This is part 2 of The Public Medievalist‘s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Yvonne Seale. You can find the rest of our series here.

“Lady” is a simple word. But it can be used to mean very different things. It’s a standard way to refer to a woman; it is often used to confer a measure of social approval. But it’s got a broad range of meanings. “Lady” can imply an aristocratic title and tiara. Or, it can be used to describe someone who scrubs toilets for a living (a “cleaning lady”).

The word can coyly refer to a romantic partner (“my lady friend”) or to a sex worker (“a lady of the night”). It was one of my late grandmother’s highest compliments (“she has beautiful manners; she’s a real lady.”) But the word had very different connotations during the Middle Ages, connotations that we have to be aware of when we think about the distant past and how it relates to the present.

Why Medieval Whiteness Matters

One of those connotations concerns race. I’ve been thinking a lot about the word “lady” in light of a roundtable discussion on medieval religion that I attended at the International Medieval Congress at the University of Leeds. One of the panelists urged that medievalists be more mindful of the ways in which they assume “whiteness” and “Christianity” to be neutral defaults. This got some pushback in the question-and-answer session; it’s all well and good to acknowledge race from a theoretical perspective, one commenter said. But what practical use is it to talk about black people if you study thirteenth-century Bohemia?

This logical leap is one that crops up in many contexts when people think and talk about the Middle Ages—a jump from a simple reminder that “modern ideas about race shape how we view the distant past” to “there is no need to think about race and the Middle Ages because there were no black people in medieval Bohemia.”—which is, in itself, not necessarily true.

Talking about race and the Middle Ages is often framed as impractical or irrelevant—but it’s only possible to do so if you ignore the fact that “white” is a racial category in itself. Whiteness shapes how white people—whether scholars or otherwise—view the past. As film studies scholar Richard Dyer noted in his book White (1997),

as long as race is something only applied to non-white peoples, as long as white people are not racially seen and named, they/we function as a human norm. Other people are raced, we are just people.

Despite decades of activism and increasingly vocal protest about racial injustice, there’s still little push for white people to think about how their race shapes their daily lives. White people are rarely required to think about how their whiteness informs their view of history—although, of course, it does. Popular understandings of the Middle Ages in particular are still grounded in nineteenth- and early-twentieth century research, research that was invested in valorising whiteness.

The “Disneyfication” of the Medieval Lady

One of the ways in which we can see this most clearly is to look at the idea of the “lady.” After all, the lady—and one of her sub-categories, the “damsel in distress”—is a stock character in the modern imagination of the Middle Ages. Medieval ladies in the popular imagination are marked out by their physical appearance (pretty, slender, white, usually blonde) and their passivity. They wear flowing gowns and elaborate headgear.

As a brief aside, the cone-shaped hennin hat that has become a visual shorthand for “medieval princess” was only worn in Europe at the very end of the Middle Ages. This symbol of white femininity may well have originated in Asia as a fashion among Mongol princesses, and been brought back west with by Marco Polo.

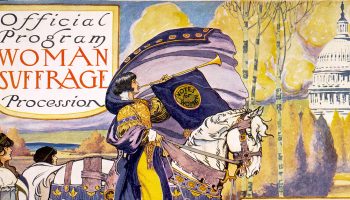

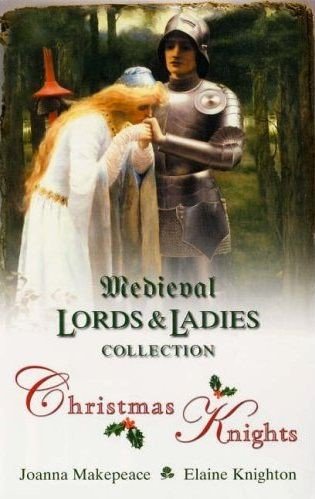

This image of white aristocratic femininity is reproduced over and over again in modern depictions of the Middle Ages. For example, there’s a whole genre of romance novels that slap images like this on the cover, a quick way of advertising the content within: a medieval heroine who is usually virginal and upper class, and a rescuing hero who is a “chivalrous,” romanticised knight. The blurbs of these books talk about “hot-blooded warriors” and “courtly lovers,” about women who are helpless to refuse the honourable “protector” who has “the power of life and death over [their] family.” In a similar vein, Disney animated movies— from Snow White (1937) to Tangled (2010)— feature “Princess” heroines who inhabit generic medievalesque landscapes, and whose virtuous purity is rewarded with a heterosexual love interest and a “happily-ever-after” ending. As scholar Clare Bradford points out, no matter how spirited these heroines are, they can’t escape the “hazy romanticism” of Disney’s “modern medievalism.”

