This is Part 6 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Jennifer Speed. You can find the rest of the series here.

Perceptions of people’s bodies and genders were different during the Middle Ages than they are now. But, it appears that one thing has not changed: a woman’s appearance is still fair game for interpreting her character and her motives.

A contemporary case in point: on January 21, 2017, the Women’s March was held in Washington, D.C. and in cities across the U.S.—the day after the inauguration. An article in the Chicago Tribune noted that:

several conservative commentators took to social media for commentary. Did they critique the marchers’ message? Nope…What they did was make fat jokes.

Male judges and lawmakers quickly joined in the fray in various forums, including on their official social media accounts. The Chicago Tribune article goes on to detail only a small assortment of the ways in which a woman in a prominent public role is judged “on what she weighs, what she’s wearing, and what her hairstyle says about her.”

Judging women based on their appearance is, of course, nothing new. The thirteenth-century English historian Matthew Paris (Mattheus Parisiensis) was just such a man. He felt compelled to comment on the appearance of “nearly all of the women he includes in his works,” the majority of whom he had never seen. This includes a noblewoman, Garsenda, Countess of Béarn. By all accounts, Garsenda was impressive. She successfully negotiated a male-dominated world in protecting her inheritance, her rights, her children, and her status. But Matthew Paris’s negative remarks about her supposed appearance were recycled for centuries. Why? Because future writers found his observation that Garsenda was fat to be too juicy of a detail to leave unrepeated.

Matthew Paris’s remarks might not have gone viral in the modern sense, but they have enjoyed a special currency for nearly eight centuries. Perhaps unflattering remarks about a woman’s body have a timeless appeal. In the case of Garsenda, who is not otherwise well known, Matthew Paris’s anecdote has become a defining epithet. His comment,then, invites two questions: who was Garsenda and why did Matthew Paris write about her in the way that he did?

Mo Money, Mo Problems

Garsenda was born into nobility around CE 1200 in Provence, France. She was the daughter and granddaughter of two strong-willed women who shared her name. Her mother, Garsenda, Countess of Provence and Forcalquier, was a troubadour in her own right. Her father was Alfonso II, Count of Provence, second son of the King of Aragon (whose territories stretched across much of Northeastern Spain and southwest France), and Count of Barcelona and Provence. Garsenda’s marriage in 1220 to Guillem de Montcada, soon to be Viscount of Béarn, connected her to powerful families on both sides of the Pyrenees. In short, she was a powerful woman from a line of powerful women.

But as we well know, nobility doesn’t insulate people from all tragedy. At age nine, Garsenda lost her father, Alfonso, Count of Provence. Alfonso’s death prompted her mother to execute a legal agreement to protect both of her children’s inheritance from other Provençal nobles—including family members—who had designs on their titles. Within a few years, the Albigensian Wars raged throughout Occitania and Provence, and the family of three was forced to flee from Provence to Catalonia, in what is now Spain, for safety.

Tragedy struck Garsenda again in 1229, when her husband was killed in a campaign to conquer Majorca. Guillem’s death left Garsenda with the personal responsibility of caring for their two young children, Constança and Gastó. At the same time, Garsenda was thrust into a very public role when she was forced to contend with the crushing debts left by her husband and parents-in-law when they died. She also had to defend her title to lands on both sides of the Pyrenees mountains—stretching all the way from Aquitaine and Gascony in the west to Majorca in the east. Ambitious men were as eager for her to make good on her husband’s debts as they were to seize control of her lands. Against those odds, Garsenda rose to the occasion. There she was, a young widow with two toddlers who had to face down dozens and dozens of the kingdom’s most powerful men, who were demanding immediate repayment of her husband’s and debts. The wolves were at the gates.

It’s All About the Benjamins

She knew how to play the game. First, she petitioned the king. With support from King Jaime I of Aragon, Garsenda was able to temporarily suspend all financial claims in order to protect assets and titles belonging to her and her children. Lodged among the surviving parchments from the era of King Jaime, now held in the Archive of the Crown of Aragon in Barcelona, are more than 100 individual charters from around 1230-1258 that give us insight into the scope of Garsenda’s actions.

From Garsenda’s surviving charters we find that she assembled a team of advisers, drawn from among Cistercian monks at Santes Creus (a monastery that still stands in Catalonia). These monks became her financial advisers. They helped her assess her debts and apportion payments to her creditors until those debts were satisfied or forgiven. We find in the archives legal agreements that she executed throughout her life on her own behalf.In others, she worked through agents charged with carrying out her direct orders.This is significant. Her dealings over nearly forty years challenge the perception that medieval women lacked agency in their own legal affairs. If women were not allowed agency, nobody told Garsenda about it.

