This is Part 17 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Marta Cobb. You can find the rest of the series here.

Women in power are all over the news. Joe Biden has chosen Kamala Harris as his running mate for the 2020 US presidential election. Leaders such as Angela Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, and Tsai Ing-wen are being praised for their effective response to COVID-19 in Germany, New Zealand, and Taiwan respectively.

And yet, today fewer than 7% of heads of state are women. The 2020 Democratic primary in the US featured several qualified women. But Joe Biden won the nomination, polls suggest, because some voters believe that a man has a better chance to defeat Donald Trump. A recent study by Lucina Di Meco, Global Fellow at The Wilson Center, suggests that the women Democratic candidates in the primary were more likely to be attacked on social media. And more, as Suyin Haynes at Time magazine found, the report shows:

that social media narratives around female candidates were more negative and focused on issues of character and identity, rather than electability or policy.

The campaigns of high profile female politicians like Hillary Clinton are often dogged by rumours, scandals, and conspiracy theories (some of them highly dubious—remember Pizzagate?) that were ignored or tolerated in their male opponents.

This is not limited to politics. Women in the workplace regularly have to fight to be heard and have their contributions acknowledged. They have to modulate how they speak to make sure they are not seen as “aggressive,” “shrill,” or “bitchy.” And they are still regularly excluded from positions of power in most religions.

Simply put, women are held to a different standard of behaviour. And misogynistic fears of women pursuing leadership roles is nothing new; it would be very recognizable for those medieval women who pursued leadership roles in the Church.

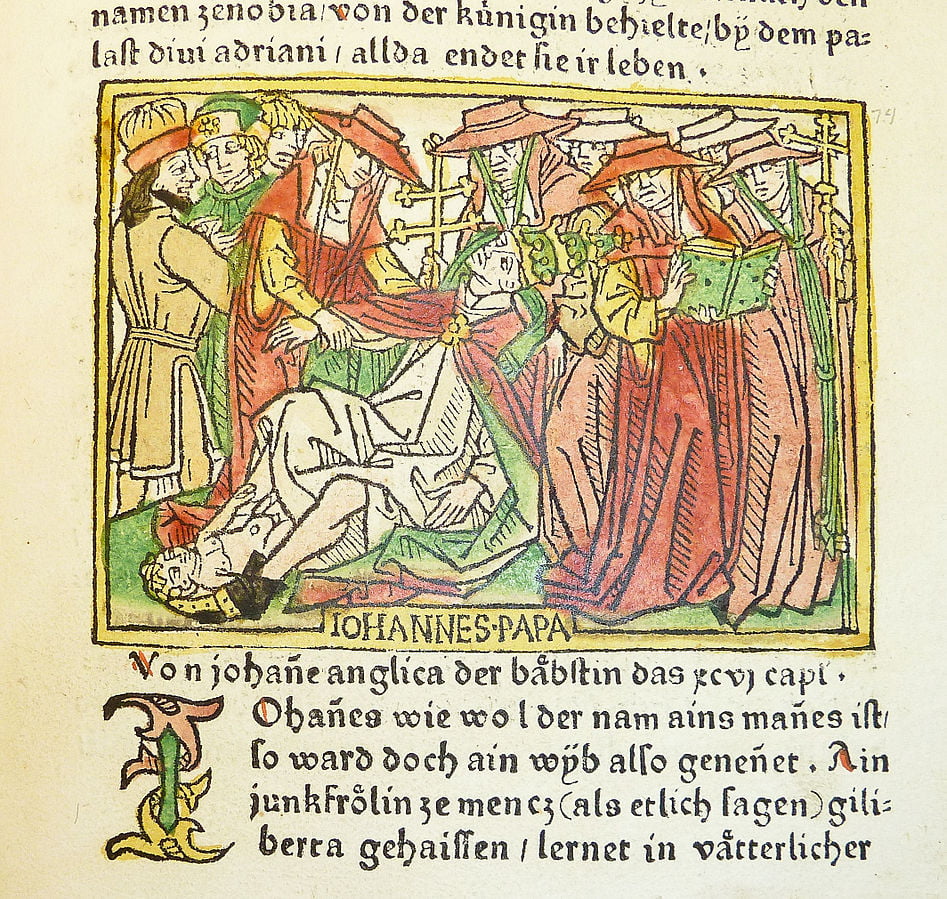

How Pope Joan Petrified the Patriarchy

One example that illustrates this problem clearly, is a legend first recorded in a 13th century chronicle, the Chronica Universalis Mettensis. It that tells a tale of a ninth-century woman named Joan who briefly became Pope. We have no reason to believe this story is true, but many medieval people did. According to the story, to follow a lover, Joan disguised herself as a monk. Eventually, she rose through the church hierarchy, becoming first a cardinal and then elected Pope. Unfortunately for her, she became pregnant. Her identity was finally revealed when she went into labour during a public procession. Shortly afterward, according to the story she died. Different versions of the story vary on how: some say it was due to natural causes, some say she was murdered, or and some even say she was stoned to death by an angry mob.

