arthurian literature, there is often very little interaction between husband and wife. In texts wherein the famous relationship between Lancelot and Guinevere is revealed to the king and he is forced to address the affair publicly, he is considerably more concerned about the loss of his best knight than he is about the loss of his wife – even when ordering that she be burned at the stake.

But I would like to counter the argument that medieval literature is uniquely rife with domestic abuse because the Middle Ages were an inherently abusive time towards women. If that’s true, then why does so much modern literature, from classics like The Color Purple to newer examples like Big Little Lies, also feature stories of abusers and abuse? The answer is that it happens frequently, then and now. We are maybe not as far removed from the medieval as we proclaim.

Marie de France and the Cycle of Abuse

To explore this, let’s look at the writings of one of the most famous female authors of the twelfth century, Marie de France. Historians don’t know much about the details of Marie’s life, although, from her name and some clues in her writing, we assume she was born in France and then moved to England. We do know that she was prolific and popular; her writing was almost certainly read in the court of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was, perhaps, the J.K. Rowling of her day.

Marie wrote medieval adventure stories known as “romances” (very different from what we think of as “romance novels” today). Medieval romances were developed by and for the nobility. They were produced by and for women in particular, who were patrons and readers of the genre.

At their core, medieval romances tended to center on knightly quests and courtly matters. They were often fantasy fulfillment for both male and female readers. Men dreamed of rich widows who could provide them with the land and fortune that they themselves would never inherit. And women might long for a lover who would rescue them from a less-than-desirable arranged marriage, or for a husband who would better care for them.

Marie de France’s romances don’t always have happy endings. In fact, several of her stories paint a very ugly picture of relationships between women and men. The abusive dynamics in them will immediately resonate with anyone who has experienced or studied the cycle of domestic violence.