Her plans were so successful that within four years of her husband’s death, Garsenda’s finances had recovered enough for her to make a major donation to reinvigorate a struggling Barcelona convent, Santa Maria de Jonqueres. She would remain involved with that convent, as well as another local one, for the rest of her life. After dispensing with her debts in Catalonia, Garsenda turned to her other problems, namely, her son’s considerable claims to lordships and territories in France and Spain. In order to protect his interests, especially in and around Béarn, she relocated to its capital at Orthez (Ortés). It was there that she established a base of operations for political negotiations. She negotiated with nearly everyone of note: the kings of France, Navarre, Castile, and England, as well as bishops, leaders of religious communities, and local officials. She also ensured her own physical safety by reinforcing the castle there. Even as her son reached the age of majority and could rule in his own name, Garsenda never stepped away from center stage as “countess and viscountess of Béarn.”

Growing conflict among the kings of Castile, France, and England over claims in southwestern France eventually found their way to Garsenda’s doorstep. But it was a major marriage alliance and a military campaign that brought Garsenda into Matthew Paris’s orbit. In 1236, Henry III of England married Garsenda’s niece, Eleanor of Provence. In doing so, he had hoped to build alliances in Provence against the king of France. Soon after the marriage, scores of Eleanor’s maternal Savoy relatives came to England and were settled with titles and estates. Even though Eleanor’s Savoyard kin came at Henry’s invitation, their arrival prompted resentment against foreigners by the English. This tension was captured in contemporary English historical writings,including those of one Matthew Paris.

Matthew Paris: Playa Hater

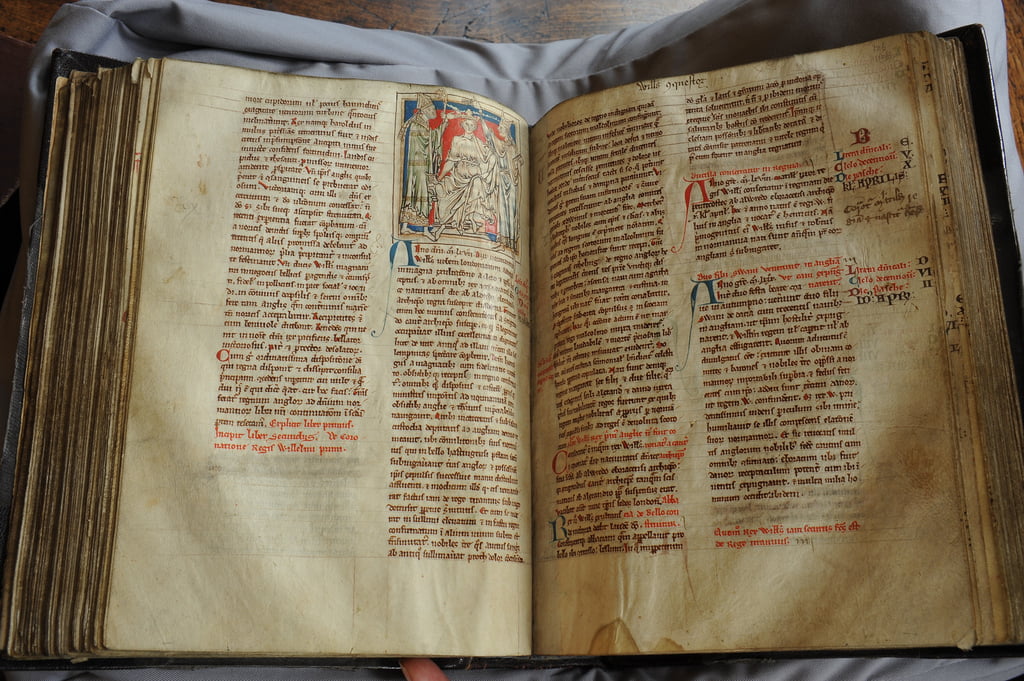

Self-portrait of Matthew Paris. British Library, MS Royal 14.C.VII, folio 6r.

Matthew Paris (ca. 1200-1259) was a monk at the monastery of St. Albans on the outskirts of London. Though he spent most of his adult life at St. Albans, he was well connected in political and royal circles and even assumed diplomatic duties on behalf of the king of England. As historian Rebecca Reader notes, “Cloistered he may have been. Closeted he wasn’t.” He knew very well what was going on in the wider world, thanks to his extensive connections.

Before Matthew Paris’s arrival at St. Albans, its monks were already renowned for their historical writing. He solidified St. Albans’ reputation for producing histories by composing and illustrating a number of texts, some of which drew from older histories. Among Matthew Paris’s chronicles and biographies is the Chronica majora, which offers especially rich history for the 1240s and 1250s.

Henry III at the court of Louis IX. British Library Royal 16, G VI f. 246.

Included in the Chronica are the details of Henry III’s ill-fated military campaign against Louis IX in France in 1242. Apparently, the French forces soundly defeated Henry. Afterwards, he retreated to Burgundy to regroup. There, Matthew Paris tells us, Henry was visited by Garsenda, who had come to see her niece Eleanor and her newborn grandniece Beatrice. He writes,

In that time, a certain woman, singularly strange (monstruousa) because of her prodigious size, the countess of Béarn, came to the king with her son Gastó and sixty knights zealously desiring money.

