Spoiler Warning: This article contains spoilers for the series finale of Game of Thrones.

“History is written by the victors.”

It’s a pithy, if often incorrect, phrase. History is often not written by the winners. It’s written by the writers. And those writers, no matter what side of which conflict they found themselves on, always brought themselves, their biases and their prejudices to the histories they wrote. Many a conquering hero has been rendered a villainous tyrant by an historian. Many rebellious rabbles have been reframed as a glorious revolution with the stroke of a pen. Every nation that exists was built by stories well before they were built by laws.

In Game of Thrones you could rightly say that, as the show came to a close, racism, sexism, and ableism are certainly candidates for the title of the ultimate winner of the Game. But in the final denouement of the series, the show meditates on history and history-making in a way that shakes up the traditional narrative that history is written only by the winners. It shows us three characters making, and remaking, history in their own image and for their own purpose. The histories that they make tell us as much about our contemporary ideas of how history is (and should be) made as they do about the world of Westeros.

So, who wrote the history in Game of Thrones? Who won?

Archmaester Ebrose

First, the obvious answer. In the small council meeting we are shown in the flash-forward, Tyrion, hand of the new king, is given a book by Samwell Tarly, who proudly proclaims it to be: “A Song of Ice and Fire. Archmaester Ebrose’s history of the wars following the death of King Robert” (in an obvious wink-and-a-nod to the A Song of Ice and Fire books upon which the show is based). Tyrion then scours the pages, inquiring whether the Archmaester has treated his legacy kindly or not. Sam can only say, diplomatically, “I don’t believe you’re mentioned.”

It’s meant to be a laugh line. But a sad one. It’s funny because Tyrion’s ego can’t really accept his obscurity. But that obscurity, and our ego in the face of it, is something almost everyone can share with Tyrion. In that moment, the audience is forced to accept that, while people famously see themselves as the protagonist of their own story, few (if any) of us will even be footnotes in future histories. This is a brutal fact of life, no matter what mountains we may climb, or trials we may face in our lifetimes.

But we in the audience know this to be a kind of injustice. Tyrion, despite his seeming inability to make a good decision after season 5, was a major player in the events of the show. To see him written out of the official history requires some explanation. Was it because his actions were often in the private, rather than public sphere? Was it because he was an administrator and dealmaker rather than a king of a commander? Was it because he is a dwarf?

Writing history is a violent act. For all of the threads that even the most judicious of historians uses to weave their tapestry, other threads are cut or left behind. And all of it is at the mercy of the prejudices and priorities of the historian, who ultimately decides not just the “simple” matter of who is right and who is wrong, but who is worthy of being remembered and who is not.

This is especially—though by no means exclusively—true of medieval chronicles. Part of the work we have been doing here at The Public Medievalist is recovering and presenting the voices of people who were disregarded by the major medieval sources, or worse, were disregarded by later historians. Those later historians were the very ones who decided which sources were “major” and which ones were not—which stories were worth retelling and which were not. But there are also those whose stories will never be recovered—disproportionately the stories of those who are poor, are disenfranchised, are women, are black, brown, indigenous, or people of color, are LGBTQ+, or are people with disabilities.

People like Tyrion. People like you. People like me. What was done to them was a violence that cannot be undone. So while we may laugh at this pot shot against Tyrion Lannister’s ego, we should remember that we are also laughing at ourselves, or, at the worst, at those who have been relegated to the margins of history.

