This is Part IX of The Public Medievalist’s continuing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Dr. Clare Vernon.

Go back to the beginning of the series here.

This is the medieval church of St Nicholas, in the city of Bari in Southern Italy, which was built in the eleventh century to house the bones of St Nicholas (aka Father Christmas, aka Santa Claus). From the outside, it looks exactly how you would expect a medieval church to look, right? It looks old and Christian, and perhaps quintessentially European. But inside, we find intriguing evidence showing how medieval culture was not exclusively Christian or European.

Discovering Islamic Culture in Christian Space

Here is the most sacred part of the church: the area behind the main altar, where we find Bishop’s throne. The seat, as you can see, is held up by three men of different ethnicities.

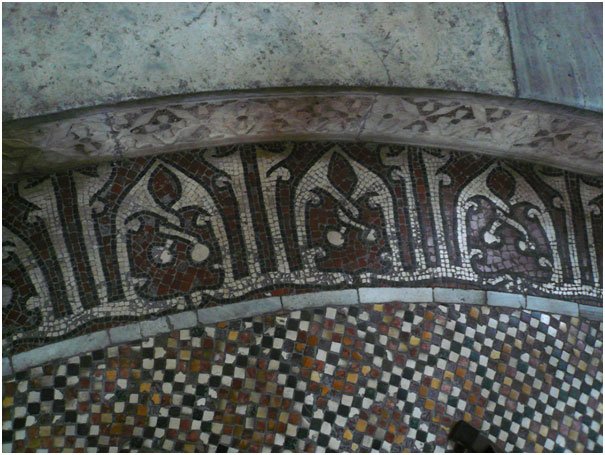

The two men at the corners are modelled on ancient Roman images of slaves; they are wearing loincloths and grimacing under the weight of their marble, and Episcopal, burden. They depict people of two different ethnicities: one has hair that coils into tight ringlets, and the other has hair that is coarse and wavy. Between them, a third figure somewhat nonchalantly helps to support the Bishop’s seat. Thanks to historian Rowan Dorin’s excellent research on how this figure is dressed, we know that he is a Muslim (the hat in particular is a dead giveaway). Not only that, but the style of this sculpture is very similar to contemporary Islamic sculpture from Egypt. If we zoom out and look at the surroundings of the throne, we can see further evidence of Muslim culture. The magnificent floor on which the throne stands is made up of small pieces of multi-coloured stone tessellated to form shapes and patterns.

Running along the wall behind the throne is a band of mosaic decoration made up of repeated Arabic letters. Perhaps this is not what you expected to see in a medieval church.

So how did Islamic culture find its way into this Christian space? And how would it have been perceived by the medieval people who built the church and worshipped within it?

Southern Italy and Diversity in the Mediterranean

Today, the Mediterranean Sea is encircled by nations predominantly made up of Muslims, Jews, and Christians. The current refugee crisis is a poignant illustration of how navigable—if treacherous—the sea is, and how connected the people who live on its shores can be. In that respect, things were no different a thousand years ago (or indeed two thousand or five thousand years ago). For a better understanding of this, let’s look in a bit more detail at the south of Italy at the time the church of St Nicholas was built.

In the early Middle Ages (roughly from the sixth to the eleventh century), the city of Bari and the surrounding area was ruled, at different times, by Muslims, Orthodox/Greek Christians and Catholic/Latin Christians. For about twenty years in the ninth century the city was under Muslim rule: a congregational mosque was built, and the Christian population lived under Islamic law. Later, the city was conquered by the Holy Roman Emperor Louis II and reverted to Christian rule. For the rest of the Middle Ages, the region oscillated between being governed by representatives of the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople (who were Greek-speaking, Orthodox Christians) and local Italian princes (Catholic Lombards originally from what is now northern Italy, who used Latin as their written and sacred language). In the eleventh century, when the church of St Nicholas was built, the whole of southern Italy was conquered by Normans, who had arrived from northern France.

Throughout this period, the city of Bari had grown rich and famous through commerce. Businessmen from Bari travelled the length and breadth of the Mediterranean. Mainly they travelled to ports in the south and east of the Mediterranean, where they traded with Muslim and Byzantine merchants. They sold Italian staple products, such as timber, olive oil and wine, and purchased sought-after luxuries such as silk, spices, gold and ivory. Returning home, they sold these for significant profits, and then repeated the process. As a consequence of all this repeated conquest and continuing trade, the city had a diverse population. The majority of the citizens were Latin Catholics and Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians, as well as significant communities of Armenians and Jews. There may have also been a small, stable, community of Muslims in the city but there isn’t enough evidence for us to be sure.

Certainly, the merchants of Bari would have been on familiar terms with their Muslim business partners and with Islamic art. Exchange and dialogue with the Muslim world was crucial to the economic prosperity of the city. The Arabic mosaic pavement in the church of St Nicholas was probably made by Christian artists copying from an object made in another part of the Mediterranean by Muslim artists—probably a textile or a piece of metalwork or ivory.

What is ‘European Culture’?

This is a tiny snapshot of the many thousands of interactions that took place between Muslim and Christian people in the Middle Ages. In the first few months of 2017, bringing Islamic culture into Christian sacred space has been both topical and controversial. In January, a Qur’an recitation in Glasgow cathedral sparked hostility. In February, an exhibition in Gloucester cathedral, which explores different faiths was vandalised. Last week, Channel 4 News broadcasted a piece on the neo-fascist self-styled “alt-right” in the UK. One of the participants stated that her objections to immigration stemmed from her belief that, “European culture [is] being snowed under”.

The sacred space in Bari, and other medieval churches, reminds us that when we hear statements such as these we need to question them, and push back against their assumptions and implications. There is an underlying assumption in that statement that “European culture” is a homogenous, static and monolithic entity, and another that European culture can be diluted (or perhaps polluted?) by sustained contact with people who are thought to be part of a different culture. In reality, when we study the history of European culture, it reveals to us that Europe and its many cultures have been woven over centuries from thousands of diverse threads. It has never been a homogenous entity with clearly defined boundaries, and it never will be.

Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more about diversity in medieval Mediterranean art, these are some good places to start.

- ‘Diversity by design’, Apollo: The International Art Magazine, June 2016, Volume CLXXXIII, No. 643, pp. 80–85.

- Museum With No Frontiers.

- Qantara.

The Public Medievalist does not pay to promote these articles, so we would love it if you shared this with your history-loving friends! Click to share with your friends on Facebook, or on Twitter.

Same goes for Portugal and Spain! I did a photo exhibition back in 2010 precisely on this topic in the Algarve region of Portugal.