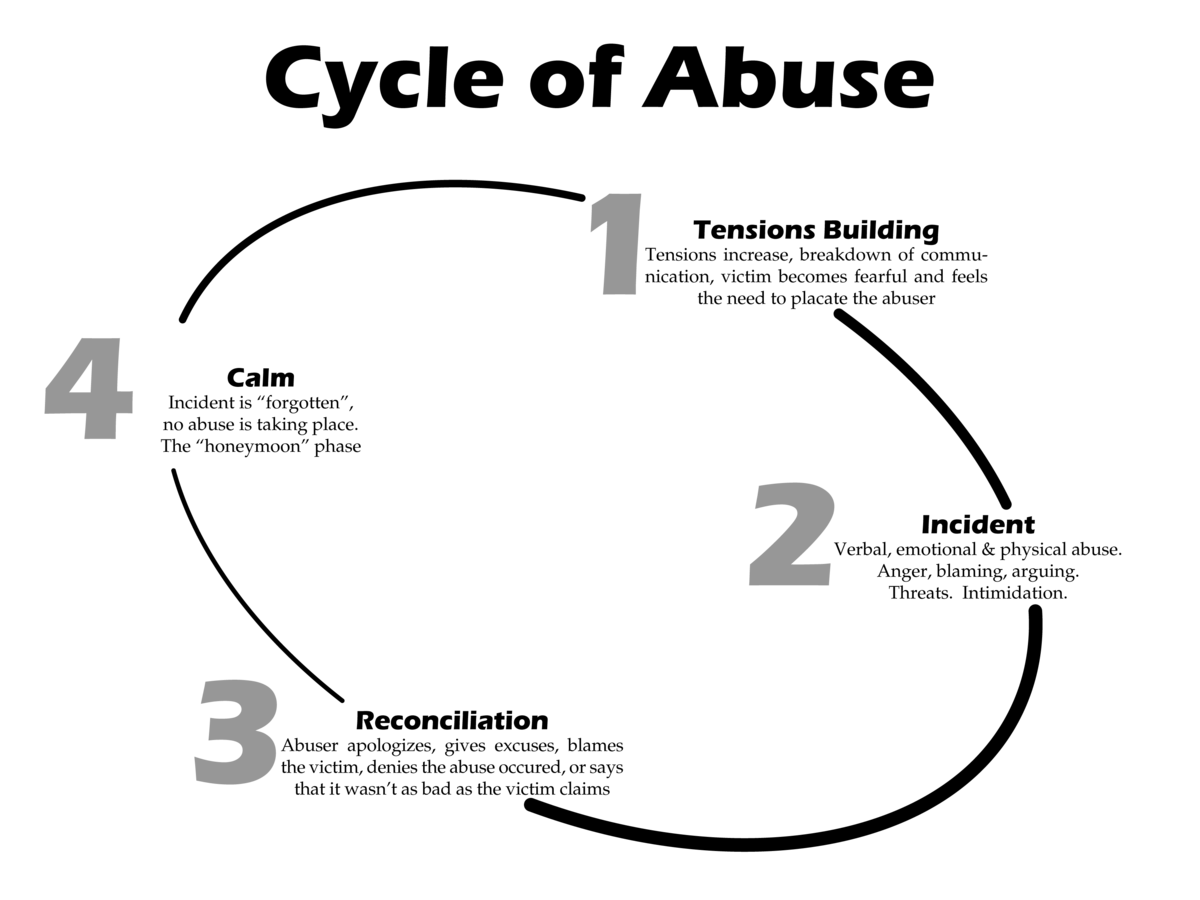

Described by Lenore Walker in The Battered Woman Syndrome, the cycle of violence begins with the “courtship period,” during which the abuser’s behavior presents as positive and loving. This is followed by three phases: tension-building, the abusive incident, and loving contrition. The “tension-building phase” is characterized by a change in behavior; the abuser might act sullen or angry. Victims describe this tension as “living on eggshells.” “Tension-building” leads up to the “abusive incident,” which can take many forms. The abusive incidents occur when the abuser acts on their fury, when the victim is no longer able to perform what Walker calls “anger reduction techniques” during the “tension-building phase.” The third phase mimics the “courtship period” and is accompanied by apologies and declarations. And the cycle begins again.

The Cases of Yonec and Bisclavret

We can find this very cycle in several of Marie’s works. I previously mentioned Marie de France’s Yonec and its clear depiction of domestic abuse. In that lady’s case, a shape-shifting knight appears to bring her the love and care she has been denied by her husband. The first part of the story, to the point that the knight shows up in her tower, is a portrayal of “tension-building,” during which the husband’s abusive behavior is evident: locking the lady up, causing her to change appearance due to depression, not allowing her to go to church, etc. When the husband finds out about his wife’s lover, he contrives to have the knight killed: “the abusive incident.” The wife expresses her desire to die as well, for her husband will, as she exclaims, kill her. The dying knight offers her protection by giving her a ring that will erase her husband’s memory, and the magic seems to work for the rest of her life: an extended “courtship period.” In this case, Marie closely follows the cycle of abuse structure.