According to Matthew Paris, the contingent accepted money from the king, stayed for an unreasonable amount of time, and left Henry impoverished. A few passages later, Matthew Paris notes that the countess and her son had wrested the money from the king. Matthew Paris’s word choice “extorquentibus” suggests force or violence. In only a few words, Matthew Paris reduced Garsenda to a fat, awful, greedy woman who took advantage of an English king.

Hit ‘Em Up

Matthew Paris’s assessment of Garsenda was not only unflattering, it invited embellishment, even by Matthew Paris himself. In a work known as the Flores historiarum, long attributed to a “Matthew of Westminster” (but in fact written by Matthew Paris), he refers to Garsenda as “the giant woman.” He also adds that her “corpse, now the inheritance of many maggots, could burden an empty litter.” For emphasis, either Matthew Paris or a later editor added to the margin the phrase “an absurd women’s deception” to draw attention to Garsenda’s supposed trickery of King Henry III.

Damn.

A French historian, Jacques-Joseph Faget de Baure, in his Essais historiques sur le Béarn (Paris, 1818), provides a mild paraphrase of Matthew Paris’s assessment. But an Englishman writing just over a decade later felt compelled to read more meaning into Matthew Paris’s own words. In his work on English manners in the later Middle Ages, the English author and editor Thomas Hudson Turner heaps criticism on Henry III for his profligate spending, with one example being the way in which he “idled his time” and “expended large sums of money in feasting the Viscountess of Bearn” and others. He refers the reader to the 1684 edition of Matthew Paris’s Chronica majora, and provides the phrase “mulier singulariter monstruosa, et prae grossitudine prodigiosa” (roughly translated as: a singularly monstrous woman of exceptional girth). But the Chronica majora never said anything about feasting. In a slight of hand, then, Turner linked Henry’s wasteful spending on feasting with Garsenda’s supposedly large size. A reader could be forgiven for thinking that Matthew Paris had called Garsenda a glutton—though he never said anything of the sort.

Nineteenth-century Anglo-Irish travel writer Louisa Stuart Costello was more spare in her assessment of Garsenda in a two-volume travel book on Béarn and the Pyrenees: A Legendary Tour of the County of Henry Quatre (Béarn, 1844). Therein she describes the castle in Orthez that was owned by “a warlike lady, called the La Grosse Comtesse [The Fat Countess] Garsende de Béarne.”

A contemporary historian has made that link even more explicit, but it appears to be entirely invented. In a scholarly article from 2004 on Alfonso X, a piece in which Garsenda plays no role whatsoever, her appearance is still described in connection with her son’s exploits. The author invokes the name of:

Gastó, Viscount of Béarn, a man of enormous vitality, inherited without doubt from his mother, the immense countess Garsenda, whose gargantuan appetite caused fear in the Angevin court and whose genes seem to have been transmitted to her granddaughter.

Without any evidence, a contemporary author imagines gluttony and obesity as being part of the family’s female DNA, extending from grandmother to granddaughter. A citation offered is for multiple references, but none actually contain a description of Garsenda’s appetite, fear in the Angevin court, or transmission of her genes to subsequent generations.

Perhaps this shows the power of an insult about a woman’s body. More than seven centuries after Matthew Paris took a jab at Garsenda—someone he had certainly never met or even seen—only the medieval man’s derision is worth invoking. Matthew Paris targeted Garsenda because of her political activity. But he made it memorable by attacking her body. The context has completely faded away. All that remains is the insult.

Legacy

Male judgment of the female body is undergirded by something even more insidious than rudeness or crudeness: a “long history of powerful men using body-shaming as a way to maintain the status quo.” As the historian Pierre de Marca notes in his Histoire de Béarn (Paris, 1640), Garsenda made a lot of enemies, “like Matthew Paris, the English historian.” As writers have carried forward and embellished Matthew Paris’s description of Garsenda, what has been forgotten is the cultural climate in which Matthew Paris lived and wrote. His histories reflected widespread resentment of Eleanor’s foreign relatives who decamped to England. Garsenda represented yet another one of Eleanor’s kinfolk who was ostensibly bleeding the king, “leaving him defeated and impoverished.”

Matthew Paris’s telling of the story leaves out this: Garsenda had gone to Henry after his humiliating military defeat,offering the services of sixty of her own knights to a king desperately in need of local allies. The leader of the armies typically paid knights’ expenses. Garsenda was entirely within custom to ask for a per diem for her knights, and it makes sense that Henry would have been generous to his guests. Garsenda knew how to manage her finances. It was not her fault that Henry didn’t know how to manage his.

It is worth noting, though, that even

though Matthew Paris is derisive of Garsenda’s appearance, his description of

the scene at Henry’s court is accurate. It depicts Garsenda, and not her son,

as taking the lead. Perhaps inadvertently, he captured an element of truth.

Garsenda was an immensely capable, politically savvy woman who navigated a male

world and negotiated her own terms. Even Matthew Paris failed to hide that.

Further Reading:

Rebecca Reader, “Matthew Paris on Women,” Thirteenth Century England VII: Proceedings on the Durham Conference VII (1999): 153-160.

John Shideler, A Medieval Catalan Noble Family: The Montcadas, 1000-1230 (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983).

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.