This is Part 9 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Megan Arnott. You can find the rest of the series here.

During the 2018 Super Bowl, Dodge ran commercials for the Ram truck. In them, a group of Vikings use the truck to haul their ship. They sing a heavy metal version of “The Wheels on the Bus” (replacing the word “bus” with “truck”); the ad proclaims, “There’s tough, and then there’s Viking tough.”

The target audience for truck ads are typically men. In order to appeal to their target audiences, ads sell you an idealized image of yourself—as ad-man Don Draper said in Mad Men:

You are the product. You feel something. That’s what sells.

Notoriously, ads use gender stereotypes to construct images of who the consumer could (and should) be. Truck ads sell the image of a rough, hard-working man who wants something that allows him to be a rough, hard-working man—and confirms his masculinity along the way. Typical ads use cowboys, farmers, soldiers, other machines, and large mammals like bears, bulls, or rams. But they’re not marketing to cowboys, farmers, soldiers, or brown bears—at least not exclusively. They’re marketing the idea that you, you, can be as tough, as manly, as powerful as them.

Vikings are a perfect fit.

Vikings and other “medieval” men are used in advertisements as visual shorthand for a masculinity that is synonymous with strength. In advertising, this kind of unchecked masculine strength is rarely presented as something negative or dangerous. Instead, it’s a promise: buy this product, and your manliness is confirmed. Your sexual potency is confirmed. You will be who you want to be: medieval.

Manly Medieval Men

There are many images of the medieval in the popular imagination. And every ad that uses the Middle Ages uses a specific version of the Middle Ages (usually tied to medieval fantasy) that is popular in that specific moment.

One of the most potent images over the past thirty years is the image of strong male warriors—kings, knights, or Vikings. One of the ways in which this medieval masculinity is sold to modern men is by selling men’s virility as part of masculine communities. In this model of masculinity, men are meant to claim their virility by being in the companionship of other men, as in a fraternity of knights. Courage, bravery and camaraderie are thus coded as explicitly, and sometimes even exclusively, masculine strengths.

A prime example of an ad that exploited this popular image comes from the late-Reagan/early-H.W.-Bush era; a series of commercials equated the United States Marines with “medieval” knights. In the commercial, titled simply “Knight,” a voice-over proclaims:

Once, there were a few, proud men. Men of adventure. Men of courage. Men who knew the meaning of honour. There still are. The few, the proud, the Marines.

A king holds a sword aloft, and lightning crackles from it. A knight rides up to him, dismounts and kneels. The king dubs the knight with the sword, lighting arcing to his shoulders. As he does, the knight morphs into a US marine in full dress uniform. In this version of the commercial there is also a boy who looks on while the man in armour is knighted; the boy is inspired to be this kind of man—he looks up to him.

This ad evokes both the actual Middle Ages and also the fantasy neo-medievalisms of the 1980s (think He-Man, Highlander, Excalibur, and all the legacies of Dungeons & Dragons) with the lightning bolts that emanate from the sword. The “knights” in this ad defend the “kingdom” of the United States; it equates aristocratic warrior-elites with contemporary professionalized military service through oblique references to chivalry and honor.