Although the story of Pope Joan is now understood to be a fable, for centuries, it was widely believed. It inspired multiple retellings in the later Middle Ages and beyond.

In 1601, Pope Clement declared that the legend was not true. The veracity of the tale, however, isn’t as important as what stories like this reveal about the degree to which people feared women in positions of power. This was especially true within the Catholic Church, where women could not (and still cannot) become priests, let alone the pope. Then, as now, this is rooted in the misogynistic belief is that women are somehow inherently unfit to lead.

Women: The Devil’s Gateway?

The medieval Catholic Church was uncomfortable with the women who strove for power and authority. This is despite the fact that women played an important role in the early church and in bringing Christianity to Europe during the early Middle Ages. The Bible indicates that women were amongst the earliest followers of Jesus. Over the following centuries, queens and other noble women often encouraged their husbands to accept Christianity, which in turn led to its promotion within the wider population. Yet, despite this, women were barred from the priesthood.

The Catholic priesthood has always been made up of men, but priests have not always been celibate. Prior to the 11th century, priests could, and did, marry (though they were discouraged from doing so more and more as time went on). In the 11th centuries, the practice was officially banned. This resulted in women being increasingly shut out from anything resembling clerical authority.

Before the reforms the priest’s wife would have a special role within the parish. Afterwards, women who lived with priests were no longer considered legitimate wives. Women could take up a religious life by becoming cloistered nuns, but if they did, they were expected to remain within their convents rather than have any significant influence in the wider world.

Theological writings of the period, most of them inevitably written by male clergy, reveal that women were often considered physically, intellectually, and morally deficient. Moreover, according to these writings, they were especially vulnerable to spiritual invasion by demonic forces. For example, the theologian Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240) describes women as “the Devil’s gateway”. Later writers continued along these misogynistic lines. According to inquisitors Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger in the notorious witch-hunting guide Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches, 1487), “women are naturally more impressionable, and more ready to receive the influence of a disembodied spirit.” This is one of the reasons why women were more likely to be accused of being witches in the late medieval and early modern period.

Medieval Women Breaking the Glass Ceiling: ‘Creativity in the Face of Constraints’

It’s important to acknowledge the limitations medieval women faced in their religious and secular lives. But it is equally important to show how they pushed against those boundaries. Katherine L. French characterises women’s religious experiences in the later Middle Ages as “creativity in the face of constraints .” In spite of the obstacles they faced, some women managed to create new roles and new ways of gaining spiritual authority for themselves. They did this not by pretending to be men, but by being themselves.

For some women, they took the stereotype that they were vulnerable to “disembodied spirits” and turned it on its ear. They said that this also made them more open to divine influence. Thus they made this alleged “weakness” a form of strength, and sought a form of intimate contact with God, Jesus, or other holy figures. And in seeking these mystical religious experiences they also recorded their experiences for the benefit of themselves and others. If a woman could persuade others that she spoke or wrote the words of God—not always an easy task—then she could become a source of religious authority.

Some of these women became enormously influential as a result of their visions, both in their own day and long after their deaths. For example, In the 14th century, Bridget of Sweden became famous for her revelations. She had a series of visions in which Jesus acknowledged her as his bride. In her writing, she portrays herself as a willing vessel for his words, but in her life, she was anything but passive. She founded her own religious order, successfully campaigned for the pope to move back to Rome from Avignon, and travelled extensively. She was declared a saint in 1391, less than 20 years after her death.

Two centuries earlier, Hildegard of Bingen, a nun living in what is now Germany, experienced a series of visions from a young age that were eventually recorded in the book Scivias (Know the Ways)—one of Hidegard’s many works. Hildegard was quite famous in her own time. She travelled widely on preaching tours (at a time when women usually weren’t allowed to preach). She corresponded with kings and popes. Hildegard’s legacy is a long one: her musical compositions are still frequently recorded and performed in early music circles. She was canonised (i.e. declared a saint) and named a Doctor of the Church—one of the highest honors possible for Catholic saints—in recognition of the contribution she made to the Church through her extensive writings. But this was only done in 2012, over 800 years after her death. And she remains one of only four women to receive this distinction, proving that the modern Catholic Church still is painfully slow to acknowledge women and the roles they play.

