This is Part XLIII of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Matthew Vernon. You can find the rest of the series here.

This is Part XLIII of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Matthew Vernon. You can find the rest of the series here.

To read more about ways in which African Americans strove to forge a more comprehensive, difficult, and ultimately positive conception of the medieval world, read Dr. Vernon’s new book The Black Middle Ages: Race and the Construction of the Middle Ages. It is available through Palgrave McMillan, or on Amazon.com now.

Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther was a cultural landmark. Countless articles have been written about its impact. But none have explored how medieval it is. Black Panther’s plot could well be taken from the genre of “medieval romance”—tales of medieval heroic adventure.

The story of Black Panther revolves around princes and princesses, a hidden kingdom, the ethics of combat, and the responsibility of rule. And part of what made this movie surprising was how it illustrates how race functions in this type of story. Race is a critical difference through which those familiar story elements gained new meaning. The “commoner who learns that he is indeed a prince” is a very old story type. But as part of Black Panther’s central narrative, this is transformed into a story of the African Diaspora and the problems of retaining any sense of cultural identity.

Looking at Black Panther through a racial lens enables us to see African heroes in an otherwise overwhelmingly white genre. This looks very modern, but it is not new. In fact, African-American writers’ creative connection to medievalism is nearly as old as the United States itself.

African-Americans have long pushed back against the notion that whiteness, and “white medieval history,” are the full story of America’s foundation. African-Americans resisted and subverted the dominant myths of the nation. Looking at these acts of resistance can tell us a great deal about alternative—but equally valid—ways of perceiving American history.

White Medievalism in America

Medieval narratives have been used politically by white Americans since the foundation of the country. For example, Thomas Jefferson argued that “Anglo-Saxon law” was the basis for America’s government. He reasoned that this made the country distinct from England whose government, he claimed, was based on Norman law:

Are we not the better for what we have hitherto abolished of the feudal system? Has not every restitution of the antient [sic] Saxon laws had happy effects? Is it not better now that we return at once into that happy system of our ancestors, the wisest & most perfect ever yet devised by the wit of man, as it stood before the 8th century.

Jefferson wrote this in a 1776 letter; in that letter, he simultaneously argued for the rights of American colonists to break free from Great Britain and also for a continued military campaign against Native Americans. Jefferson entangles freedom and forceful subjugation.

And more, he does this by appealing to “Anglo-Saxonism.” Anglo-Saxonism is an ideology that used Anglo-Saxon language, culture, and genealogical heritage (real or imagined) as the spine around which the nation was imagined. In other words, he imagined himself, and his nation, the heroic ancestors of (what he imagined were) heroic 8th century Germanic tribes.

But this is no idle fantasy. Reginald Horsman, author of the groundbreaking book, Race and Manifest Destiny (1970), described the terrifying ends to the logics of Anglo-Saxonism:

the reign of world peace, order, and morality was to be established by the Anglo-Saxon-Teutonic Christians, and if necessary it was to be founded on the bodies of inferior races.

Anglo-Saxonism is one branch of a broader system of racist misappropriations of medieval iconography and language. These appropriations have haunted the United States since its inception, and been part of the rhetoric around national expansion, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and infused into all-too-familiar white supremacist groups like the Klu Klux Klan.

