This is Part 12 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Linnea Hartsuyker. You can find the rest of the series here.

Over the past generation, more and more people have spoken publicly about how their experience of gender does not fit into a strict binary—masculine or feminine. Their expression of their gender may change between or away from those binary options. They may have fluidity or neutrality in their gender that changes over time—with periods of stability and periods of flexibility. Or they may outright reject any demand to choose between two artificially constructed, rigid gender poles. Many describe themselves as “non-binary,” “genderqueer,” “gender fluid,” or “gender non-conforming.” For example, actor and star of films like Justice League and Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Ezra Miller recently came out as proudly non-binary.

Some people think of gender fluidity as something new, a concept invented by the LGBTQ movement in the late 20th century, but humans have been pushing and questioning the boundaries of gender expression since the dawn of history. Those who argue that men and women are meant to take mutually exclusive roles in society sometimes point to the medieval past as a time of “natural” gender identity, when men were men, women were women, and no one ever blurred those lines. People who are attached to rigid gender roles also often have a particular crush on the Vikings because of how straightforwardly butch they have been made to seem in our popular culture.

Viking traditions, religion, and laws did promote separate spheres for men and women. Effeminacy was frowned upon: a woman could divorce her husband if he wore women’s clothing. Some people even believed that a woman’s touch could render men’s weapons ineffective. Vikings had words for sexual contact between men, and it was considered shameful for a man to be the receptive partner—in that case he was called ergi. A man labeled an ergi could demand blood or payment in recompense for the “insult.”

Still, traditional Viking gender roles were different from modern conservative ideas about them. For instance, although Viking men usually wielded weapons and Viking women typically managed the homestead, women were not homemakers in the modern sense. Viking homesteads were often large farms that employed and housed hundreds of people; the women who ran them were more like a modern CEO than a 1950s housewife.

Viking art, archeology, and literature also show plenty of evidence that both men and women in the Viking world defied common gender stereotypes. They bravely lived their lives despite the social stigma that they faced, like so many people do today.

Gender-Bending Viking Gods

Even the Norse gods were pretty genderqueer folx sometimes. Loki, the Norse god of mischief, is the best-known gender-bender of the Norse pantheon. He is a shape-changer who can alter his sex, and whose unbridled sexuality is a force for chaos for both his friends and enemies. He famously transforms into a mare to seduce away a stallion that is helping a frost giant build the wall around Asgard, and, as we are told in the Prose Edda,

…Loki’s relations with Svadilfari [the stallion] were such that a while later he gave birth to a colt.

That colt was Sleipnir, Odin’s eight-legged horse.

But Loki is not the only gender-bending Norse god. In another episode, recorded in the Poetic Edda by Snorri Sturluson, Thor decides to dress, and successfully pass, as a woman when his hammer is stolen.

To get it back, Thor and Loki make an expedition to Jotunheim. The giant that has stolen Thor’s hammer—without which he cannot protect Asgard—has demanded as a ransom the goddess Freya’s hand in marriage as well as the sun and moon. Loki suggests that Thor dress as a bride and pretend to be Freya to gain access to the giant’s stronghold and take back his hammer. But Thor is concerned about how this will reflect on his manhood:

Heimdall, the fairest of the gods, like all the Vanir, could see into the future. “Let us dress Thor in bridal linen,” he said, “and let him wear the necklace of the Brisings. Tie housewife’s keys about his waist, and pin bridal jewels upon his breast. Let him wear women’s clothes, with a dainty hood on his head.”

The Thunderer, mightiest of gods, replied, “The gods will call me womanish if I put on bridal linen.”

As part of the wedding ceremony, Loki asks the giants to lay Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir, in his lap to sanctify the union.

Then Thrym, the lord of giants, said, “Bring me the hammer to bless the bride. Lay Mjöllnir on the maiden’s lap, let the two of us thus be hallowed in the name of Vor, goddess of vows!”

This was a common blessing; either at a wedding or a son’s naming, a sword or other weapon would be laid across a woman’s lap as a phallic fertility symbol. As a fertility god (Thor brought storms and rain), in this false wedding, he is both bride and groom.

