This is Part 16 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Kit Heyam. You can find the rest of the series here.

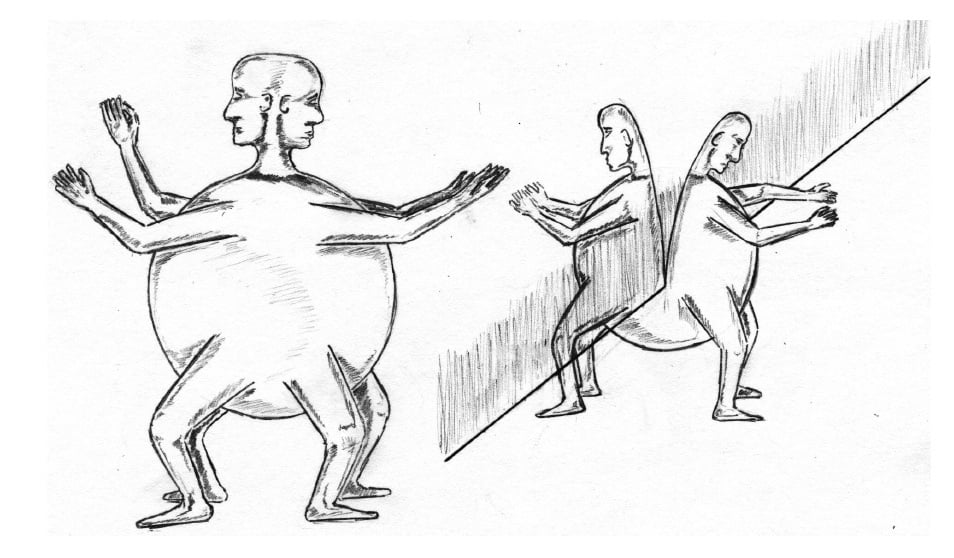

When you look at the picture on this bowl, what do you see? Is it two people in a close—but slightly uncomfortable-looking—embrace? Is it a pair of conjoined twins? Is it a fantastical creature with two heads, two arms and four legs? Or is it something else?

In the early 1930s, Sir Leigh Ashton—then director of London’s Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, where this bowl is currently on display—knew what he saw. The museum had been offered the bowl by an antiques dealer, and Ashton was keen to acquire it. He wrote enthusiastically to the V&A’s ceramics curator Bernard Rackham, describing the bowl as

a fine example of a late Byzantine bowl with sgraffito design of a hermaphrodite, probably from Cyprus.

In seeing the figure (or figures) on this bowl as a “hermaphrodite,” Ashton revealed his elite private-school education, which would have left him familiar with classical literature. He was not referring a person we would now describe as intersex. He was, instead, referencing a Classical-era story told by the character of Aristophanes in Plato’s Symposium.

According to Plato, the earliest humans were round, with two heads, four legs and four arms. They existed in three types: the children of the sun, who looked like two men joined together; the children of the earth, who looked like two women; and the “androgynes,” the children of the moon, who were half-male and half-female. Eventually, fearing the power of these spherical humans, Zeus cut each one in half, dooming them to roam the earth searching for their other half. This explained humans’ capacity for romantic attraction to one another—and also inspired the song “The Origin of Love” from Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

This myth also had the handy side effect of explaining homosexuality and heterosexuality – which might help to explain why the story stuck in the mind of Sir Leigh Ashton, who was himself gay. So when Ashton looked at this bowl, he drew on his own knowledge, expectations and personal experience, and saw one of Plato’s androgynes.

In fact, what this bowl shows is not an androgyne—or a “hermaphrodite”—but a wedding ceremony. In the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, an independent principality established in 1198 by refugees fleeing the Turkish invasion of Armenia, a traditional wedding ritual that involved the couple wearing one upper garment between them. The conjoined couple on the bowl represent this ceremony, and the ears of wheat they hold are a symbol of fertility. This bowl was made in early fourteenth-century Cyprus, where the tradition was probably imported from Cilicia as part of the two states’ intimate trading relationship.

So Ashton’s interpretation of the bowl’s design was wrong. But he was—and still is—far from alone in jumping to conclusions based on what was familiar to him. Every time we look at an object in a museum, we make gendered assumptions about what we are seeing, whether we realize it or not. And these assumptions are always based on our own backgrounds and experience.

Gender-tinted Glasses

This isn’t just about a classically educated curator seeing a Plato myth in a Cypriot bowl. It’s also about the way that gender stereotypes and norms of our own day affect how we look at objects from the past. It can be hard to avoid instinctively looking at museum objects through gender-tinted glasses. For example, if you saw this beautifully carved wooden comb in the V&A, you would be forgiven for assuming it was made for a woman. After all, beauty products today are separated rigidly into binary gender categories; anything that’s advertised as “for men” is usually as plain and unadorned as possible. Fragile masculinity couldn’t possibly handle the vicious assault from a decorated comb.

When it was made in the early sixteenth century, though, this comb was gender-neutral. It was intended as a love token. The French inscription it bears translates as “Of a good heart [I] give this”—but these could be given by women as well as men. Elaborate combs were simply used by everyone. Similarly, because we live in a society that is (far too) heteronormative, it follows that many would assume that the Cypriot bowl shows a wedding between a man and a woman.

Even if we could get away from projecting modern gender-based stereotypes about the use of medieval objects, we also have stereotypes about the medieval period more broadly to contend with. Most popular representations of the medieval world present it as strictly patriarchal—so we might look at this bowl, or this comb, and assume that it was made by a man. Because, we may have been told in ways large and small, medieval women didn’t have access to those professions.

But none of that is necessarily true. And if we manage to get beyond those stereotypes and assumptions, the truth is—rewardingly—a lot more interesting.

What Are We Missing?