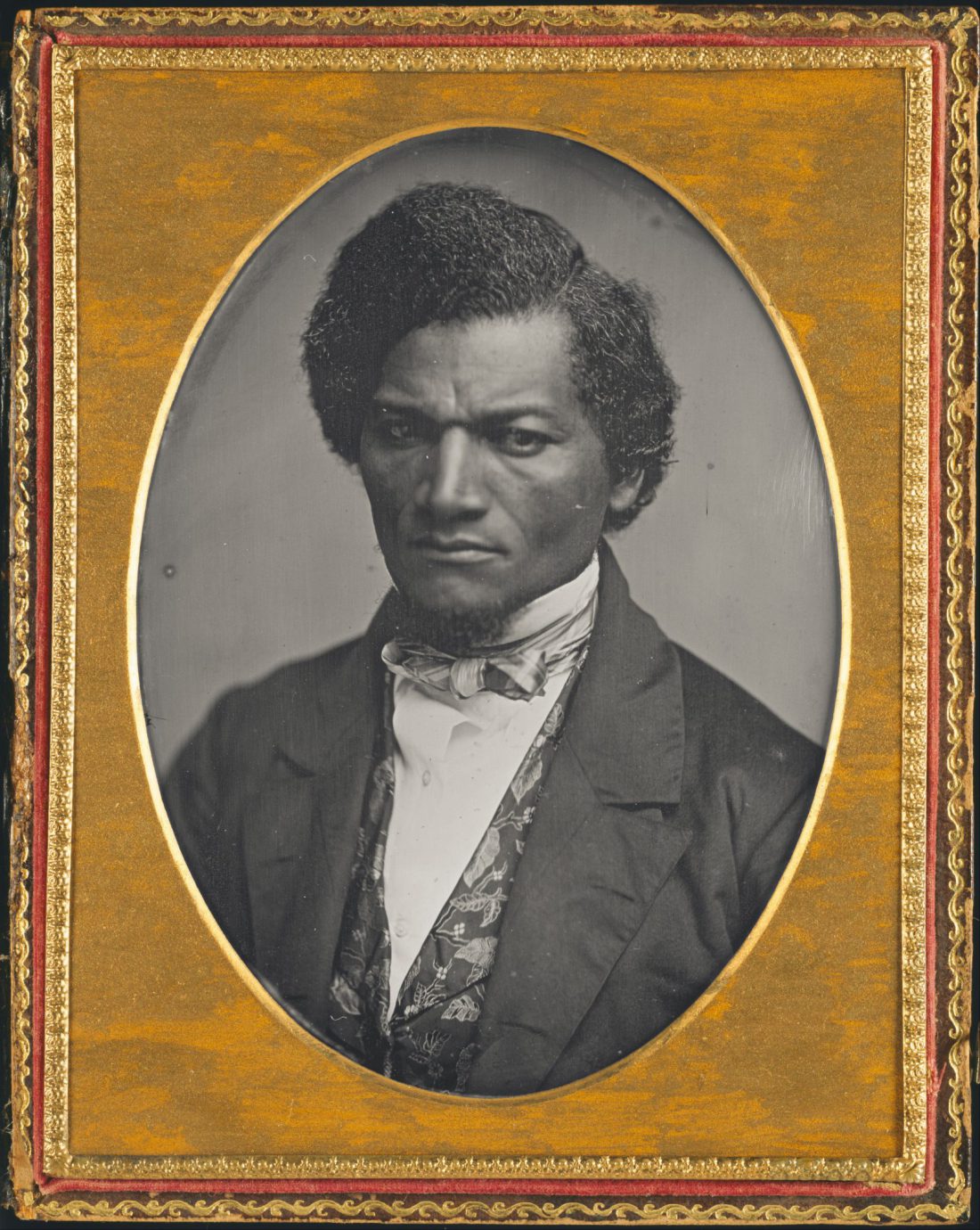

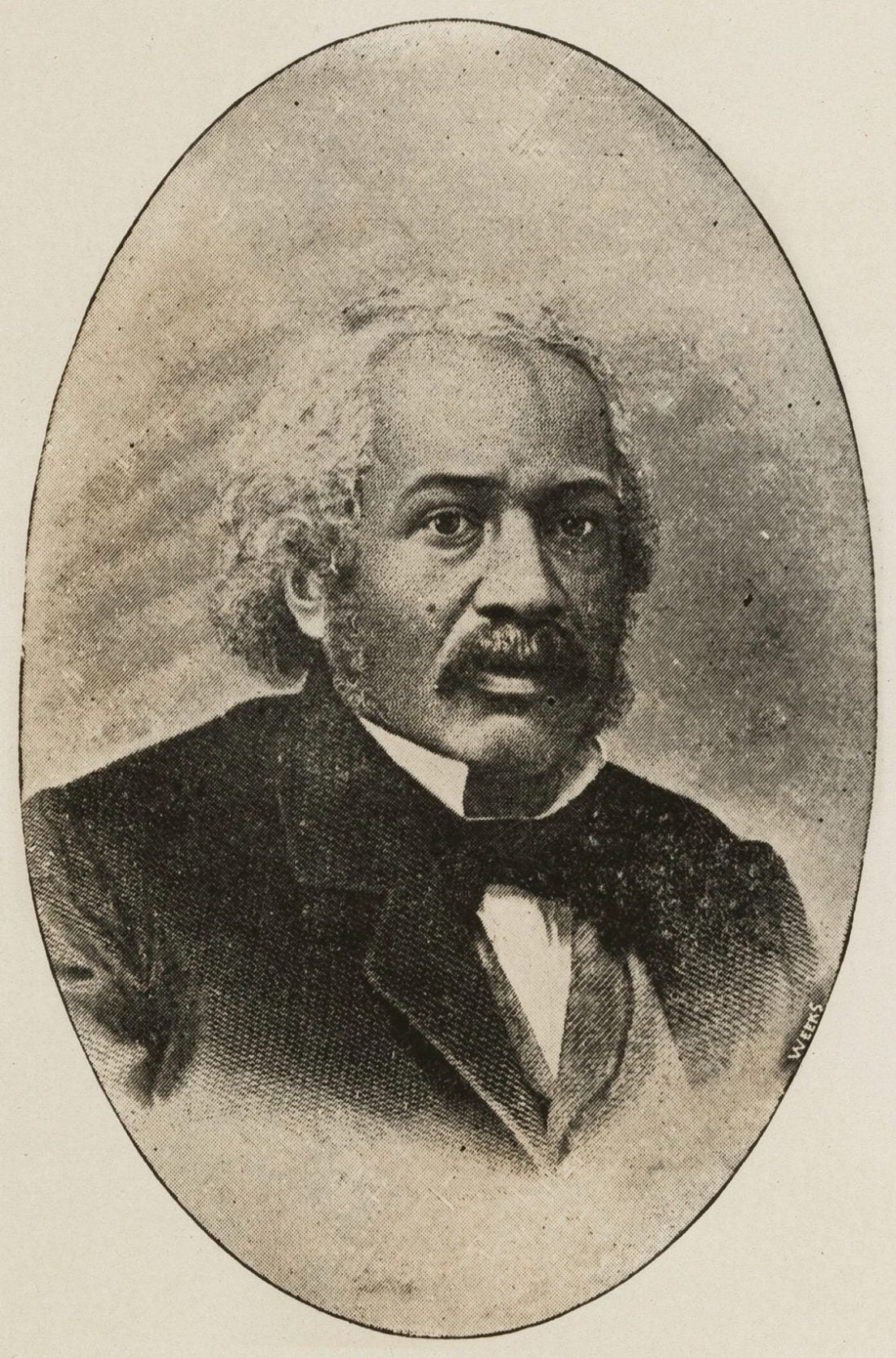

Frederick Douglass’ Medieval Freedom

African-American writers and intellectuals fought these currents of white supremacist ideology. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they used the Middle Ages to reorient the ways in which they felt they belonged, and were seen by others to belong both within the United States and around the world.

The most famous example of this is Frederick Douglass. Though he is known as Frederick Douglass today, he did not always carry that name. He was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. But upon escaping to the North, he changed his last name from Bailey to Douglass. He did this at the suggestion of his benefactor in New Bedford, Nathan Johnson. Johnson came across the name “Douglas” while reading Sir Walter Scott’s romance, The Lady of the Lake.