Brienne of Tarth

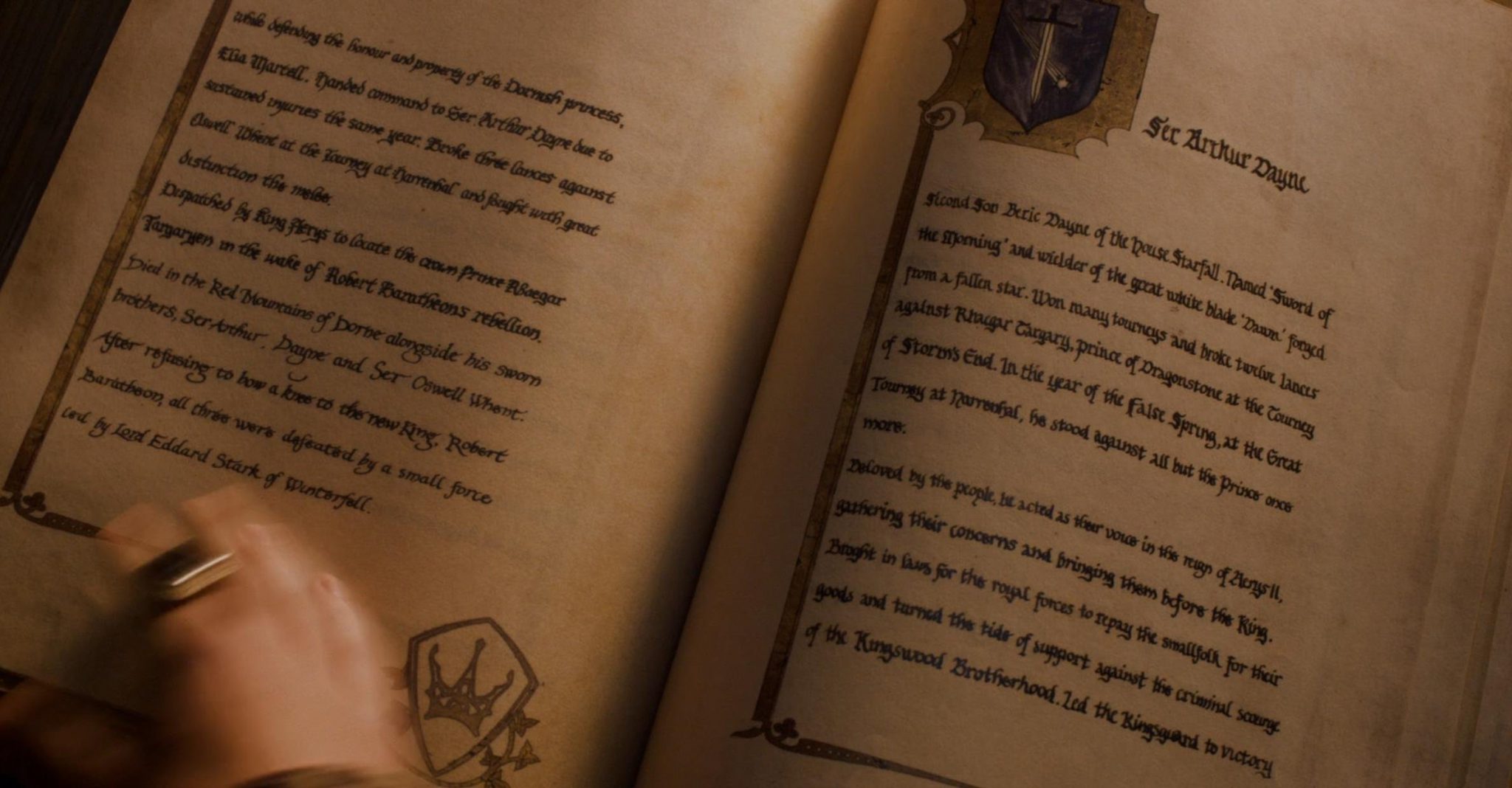

The second history writer we see is Brienne of Tarth. We find her as a newly minted Lord Commander of the Kingsguard; she is adding to Jamie Lannister’s entry in The Book of Brothers that chronicles the heroic exploits of every member of the Kingsguard throughout its history. Medievalists on twitter snarkily lost their minds over her poor scribal technique (she closed the book before letting the ink dry—a rookie mistake that will smear Jamie’s life story all over the facing page!!!). But in her work is something more important than a scribal mistake.