What do we lose when we make those gender-based assumptions? First of all, we might miss what many medieval objects—including this bowl and comb—can tell us about medieval women. These objects show how medieval women were far from excluded from the mercantile world. While some trade guilds excluded women from membership, many did not. Even those with rules against female apprentices would allow widows to take over their husbands’ business when he died. The comb-makers’ guild in sixteenth-century France explicitly wrote this into their governance. Research into artisanal workers in medieval Cyprus has also suggested that women were likely to work alongside their husbands—after all, it made sense for both partners to contribute to the family income where they could. If you saw the film A Knight’s Tale, it’s rife with (sometimes wonderful) inaccuracies. But if you assumed the story of Kate, the talented, widowed blacksmith was one of those inaccuracies, you’d be wrong.

Both this bowl and this comb could have been made by female hands. But our assumptions about medieval gender relations mean those women—and all women like them—remain invisible.

Secondly, we might miss the queer and transgender possibilities within medieval objects. This bowl, for example, has a queer heritage that goes beyond Ashton’s interpretation. The most famous example of the garment-sharing ritual shown on the bowl is not an heterosexual wedding, but a bonding ceremony between two men. In 1098, Toros, the Armenian ruler of Edessa, adopted Baldwin of Boulogne as his co-ruler and heir using this ceremony. Toros and Baldwin didn’t have a romantic or sexual relationship (as far as we know) but what this does tell us is that the garment-sharing ceremony was used regardless of the gender of the participants. Toros and Baldwin’s bonding ritual would have, at the very least, carried associations with marriage.

Knowing this history means we should take another look at the genders of the figures on the bowl. And when we do, they aren’t as clear-cut as you might think. While it’s likely that they are a man and woman—only on the balance of probability—their clothing and hair don’t indicate their gender based upon the norms of the time. To both medieval and modern viewers, they are effectively a gender-neutral pair—or perhaps, a pair that the viewer could gender however they liked.

The gendered assumptions we carry around in our heads often lead women and queer people to become invisible in museums of medieval history. This is also affected by how museum curators have chosen to present medieval objects to us. Because we often misunderstand the medieval world as one of total male domination, if a museum label reads “people,” we’re likely to interpret that as meaning “men” unless it’s explicitly stated otherwise. Similarly, unless queer or transgender possibilities are mentioned, we’re likely to assume they didn’t exist. Some museum visitors (or directors, or curators) from marginalised groups might read between the lines and find the history of people like them. But for other visitors, if it’s not on the label, it might just not occur to them.

How To Re-gender, De-gender, or Queer Your Museum Experience

A group of historians working with the V&A and Stockholm’s Vasa Museum are working to change this. Through a project called “Gendering Interpretations,” we’re researching the hidden gendered stories behind medieval and early modern objects at these museums. If you want to see more as the work develops, you can follow me or James Daybell on Twitter: you can also search “gendering interpretations” in the V&A’s Search the Collections database, where our research is starting to be made available. But just as importantly, next time you visit a museum or a historic site, why not think about how to re- or de-gender—and queer—your own museum experience? As a starting point, ask yourself:

- Who made this object? Are you looking at evidence of an unequal economic marketplace, or of hidden female labour?

- What is it made of? Even materials can have hidden gendered aspects. Museums will usually specify materials, but won’t give much detail about how the maker came by them. You might need to use your imagination a bit. For example, is the material something found in the country where the object was made? If not, then acquiring it probably involved contact between different cultures—which might lead us to ask…

- Where did it come from, and where was it going? Many objects are evidence of contact between cultures. Every culture has its own understanding of gender and the roles associated with it. When European colonisers invaded Caribbean islands in the fifteenth century, for example, the strictly patriarchal gender roles and hierarchies of their Catholic culture clashed with the indigenous Taíno society, in which women played important political and economic roles at every level. So objects that are made in one culture, but use material sourced from another—like this tortoiseshell snuff boxhave often played a role in shaking up the gender dynamics of both societies.

- Who is it for? Are there characteristics of an object that make it obvious it was designed for use by a particular gender? If so, what would happen if someone of another gender used it – how could they manage that, and how would they be perceived? Might your assumptions about who it was designed for be wrong—and what does that say about our assumptions of gendered objects now?

- Does it tell other stories? Some objects, particularly luxury items, have designs drawn from mythology. What gender dynamics can you see in those stories?

- What about individual motivations? Sometimes, a museum will tell you that a large group of people “cross-dressed” in particular circumstances (so that they could fight in battle despite being assigned female at birth, for example), or that large numbers of same-sex couples used to share beds. Museums have a tendency to generalise out of necessity. They may say that every soldier assigned female at birth (or AFAB for short) was simply a woman in disguise who, perhaps, wanted an exciting life. Or they may say that men shared beds because of “social convention.” But these people are individuals, not a homogenous group: is it possible that some of them had queerer motivations?

- What kind of gendered glasses does this museum want me to look through? Every museum has to make choices about what kind of stories to tell about the past; usually these come with gendered assumptions. While many museums are now trying hard to highlight the experiences and voices of marginalised people, some still suffer from the kind of stereotyped assumptions about medieval gender that I mentioned above. Even in museums that try hard to challenge stereotypes, assumptions often remain. The displays might assume that every culture shares a Western binary view of gender. They might focus on communicating the gender norms of the past without highlighting how people could break those norms. Always ask yourself: what is this museum telling me about gender? What is it leaving out? What has it left unquestioned? What is unsaid?

- Who can I talk to? Many museums will have staff or volunteers on hand who are bursting to tell you more about the history on display—and just because gender isn’t mentioned in the displays doesn’t mean they won’t know about it. Why not ask them some of these questions and see what you discover?

So when you look at the picture on this bowl now, what do you see?

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.