Not only did Douglass adopt the name, but when traveling to Britain to make his case for abolition, in an 1846 letter he compared himself with pride to a medieval Scottish chieftain, James Douglas, nicknamed “black Douglas”:

Frederick Douglass, the freeman, is a very different person from Frederick Bailey (my former name), the slave. I feel myself almost a new man—freedom has given me new life. I fancy you would scarcely know me. I think I have altered very much in my general appearance, and know I have in my manners. You remember when I used to meet you on the road to St. Michaels, or near Mr. Covey’s lane gate, I hardly dared to lift my head, and look up at you. If I should meet you now, amid the free hills of old Scotland, where the ancient “black Douglass” once met his foes, I presume I might summon sufficient fortitude to look you full in the face; and were you to attempt to make a slave of me, it is possible you might find me almost as disagreeable a subject as was the Douglass to whom I have just referred. Of one thing, I am certain – you would see a great change in me!

Douglass positions himself transnationally. He has freedom within the United States. But more broadly, he feels an unexpected transformation through his journey across the Atlantic.

Douglass rejects Jefferson’s “Anglo-Saxonist” logic, which saw white Americans empowered through their links to a medieval past. Instead, he suggests that an African-American could better understand freedom by escaping a fundamental American political structure—slavery—and by seeking his own connections to medieval history in Britain.

Medievalism in Novels by African-Americans

Charles Chesnutt, in his novel The House Behind the Cedars (1900), goes a step further than Douglass in thinking about the relationship between the Middle Ages and African-Americans. The novel is broadly about a mixed-race woman attempting to pass as white in the South soon after the Civil War. In it, there is a mock-jousting scene in which “knights” arm themselves in cardboard and gilt paper. This ostensibly pokes fun at Southern notions of chivalry borrowed from Walter Scott’s wildly popular Ivanhoe. But Chesnutt does something quite surprising with the novel as a whole: he fashions his main character after Ivanhoe’s heroine. His heroine and Ivanhoe’s even share the same name: Rowena.

At the end of the novel, she dies while fleeing from a white man of “the proud Anglo-Saxon race” and an African-American man who both seek to marry her. Positioning Rowena as akin to the heroine of Ivanhoe heightens the tragedy of the novel’s conclusions; this virtuous woman is destroyed by the paradoxes of American racial ideologies. She is considered guilty of the “crime” of trying to pass as white and, when exposed, moves to the margins of society and suffers from the impermissible erotic desire of her white suitor. Everyone suffers as a result.

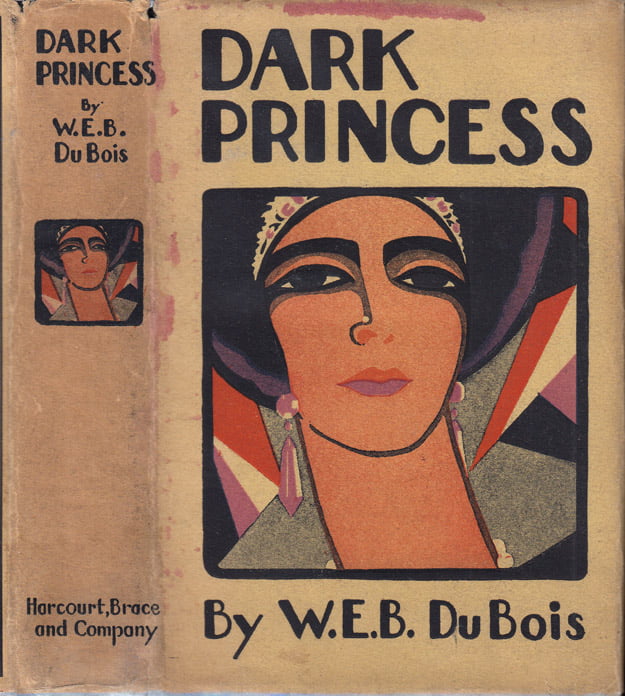

Other African-Americans also used medieval narratives and tropes not only to make political points, but also to express a genuine love of the Middle Ages. W. E. B. Du Bois, in addition to his celebrated sociological work, also wrote a series of speculative fiction stories that borrow heavily from medieval ones. His novel Dark Princess (1928), which he calls a romance, fully inhabits the form of the medieval romance. This is not only reflected in the titular princess, but also in novel’s loose structure of vignettes that test the main character, Matthew. At one point in the novel, the princess even likens him to one of King Arthur’s knights, claiming that Matthew failed in a test to prove his live to her:

Like Galahad you would not ask the meaning of the sign. You would not name my name. how could I know, dearest, what I meant to you?