One of the questions shot throughout the show is whether or not Jamie is a hero. He, especially in the first few seasons, cuts the image of the chivalric hero: chiseled jaw, gold armor, prowess, and swagger for days. But the show also begins as a grimdark satire on chivalric fantasy: the knight seemingly best suited for King Arthur’s court is shown to be cruel, deceitful, and, icing on the cake, in an incestuous relationship with his twin sister (which is perhaps the only answer to a weird joke about what if Oedipus and Narcissus had kids).

But as the show goes on, Jamie lurches from villain, to anti-hero, to sort-of hero, to tragic figure. He is shown to not always be an amoral monster, and is revealed to have made great personal sacrifices for the good of everyone when he assassinated the Mad King. He defects from his sister’s army to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with people who hate him against the army of the dead because he knows it is the right thing to do. But once that is done, he loves-and-leaves Brienne and defects back into the arms of his evil sister, where he dies.

So, all in all, Jamie’s complicated. He’s an especially complicated depiction of knighthood. He is neither the stereotype of gleaming chivalry nor just the counter-stereotype of the brigand-in-fancy-armor that contemporary audiences have come to expect.

But when Brienne sits down to finish Jamie’s story, all of this falls away. We know Brienne’s feelings about Jamie are complicated; she looked up to him. She loved him. And, just after consummating their love, he callously left her behind to go die with his sister. If anyone is going to be objective about Jamie Lannister, Brienne of Tarth is not that person.

But she is.

Ish.

But Brienne seems to understand that The Book of Brothers is not about the reality of the person, but about the legacy and honor of the institution of the Kingsguard. The Kingsguard is reflected by the text. The book is history-as-mythmaking, and the scene shows the viewer, in real time, the sausage-making of history. Even—especially—historical authors who were anonymous, and wrote with as much dispassion as Brienne did, are ultimately not necessarily telling the objective truth. It is easy to get suckered into believing that a text presented seemingly without emotion is closer to the truth than one that wears its biases on its sleeve. But that simply isn’t so.

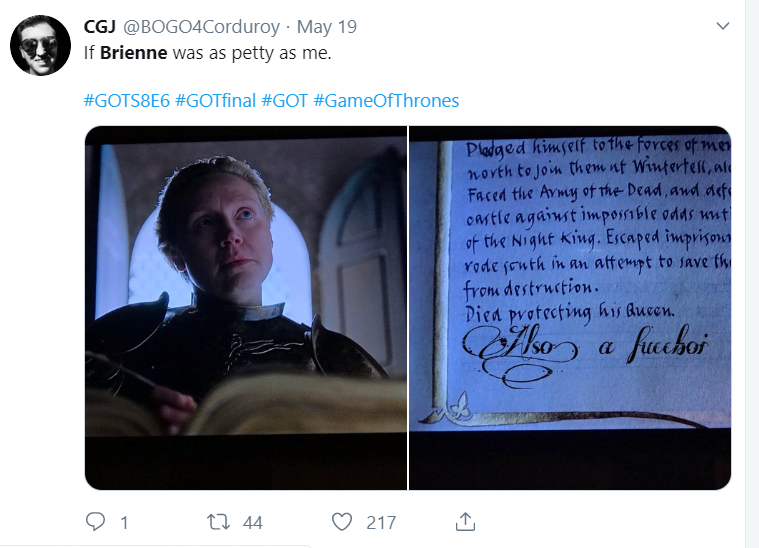

In the immediate aftermath of the episode, that moment was thoroughly meme-ified on social media. My favorite version was the meme that simply added to the end: “Also a fuccboi.” Because that is much closer to Brienne’s truth than what was ultimately committed to the annals of Westerosi history.

So, as in Game of Thrones as in actual history, objectivity is an illusion, as often as not hiding the truth by erasing the author’s subjectivity as revealing it. Which brings us very neatly to:

Brandon Stark

Interestingly, the reason for Bran’s election as the new King of the realm is, in part, based upon his history. When Tyrion proposes choosing Bran, he begins:

I’ve had nothing to do but think these past few weeks, about our bloody history, the mistakes we’ve made. What unites people? Armies? Gold? Flags? Stories. There’s nothing more powerful in the world than a good story. Nothing can stop it. No enemy can defeat it. And who has a better story… than Bran the Broken?