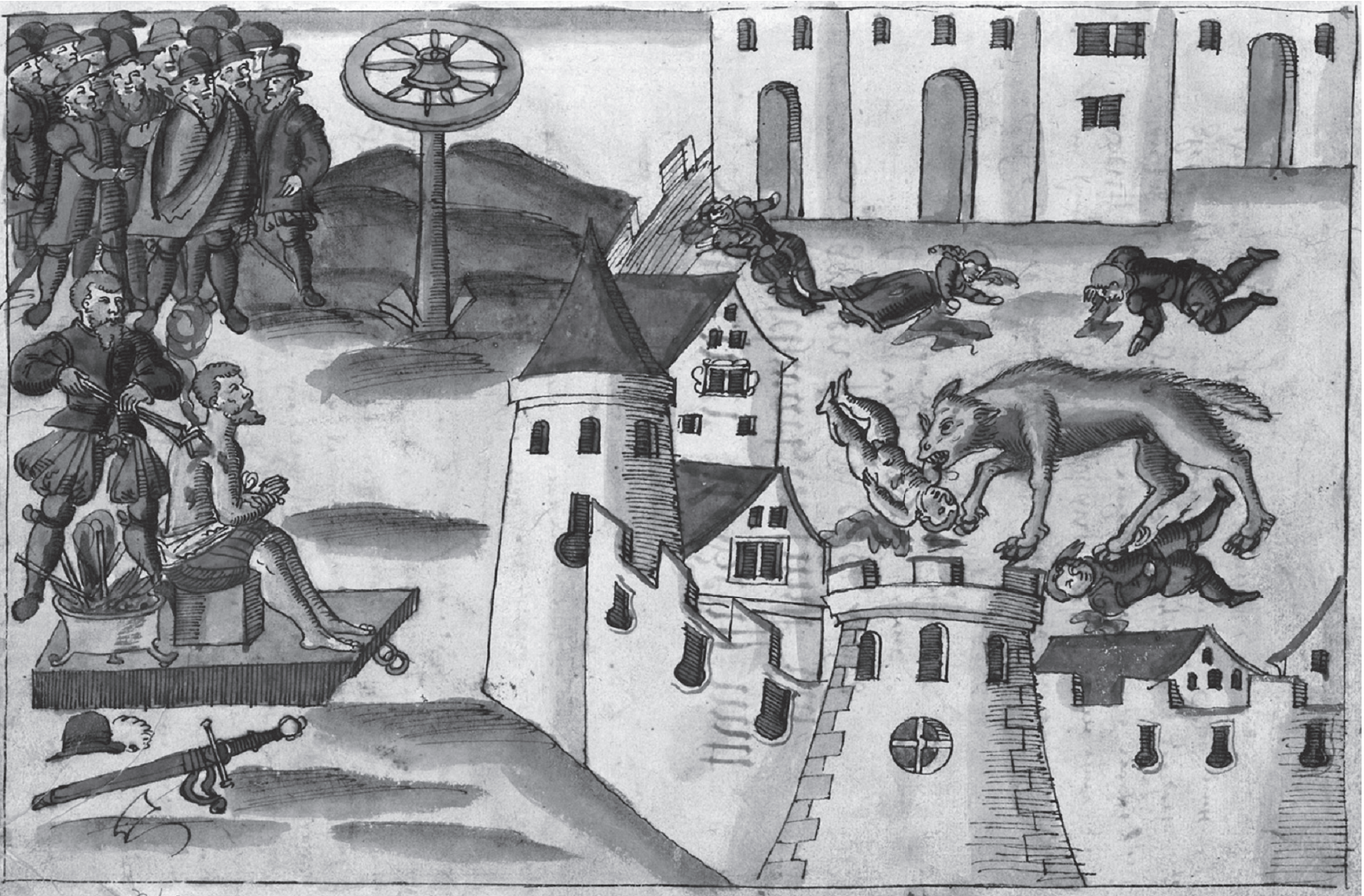

Another of Marie’s stories, Bisclavret, starts with a lord who is a werewolf. But he is a noble one—a harmless one who transforms a few days each month and who harms no one. Bisclavret’s wife, concerned about his absences, asks him repeatedly to tell her where he goes. When he does, she conspires with another knight to take the clothes that Bisclavret hides when he transforms—and which he needs in order to return to human form.

Trapped in wolf form, Bisclavret sees his king hunting in the forest. Displaying the ability to see nobility even in animals, the king takes the wolf into his court. When the wife visits the court, the wolf, who had not done any harm to anyone previously, attacks both the knight who stole his clothes and his former wife, tearing her nose off. At this point, the king, instead of blaming the wolf, takes the advice of his counselors and tortures the wife until she reveals what she has done. The clothes are recovered, and Bisclavret returns to human form. The wife is banished, and all of her daughters are born without noses.

In Bisclavret, the idea of abuse remains a hovering fear, rather than a defined reality. The moment the wife in Bisclavret decides to turn against her husband after learning he is a werewolf is often a point of confusion and discussion for readers. Are we meant to blame the wife? Given she later finds herself disfigured and tortured for her actions, it seems like a simple question. Nonetheless, as with everything medieval—and everything Marie de France wrote—the question is far more complex than it seems.