Throughout his career Du Bois used romance tropes in his writing, such as knights and questing. For Du Bois, the goal of using these tropes was to position the project of emancipation within a context that was much larger than that of the nation.

For example, there is a love story at the center of Dark Princess. In the novel, the protagonist Matthew is denied a career as an obstetrician because of his race. Devastated, he travels to Germany where he meets, and falls in love with, Princess Kautilya of Bwodpur, India. Their love story symbolizes his desire to imagine unity between all people of color across the globe. However, Du Bois also seemed to simply enjoy creating genre fiction that featured characters with whom he could identify. Many fans of Black Panther surely understand the appeal of such a simple change.

Recovering This History

African-American intellectuals also frequently critiqued the notion of “pure blood” deriving from the medieval period. They did this by pointing to the number of ethnic identities coexisting in medieval Britain. In 1859, the abolitionist and physician James McCune Smith argued that the meeting and cooperation of medieval peoples was a strength that contributed to Britain’s success:

[T]he frequent admixtures or amalgamation of variously endowed men which grew out of these repeated invasions, resulted in a composite intellect, greater in force, wider in grasp, more active in detail, than could have grown out of any one tribe or race, Cimbri or Celt, Angle or Norman, which ever dwelt on the British isle.

Smith’s account of British history has clear and pointed implications for a nation seeking to exclude a significant portion of its population on the basis of race and ethnicity. The nation’s continued rise would depend upon inclusion and learning from difference.

Many examples of African-Americans working on medieval topics are remembered out of context, if they are remembered at all. In 1884, Cordelia Ray wrote the poem “Dante”, which lingers over Dante’s exile and political alienation. It is easy to connect this focus on exile and alienation with the frustrations African-Americans had with a political system that had begun to abandon its promises of equal rights to all of its citizens.

For another example, look at the image at the top of this article. It is a painting by Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872). Duncanson was once internationally-renowned landscape painter, but is now largely forgotten. Like Douglass, Duncanson gained the inspiration for this painting during a trip to Scotland—he chose to depict a site featured in Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake. This painting teeters between being merely an exercise in form (albeit an impressive one) and signifying an African-American interpretation of a text that has powerful connections to Scottish nationalism and independence movements. This painting reminds us how much of the context around this African-American work—and others like it—has been lost or ignored.

Other African-American artists, writers, and poets—such as the first generations trained in the humanities after the Civil War—touched upon medieval subjects for a variety of reasons. They used the Middle Ages in their work to demonstrate their erudition. They used it to situate contemporary racial problems within a long historical trajectory. They used the medieval to borrow from the readily accepted meanings that accompany medieval genres. They used it for all the reasons that artists, writers, and poets use the Middle Ages.

Decolonizing the American Mind

To return to where this article began, you can argue that Black Panther “decolonizes” its narrative by broadening the roster of voices working on and featured in superhero films. More importantly, the perspective the movie takes on the character of Black Panther has shifted from his early comic-book days as an exotic character to be wondered at, towards his current status as a popular character that challenges modes of storytelling familiar to Western audiences. This is particularly true in how it challenges the medieval romance.

In this way, Black Panther is part of a long tradition. Similarly, one might say that this reparative work—of creating an ever-expanding and inclusive Middle Ages—has been part of medieval studies since nearly the country’s founding. But this was not done by white people. It was done by African-American writers, poets, artists and intellectuals.

With their groundbreaking work, these creative people tried to move the public imagination of the Middle Ages. They fought to shift it away from a model that assumes that European whiteness was the primary medieval identity categories. And more, they strove to forge a more comprehensive, difficult, and ultimately positive conception of the medieval world.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.