Thor’s cross-dressing is done for comic effect, but has a good outcome for him and Asgard: he retrieves his hammer and can again defend the gods. Its humor comes from the fact that Thor is the most representative of masculine virtues and the hardest god to disguise—it is a comment on the stupidity of the giants that they don’t see through the ruse. At the end, Thor’s masculinity is undiminished and he defeats the frost giants with his restored hammer. Still, this tale also shows some room for play within the rigid requirements of masculinity and femininity in the Viking Age.

The Alfather’s Use of Women’s Magic

If Thor’s cross-dressing smacks of the comical, Odin’s journeys into women’s spheres are not so easily dismissed. Odin the Alfather, the chief of the Norse gods, was the god of war, magic, wisdom, and ecstatic states. While roughly the same number of women and men performed magic in the Old Norse sources, women use magic more often. And more, those men who performed certain kinds of magic were considered dishonored as though they were ergi—a receptive homosexual partner.

Seiðr is a form of magic specifically practiced by women. It is associated with the goddess Freya and with the völva—a seeress and sorceress who narrates some of the tales recorded in the Eddas. Seiðr is interpreted by Professor John McKinnell to mean the action of “sitting out” and in practice described the magic-worker sitting out all night to raise and control the spirits of the dead. The practitioner would, allegedly, go into a trance and have seizures through which the dead would speak.

However, the Ynglinga Saga tells us that Freya taught seiðr to Odin, who used it to gain knowledge of the future. Odin was a male god of berserkers and also of the out-of-body ecstasy usually associated with women’s magic. He displays shamanistic characteristics through his journeys to various otherworlds in search of this wisdom. As the popular meme goes, “Get you a man who can do both.”

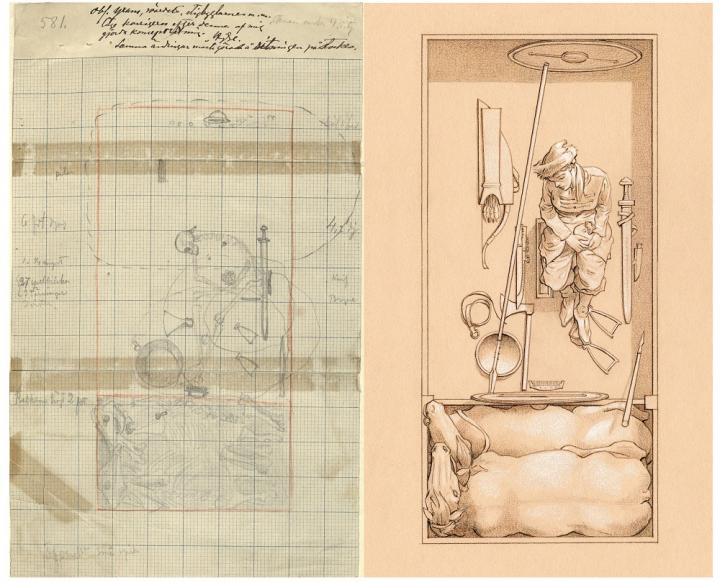

Archaeological finds also shows us how Odin’s gender was blurred. This seated figure was found in Denmark, and dated to the 10th century:

Odin from Lejre. Image by Mogens Engelund, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Despite its small size (less than an inch square) it is very finely detailed. The figure wears women’s attire: a long gown with an apron, a cloak, and a string of beads, but it also has only one eye and sits with two ravens behind it, symbols of Odin. What precisely this figurine is depicting is open for interpretation, but it is unquestionably a blending of masculine and feminine symbols in the same person.

Odin was a magician and seer, god of battle and god of the dead. He was dogged in his pursuit of wisdom, which including communing with the dead, elsewhere described as women’s magic. Like Thor, he embodied masculine warrior virtues. Also like Thor, his security in his masculinity allowed him to take on women’s roles from time to time, and even gain power from doing so, without losing his honor.

Women in Men’s Worlds

In many ways it was easier for Viking women to cross gender lines. Since men were considered “superior,” it was deemed only natural that a woman might covert to a man’s roles. The image of the Viking woman warrior is a popular one; Lagertha from the hit show Vikings is only the latest iteration of our obsession with them. Most scholars, though, believe that if women warriors existed, they were rare—women in unique circumstances cut off from the social structures that usually protected or bound them.