Unpacking Abuse

Imagine, for a moment, a medieval woman who grew up in the nobility. She is aware from an early age that she would be married to someone her family selected and approved. In Bisclavret, however, this wife marries someone described as “a handsome knight,” “an able man,” and “a noble man” (translations are from Judith Shoaf). Bullet: dodged.

Yet, there is a lingering issue: Bisclavret disappears. He keeps secrets. Where does Bisclavret go during his frequent absences? What could he be doing? The wife is understandably curious. Yet, when she confronts her husband, she does so with hesitation:

But I’m afraid that you’ll get angry,

And, more than anything, that scares me

What scares her “more than anything” is that her husband will “get angry.” Why? Bisclavret has given no indication to his wife that he would be violent towards her before this. She has no evidence for her fear—Bisclavret does not give us the same situation as Yonec in which the wife has clear reason to hate and fear her husband. And, yet, Bisclavret’s wife demonstrates the same fear. Could her statement indicate a lingering anxiety about how her husband will treat her? Has she heard stories of men—such as the husband in Yonec or Chaucer’s Walter—who were abusive to their wives? What had her mother, her friends, or her female relatives told her?

When Bisclavret finally tells his wife about his shape-shifting, his revelation is certainly not what she expected (it’s entirely possible that she believed he was involved with another woman). Her reaction is intense:

The lady heard this marvel, this wonder.

In terror she blushed all bright red,

Filled with fear by this adventure.

Often and often passed through her head

Plans to get right out, escape, for

She didn’t want ever to share his bed.

We can chalk up her fear to the prospect of being married to a werewolf. The text does ask us to grapple with what our own choice would be in this situation (and it is indeed a good question to ponder). But how the wife’s reaction is described is familiar to anyone who has been a domestic abuse victim, who has known one, or who has read about one. She “often and often” has thoughts of escape “pass through her head,” and she is “filled with fear.”

Inner Beasts

Bisclavret’s wife no doubt has the same information that we the readers are given by the narrator at the very beginning of the text:

A garwolf [werewolf] is a savage beast,

While the fury’s on it, at least:

Eats men, wreaks evil, does no good,

Living and roaming in the deep wood.

An illustration from Topographia Hiberniae depicting the story of a traveling priest who meets and communes a pair of good werewolves from the kingdom of Ossory, Ireland.

Royal MS 13 B VIII, ff 1r-34v.

Bisclavret, we are told, is not a typical werewolf. Marie de France takes great pains to tell us immediately that he is not one of those savage beasts who eat men. At this time in medieval Europe, while there are some positive versions of lycanthropy, there are uses of the werewolf trope in literature as a punishment for a misdeed or sin—think, perhaps, of the Beast from Beauty and the Beast. In the Early Modern period, werewolves were associated with witches. All in all, being a werewolf was not just bad news, but could be an indicator that you were a bad person.

If the werewolf is a metaphor for evil men in general, it’s certainly an even better one for abusers specifically. Werewolves are described as savage when “the fury” is on them “at least,” which matches the “tension-building phrase” turning into the “abusive incident.” Marie adds the “at least,” not just for the sake of the rhyme, but to indicate that these creatures can be violent even when they are not in their lupine form. The phenomenon of “were-abusers” transforming from seeming kindness to exhibiting bursts of violence and back again is well-documented, appearing frequently in victim narratives.

The wife states that Bisclavret’s anger scares her more than anything, and then she discovers that her husband transforms into a creature traditionally known for its violent rages. The very things she was conditioned to fear have become, in her mind, a reality.

That Bisclavret is not an abusive husband is not the point. The wife has heard the stories. She knows abusive relationships. And she is convinced that she is in one—or about to be. These circumstances are what fuel her actions.

So, we are left with a very difficult question: what is ethical for a victim of domestic violence to do in order to escape their abuser?

“Why Doesn’t She Just Leave?”