True, some books and movies try to subvert these tropes. Modern fantasy novels set in a quasi-medieval Europe often conjure up gritty worlds with a “general condition of female disenfranchisement” in order to make their female protagonists stand out: think of Eowyn in The Lord of the Rings, or the woman of your choice in A Song of Ice and Fire (or its HBO adaptation Game of Thrones). They’re not like those other princesses—they’re tough, and muddy. They’re oppressed, but they’re defiant. It’s difficult to get away from the dominant pop culture ideas. The live-action Disney movie Enchanted (2007) was a successful satire of traditional Disney tropes about princesses, but it only worked because of how familiar and compelling those tropes are.

The Long Shadow of the Victorians

The ideas that animate Harlequin romance novels, Game of Thrones, and Disney movies alike can be traced back to the nineteenth century. Look at the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites and others influenced by them—works like John William Waterhouse’s “Lady of Shalott” (1888) and Frederic William Burton’s “The Meeting on the Turret Stairs” (1864)—and you’ll see some very familiar figures. These canvases reflect popular Victorian understandings of medieval ladies: passive, slender, aristocratic, the objects of knightly devotion. These women have never laboured in the fields with sunburned necks or callused hands. Their clothing and flowing hairstyles are eclectic, designed more to make nineteenth-century audiences think about a distant, misty, heroic past than to accurately reproduce any given moment in the Middle Ages. And, they are, invariably, white.

Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. These paintings were produced when European imperialism was at its zenith; when Darwinian theories of evolution were twisted to justify colonialism and social hierarchies based on race; and when a supposed early-medieval “Teutonic”—or Germanic—ancestry for the white Protestant populations of Britain and North America was claimed to be the reason for the explosive economic growth of those regions. They were also painted at the same time that white people in Europe and the Americas were enjoying steadily increasing standards of living—in large part thanks to the backbreaking, and often coerced, labour of those in colonised places. Black and brown women helped to shape history, but Victorian society excluded them from the category of “lady” because of the colour of their skin.

Nineteenth-century thinkers drew on the medieval past in order to justify racial and class inequities, or burgeoning notions of nationalism. These thinkers racialised the medieval lady. They idealised her as white, passive, and unsuited to manual labour. In doing so, they made her into a rationale as to why her elite, white, female descendants could sip tea in parlours while brown and black women toiled in the fields—or in their houses—to bring them that tea. The status quo was given such a venerable heritage that it was made to seem natural, even inevitable. Such ideas were then, and are now, pervasive and insidious. They were absorbed by white women, by Disney animators, by the makers of Halloween costumes, and even by those who write histories.

But what happens if we take the medieval lady off her pedestal? What kind of woman do we see inhabiting the Middle Ages if we try to peel off the Victorian veneer of chivalry and politesse? Does looking at what medieval people actually did in the past tell us something about our own assumptions concerning race and gender? In part, this is a process where we have to reconsider the language we use. What do we mean by “lady”? What did medieval people mean by the term? Or, rather, since most texts produced in western Europe in the Middle Ages were written in Latin, what were the connotations which they associated with the word domina?

Making a “Lady”

The first key difference is that the modern English word “lady” simply doesn’t have the aura of power which the Latin word domina did in the Middle Ages. A domina was a woman with authority and moral rectitude in her own right, not simply the consort or complement to a dominus (lord). A domina (and holders of other Latin titles applied to women in medieval records, like comitissa, vicedomina or legedocta) administered estates and adjudicated legal disputes. It did not matter whether she held her title by inheritance or through marriage. Those who held titles in their own right, or those who were widowed, could exercise significant power over fiefs and vassals.

For example, when Matilda, countess of Tuscany (1046-1115), was referred to as domina, it was because she controlled a large swathe of northern Italy. She was the mediator during the famous meeting between Pope Gregory VII and the German emperor Henry IV at her great fortress of Canossa. In doing so, she influenced the outcome of a major medieval power struggle. On his accession to the throne in 1199, King John of England installed his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine (ca. 1122-1204), as domina of the French territory of Poitou and gave her authority in all of his lands—a tacit acknowledgement of her political skill. Eleanor even managed to expand queenly authority in some ways. She seems to be the first queen of England after the Norman Conquest to have regularly collected the “queen’s gold”, a one-tenth share of some of the legal fines paid to the king. This gave her a valuable (and somewhat independent) source of revenue—and with money comes power. As a more modest example, one contemporary of Matilda of Tuscany’s was a woman named Mahild of Alluyes, domina of a far smaller territory in northern France. She wasn’t a player in papal or imperial politics. Yet as wife and widow, she oversaw the affairs of her vassals and witnessed charters which they drew up in the chapter house of the nearby abbey of Marmoutier, which gave her considerable influence over their lives. And there are many, many more dominae in the sources.