In 2017, a Viking skeleton originally unearthed in the 19th century was re-examined using DNA analysis, and the results caused a bit of a firestorm in the media. This is because the grave of a Viking warrior—identified by the grave-goods (meaning, the objects buried with a person) found there—were similar to those found in other warrior graves; things like a sword and a game board.

But the skeleton, as they discovered in 2017, was genetically female.

This was quickly hailed as a fabled “Viking warrior woman” in the media. But while this “Viking warrior woman’s grave” was certainly the grave of a high status woman, but the evidence that she actually wielded the weapons she was buried with is tenuous at best. The sword found in her grave may have been symbolic, since women often held swords in trust for their sons. And the presence of a game board probably supports the idea that she played the game, but that alone does not make her a warrior.

Where weapon-wielding women exist in Norse literature, they appear to be a very conscious literary trope, showing a society or situation out of balance that will be put back into balance by a man. Thordis, a female character in Gísla’s Saga, spends most of the tale counselling the men around her to take revenge on those who wronged them. After it occurs, she experiences remorse and attempts to stab one of the perpetrators in the leg. But, she is not skilled enough with a sword and botches her attack:

…as she stoops after the spoons she caught hold of the sword by the hilt and makes a stab at Eyjolf, and wished to run him through the middle, but she did not reckon that the hilt pointed up and caught the table; so she thrust lower than she would, and bit him on the thigh, and gave him a great wound.

She then divorces her husband and goes to live by the shore, physically and symbolically on the outskirts of society.

Few sources show women taking up weapons without negative consequences, but women did take on other men’s roles more successfully. Skaldic poetry was a regimented type of Norse court poetry that employed poetic alliterations, strict meter, and allusive kennings (for example calling a battle a “crow’s feast”, or the sea the “swan’s road”). It was considered a masculine art, recited by men, about men. But the verses of four women skalds are recorded in medieval Icelandic writings as well. These are part of larger prose narratives, and also concern themselves with battles and sea voyages. However, they often have an ironic edge, like the woman skald Steinunn who composed a verse about a man who embarked on a great sea voyage but never left the harbor:

Thor altered the course of Thangbrand’s

Long horse of Thvinnill, he tossed

And bashed the plank of the prow and smashed

It all down on the solid ground;

Hilda Hrolfsdatter was a noblewoman who acts as a skald in the saga Heimskringla. She begs for her son not to be outlawed, while using the tropes of skaldic verse:

Bethink thee, monarch, it is ill

With such a wolf at wolf to play,

Who, driven to the wild woods away

May make the king’s best deer his prey.

The fact that these women’s verse was included in literature composed by men shows that skaldic verse was a realm that women could and did step into.

Another way that some women could enter masculine spheres was, frankly, by growing old and wealthy. Viking widows kept their dowries and did not fall under the control of their younger male relatives as Christian women so often did. As such, they enjoyed great independence. Women in the Icelandic sagas are often praised for qualities elsewhere only associated with men, like being “valiant” and “forceful”. Older women past their childbearing age no longer inspired sexual jealousy among men, and unlike aging warriors, they were not scorned for losing prowess with weapons. In some ways, this was the best of both worlds.

Runic texts (which were inscriptions chiseled on rune-stones commissioned and erected during the Viking Age) bear witness to powerful widows as well. One of the older rune-stones found near Alstad, Denmark bears an inscription which says that it was commissioned by a woman in honor of her dead husband. The text also states that the stone, which is 3 meters tall, came from an island 100km away, and was transported to Alstad across mountainous terrain. The inscription says that

Jorunn raised this stone after [her husband] who had her to wife and [she] brought it [i.e. the stone] from Ringerike, out of Ulvoya and the stone will honor them both.

Clearly this woman was both wealthy and influential, and wanted those qualities to be known.

Gender Rules are Made to be Broken

Gender expression has never been as static or natural as some modern-day social conservatives would have us believe, even in a society that prized masculine virtues as much as the Vikings did. Throughout history, and in every culture, women and men have stepped outside of the boundaries that society draws around them. Sometimes they needed great personal power to avoid punishment for doing so, as in the cases of gods and wealthy widows. But gender roles have always been mutable, even in the most traditionally masculine societies. After all, the fact societies have always put energy into policing gender roles, means that they are not natural—if they were no laws or mores would be needed to enforce them.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.