This question appears over and over again in the lives of abuse victims. The story of Janay Palmer, wife of NFL player Ray Rice who was videoed being assaulted by her then-fiancée is a prime example. It spurred the #WhyIStayed hashtag in 2014. This movement endeavored to combat the all-too-popular belief that, if a woman stays with a man, then she must not be truly abused.

Masefako Gumani and Pilot Mudhovozi, in their article “Gender-based Violence: Opportunities and Coping Resources for Women in Abusive Unions,” list several reasons why abuse victims stay in abusive relationships, reasons that are echoed in many studies on the subject. Among these are:

- socialized to stay in relationships,

- belief partner will reform,

- lack of social and financial support, including “the uncertain future of poverty, inadequate housing and social isolation,”

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and

- the terror of leaving given that so much of reported domestic abuse happens when women try to leave.

The idea that these women feel they have nowhere to go is particularly poignant for women like the wives in Yonec and Bisclavret.

In Yonec, the wife, locked as she is in her tower, does not attempt to leave until her lover is mortally wounded. When this happens, she jumps out the window to follow his trail of blood back to his own kingdom.

You might ask, “Why didn’t she leave until then?” But the wife mentions in an earlier soliloquy that her family gave her away to her husband. She even curses them for doing so. So where would she go? When she jumps out the window, Marie tells us “it’s a miracle she’s not killed” as it is so high. That the wife attempts it at all is testament to her fright, grief, and bravery.

Bisclavret’s wife chooses a different route. She turns to the one support she feels she has, a neighboring knight who had often professed his love for her. Marie is clear:

She had never loved him before this,

Nor let him think her love was his

Telling him about her husband and promising her love in return, she convinces him to steal Bisclavret’s clothes, preventing his return to human form. There is no question: this is an act of betrayal. Bisclavret does not deserve this. But, it is what she clearly felt she needed to do to prevent the abuse she saw in the future. If her fears had proven true, would we blame her?

A Culture of Violence

Marie de France asks us to consider what might happen in a situation where a woman, dreading the possibility that her husband would abuse her, believes that fear has come true. Her heightened anxiety at the beginning of the story leads to actual violence against her at the end. Yes, she does seek to imprison a good man. But the consequences of this are Marie’s thought-experiment about the tragic effects of repeated violence against women. Rather than a commentary on women’s betrayal, it is a commentary on the fear that is a natural side effect of a culture of violence.

Domestic Violence includes “physical violence, sexual violence, psychological violence, and emotional abuse [although recently that definition is inexplicably being challenged by the current presidential administration]. The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other.” The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV) reports that:

- On average, nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in the United States. During one year, this equates to more than 10 million women and men.

- 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have been victims of [some form of] physical violence by an intimate partner within their lifetime.

- 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men have been victims of severe physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

The Stop Street Harassments nonprofit found in a survey deployed in January 2018 that “81 percent of women and 43 percent of men had experienced some form of sexual harassment during their lifetime.” The #MeToo movement has revealed the extent to which women experience violence—and thus the extent to which women hear the stories about violence. Memes of every kind flood our social media, often accompanied with “advice” on how women can “avoid” such situations, advice that increases the fear that they will happen.

There is incredible danger in living in a culture that permits and even promotes violence, abuse, and rape. Being victimized is obviously traumatic. But there is an additional trauma too. There is further trauma for women, medieval and modern, in knowing that the chances of becoming a statistic are mind-blowingly high. Telling and reading the stories helps to keep the wolves at bay.

Resources for Domestic Violence Survivors

National Domestic Violence Hotline

National Coalition against Domestic Violence

Pathways to Safety International

National Sexual Assault Hotline

National Organization for Victim Assistance

Want to Learn More?

Rose, Christine, and Elizabeth Robertson, eds. Representing Rape in Medieval and Early Modern Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Salisbury, Eve, Georgiana Donavin, and Merrall Llewelyn Price, eds. Domestic Violence in Medieval Texts. University Press of Florida, 2002.

Skinner, Patricia. Living with Disfigurement in Early Medieval Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.