Medieval aristocratic women were sometimes seen as passive by their male contemporaries; those with power who broke this mould were sometimes described in plainly misogynistic terms. But equally, their deeds could be lauded. For example, one of the great chroniclers of the early twelfth century, the Anglo-Norman Orderic Vitalis, wrote that the French noblewoman Isabel of Conches was “lovable and estimable to those around her.” He complimentarily said that she “rode armed as a knight among the knights”, and compared her favourably with Amazon queens. Matilda of Boulogne (ca. 1105-1152), queen of King Stephen of England, was one of her husband’s most capable partisans during the Anarchy—the period of civil war that tore twelfth-century England apart. Not only did she head the government during her husband’s captivity, but proved herself a capable military commander. She directed troops into battle at the so-called Rout of Winchester and arranged for her husband’s release when he was captured. A generation or so later, the English countess Petronella of Leicester (ca. 1145-1212) participated alongside her husband in the Revolt of 1173-74; she gave her husband military advice, rode armed onto the battlefield, and was even wearing armour when captured. These actions may not have been normal behaviour for a domina—administration and adjudication were more usual. But they were still within the bounds of possible behaviour for a medieval woman without endangering her status as a “lady.”

The Matildas, Mahild, Eleanor, Isabel, and Petronella: it is hard to imagine any of these dominae as the subject of a Waterhouse painting or the centrepiece of a Disney movie. They weren’t always victorious or virtuous; they could be ambitious and high-handed and hold ideas which most people today would find distasteful. And yet, whether medieval chroniclers approved or disapproved of these women individually, they didn’t think the very fact that they were active, decisive, and opinionated was out of the ordinary. Neither should you.

Rethinking Our Assumptions

Nor would the colour of their skin have been thought a defining aspect of their status as a lady. There was certainly prejudice about skin colour in the Middle Ages. The relatively small number of non-white people in northern Europe means that we can’t definitively point to a woman of colour exercising political power there. But things were slightly different in southern Europe, in areas like Iberia—modern Spain and Portugal—which was long home to Christian, Jewish, and Muslim populations of multi-ethnic heritage. While there were religious prohibitions against Muslim women marrying non-Muslim men, there are some scattered examples of intermarriages between dynasties in the early Middle Ages: Muslim women of north African or Arab descent marrying into northern, Christian royal families. For instance, Uriyah, a daughter of the prominent Banū Qasī dynasty, married a son of the king of the northern Spanish kingdom of Navarre; Fruela II, king of Asturias, married another Banū Qasī woman called Urraca. Their ancestry doesn’t seem to have posed a barrier.

Western Europeans may have only rarely had direct contact with non-white female rulers further afield—like the powerful Arwa bint Asma, queen of Yemen (r. 1067-1138)—but when they did, it could be in dramatic fashion. Shajar al-Durr, sultana of Egypt (d. 1257), famously captured Louis IX of France during the Seventh Crusade and ransomed him for an eye-wateringly large sum.

While historical examples of women of colour exercising prominent roles in Europe during the Middle Ages are few in number, skin colour didn’t limit the imaginations of white medieval Europeans. Medieval people often had clear anxieties about skin colour and blackness, but despite this racism they could still envision a brown- or black-skinned woman as a member of the upper classes, just as they did the white-skinned Mahild or Isabel. For example, the early thirteenth-century German epic poem Parzival centres on the eponymous hero and his quest for the Holy Grail. Parzival has a half-brother, the knight Feirefiz, who is mixed-race. His mother, Belacane, is the black queen of the fictional African kingdoms of Zazamanc and Azagouc; the narrative praises her beauty and her regal bearing. As another example, a Middle Dutch poem written about the same time, Morien, recounts the story of the handsome, noble knight Morien, “black of face and of limb,” whose father Sir Aglovale fell in love with his “lady mother,” a Moorish princess.

However, the most vivid example is provided by medieval depictions of the biblical Queen of Sheba. Scholars think the historical Sheba likely lay somewhere in southwestern Arabia; other traditions place the kingdom in east Africa. Regardless of the queen’s historicity, various traditions grew up around her in the Middle Ages. Some of the most popular of these claimed that she had a son by the biblical king Solomon. She frequently appears alongside him in art, in elegantly draped garb as on the late twelfth-century Verdun Altar, or accompanied by courtiers as in an early fourteenth-century German illustrated bible: a beautiful black woman and a regal queen. When you think of a medieval “lady”—you could do worse than to think of her.

What Lady Should Mean

All of this should prompt us to look again, to reconsider how racialized Victorian ideals of womanhood still impact us—both in contemporary popular culture and also in our understandings of the medieval past. When we think about the Middle Ages, we should consider the impact of race, and especially whiteness, on how we think about it. That is not necessarily because our medieval forebears did so, but because our nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ones did so very much.

The idea of the “lady” was one of the useful fictions which they and others employed, glorifying white, upper-class womanhood as an apex of western achievement. This helped to make existing racial and imperial hierarchies seem like they had such a long history that they must be innate, biological: a simple fact of life. But it was a fiction, and a harmful one. If we are to better understand the medieval past, it is one we must set aside.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.