Immediately, Game of Thrones fans on Twitter cried foul, and not just because the moniker “the Broken” is eye-rollingly ableist. Several others in that council had stories that were as good or better. Bran’s story, especially as Tyrion characterized it as “he knew he’d never walk again, so he learned to fly…” can be read as the apotheosis of inspiration porn. Bran had shown no interest in or aptitude at leadership and, since becoming the supernatural Three-Eyed Raven, had shown a callous disregard and total disinterest in the people around him. Not exactly leadership material, especially when compared to his sister Sansa, who had survived incredible abuse and became a competent and capable Queen in the North.

But what seems to clinch it for Team Bran is Bran’s position as a super-historian—or at least, as the public stereotype of the perfect historian. Having taken the power of the Three-Eyed Raven, Bran can enact the fantasy of many historians: he can walk, unseen, any time and place in the past and observe events as they occurred. He has shown that this ability allows him to cut through lies and deceptions, and upend long-held myths. He has even shown a limited ability to rewrite the past, and thus his present. And because he knows the past, he knows what needs to happen in order for the future to turn out well.

But taking on the knowledge of the entirety of human history renders Bran dispassionate, emotionless. He embodies is the fantasy of the “objective historian”, the best hope of George Santayana’s famous quote: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Tyrion says as much:

He is our memory. The keeper of all our stories. The wars, weddings, births, massacres, famines. Our triumphs. Our defeats. Our past. Who better to lead us into the future?

I was immediately reminded of the 1995 film The American President—not just because the small council scene was, as Joe Reid pointed out at Primetimer, very Sorkinesque indeed. I was reminded of this because both Game of Thrones and The American President (wherein the President is a former history professor) imagine a better world that comes when an historian is given the seat of power.

The problem with this idea—that an objective historian can know the way forward—is similar to the problem with Brienne’s flattening of Jamie’s story. There is no such thing as an objective historian. Even someone like Bran, who can see events as they happened, would be left to guess at the inner lives of those involved, and required to editorialize about the thorny questions of who was in the right, and what the future ought to hold.

It also plays into the hands of a wider problem in our culture: the cult of objectivity. “Big Data” is touted as the solution to our problems. STEM education is promoted as superior to other fields. In fringe online communities, especially the self-described “alt-right” or “Men’s rights activism”, there is a feverish rejection of postmodern subjectivity in favor of an “objective truth” that they can reach by way of their “reason” and which they can access by virtue of being “rational” people. This is typically a convenient mask for their position as (typically) white (typically) men; they do not have to confront their prejudice and privilege, because they are the only ones being rational and objective (contrasted with those “irrational,” “emotional” women and people of color).

History doesn’t work like that, I’m afraid. History—even if we could see it played before our eyes—is inherently a subjective interpretation of competing accounts of subjective people interacting with other subjective people in subjective ways. Historians use their subjective judgement to decide what and who are subjectively important and what and who are not. It’s subjective all the way down.

That does not mean that the histories that they write are not true. But it is a folly of our current moment to assume that just because something is subjective, that it is not true—and that because something is objective, it cannot be false.

If Bran Stark did exist, I would not want him anywhere near the throne. That both George R.R. Martin and the showrunners seem to have fallen for this idea of crowning a mythical “objective” super-historian is, for this historian, very disheartening indeed.

So… Who Won?

So, who won the Game of Thrones? In the end, it ultimately didn’t matter much—both within the world of the story and also for the viewers. Because as in actual history, the stories of the wars that were fought and the people who rose to power is often far less interesting than the journeys of the flawed, complicated, and beautiful people outside these grand narratives. It was initially surprising to me that so much of the final episode of Game of Thrones was about history itself. At the end, it was similar to the musical Hamilton, with its recurring theme of: “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?”

Tyrion, Brienne, and Bran all can teach us different lessons about what history is, what it is not, and how to treat historical texts. I can only hope that the next smash-hit historical epic (whether fantasy or not) embraces history in an even better way.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.