And perhaps the most famous woman from the Middle Ages was also one of these visionaries. Joan of Arc was inspired by visitations from Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret. She famously became a military leader, led the armies of France to victory against their English opponents, and helped to bring about the end of the Hundred Years War. Joan was canonised in 1920, was declared the patron saint of France, and her life is the subject of countless books, plays and films.

Were These Medieval Women Saints or Heretics?

Jules Eugène Lenepveu.

And yet, we know that Joan was burned at the stake. One person’s saint can be another’s heretic. “Heresy,” especially in the Middle Ages, was a serious accusation: that you held or promoted beliefs that contradicted Church teachings. But, then as now, when women come under scrutiny it is often because they are behaving in a way that men do not like rather than for anything truly “heretical” in their beliefs. When Joan of Arc was captured by forces loyal to the English, she was tried and burned as a heretic in 1431. Famously, in her trial she held her own against a panel of highly learned inquisitors and the many accusations they made against her. Surviving records reveal that her accusers returned again and again to the issue of her wearing men’s clothing and actively participating in warfare—behaviour that led to her execution.

More than a century earlier in 1310, another mystic, Marguerite Porete, was also executed for heresy. Her crime was writing and then circulating a work inspired by her visions: The Mirror of Simple Souls. The Mirror of Simple Souls had been condemned and burned by the inquisition, but Marguerite continued to speak and teach publicly.After her death, however, The Mirror continued to circulate anonymously or under the name of other authors without controversy. This suggests that the text’s content was not the problem. The problem was Marguerite herself. Her refusal to submit—in other words, her persistence—was the real problem.

Margery Kempe, an English mystic living in the late 14th and early 15th century, was also accused of being a heretic. According to her autobiography, The Book of Margery Kempe, she was frequently arrested, imprisoned, questioned, and threatened with burning. Her religious beliefs were actually quite conventional: unlike the Lollards, an English heretical group of which she was often accused of being a member, Margery wanted to attend confession and take holy communion as often as possible. The real problem is that her behaviour, although motivated by religious belief, was unruly, sometimes to the point of causing civil unrest. She wept loudly when anyone or anything reminded her of Christ’s suffering (which happens in her book a lot). This made her a disruptive presence, especially in church. She talked frequently about religious matters, which led to accusations that she was preaching. As I mentioned above, preaching was not usually allowed for women— especially not for lay women.

Margery also refused to dress conventionally. She wore white clothes to symbolise her status as a born-again virgin, a rejection of her previous role as wife and mother. And perhaps most galling to religious authorities, she let Jesus decide which members of the clergy she would obey, and which she would not. Instead of joining a convent or becoming a holy recluse, she travelled widely—to Rome, Jerusalem, and other pilgrimage sites. But she inevitably annoyed her fellow travellers with her excessive piety. They might be on pilgrimage, but they didn’t want a sermon during every mealtime.

In parallel with the accusations and conspiracies levelled against prominent women today, Margery also continually encountered malicious rumours about herself. These often were accusations of supposed sexual or religious hypocrisy, which were designed to undermine her reputation as a chaste holy woman.

Margery deliberately courted controversy. So, during her life and in the years after her death she was not first in line for sainthood. She didn’t receive much recognition until her writings were rediscovered in 1934. Even now, scholars debate whether she was an important mystic, a wannabe saint, or a neurotic. Her “bad behavior” in the eyes of others continues to be used against her.

Well-Behaved Medieval Women Seldom Made History

It is often said that “well-behaved women seldom make history.” In the later Middle Ages, women could use their connection with the divine as a way to justify unorthodox behaviour. This could include writing a book, preaching, or wearing armour and leading an army. But belief in their own divine approval could only take them so far. Ultimately, they needed to be accepted by the secular and religious authorities, which meant, to a certain extent, they had to conform to models of belief and behaviour that their contemporaries could tolerate. And yet, in spite of great difficulties, these women managed to make their voices and experiences heard in their time and our own.

Self-made influencers like Oprah Winfrey or Kim Kardashian can be seen as the modern equivalents of Hildegard of Bingen or Margery Kempe. Although they lack the power that comes from having an official position in the political or religious spheres, the amount of ‘soft power’ they wield should not be underestimated.

Yet, in regards to our attitudes towards women and more formal roles of authority, far less has changed than we might like to think. In the 21st century, women are still much less likely than men to hold official positions of power, whether in politics, religion, or business. Women in power, or seeking power, are far more likely to be judged by their personal appearance or “likeability” than their experience or qualifications. They are held to a far more rigorous standard of appropriate behaviour than their male counterparts. Until we dismantle these misogynistic double standards, our society will remain far more “medieval” than we’d like to admit.