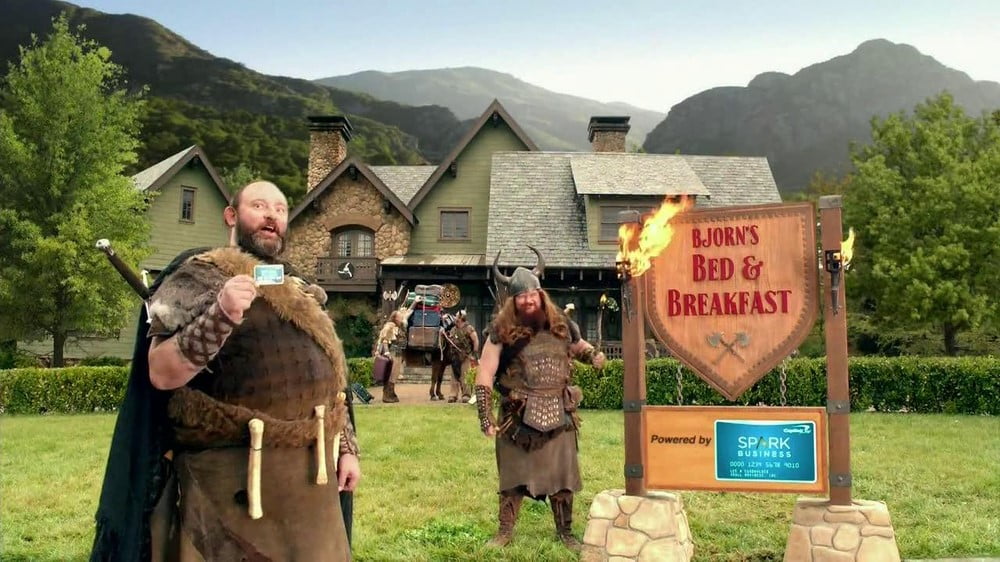

But medieval men need not be chivalrous or honorable to be sold in modern ads. One of the most notable “medieval” campaigns of the last ten years has been the “What’s in your wallet” Capital One Vikings, who appeared from the late 2000s into the mid 2010s. Originally, the Capital One card kept the hordes at bay, but eventually, these Vikings were the ones literally armed with the Capital One card.

In the beginning, your ability to wield wealth is equivalent to wielding enough strength to stop an oncoming fight—but not just a normal fight, a fight with ravenous, pillaging Vikings! Here, the man watching the ad is not meant to identify with the Vikings so much as he is expected to feel confident in his ability to weather any financial storm (and maybe laugh a bit at the absurdity of it all). But as the ad campaign went on, the ad company put the Vikings front and center. So, they created a new twist—these strong, violent men do the same things that you do! They go to family gatherings; they go shopping; they go on vacations to New Orleans or the Grand Canyon. The Capital One card has made these men at least half-civilized, in a transformation almost as radical as the knight-to-Marine. And this slightly-kinder and gentler masculinity was all thanks to a credit card.

Medieval Sex Sells

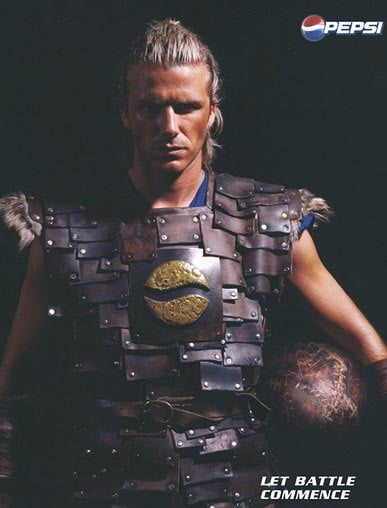

In another example, in 2004 Pepsi used legendary British soccer player David Beckham in a commercial which made liberal use of medieval imagery. This commercial was generated by a certain cultural moment: The Lord of the Rings trilogy had been a cultural phenomenon for the past three years, King Arthur starring Clive Owen would be released the same year, and the Crusades film, Kingdom of Heaven was due to be released the next year. The medieval epic was having a moment.

Each of these movies centre around masculine communities or brotherhoods. The same can be said of the commercial. In it, armed guards enter a medieval-looking town square and proceed to gather all the Pepsis, placing them in a large cart to take them away.

While escaping, a young boy loses the ball he had been carrying. Enter David Beckham and his team of soccer players. They then proceed to what can best be described as “soccer fight” the armed guards—one player shoots past a row of guards to hit the lock on the cart with the ball, freeing the Pepsis for everyone. In this commercial, the imagined medieval battles of yesterday are equated with the organized sports of today with the catch-phrase “Let Battle Commence.”

The ad has little to do with cola (except maybe to say that it’s a valuable treasure captured by a Robin Hood-type). What’s really at issue here is the association of medieval warrior manhood with it. David Beckham and his crew are a modern fraternity of knights going into battle, and although odds are stacked against them (they wear inferior, but way cooler, armour), they are so much stronger than their opponents that they can literally run circles around them. The implication is that soccer players are like medieval knights or Robin Hood’s men, in that they are a brotherhood of unstoppable warriors.

The presence of the boy in the ad, like in the Marines commercial, is a signal that this is also a version of manhood to be emulated and passed down—and one that inspires admiration from your children (or if you are a child, one worth looking up to). The use of David Beckham as the central figure also makes the connection between male strength and male sexuality more explicit. These men are not just cool, they’re hot. They are sexually desirable, strong and brave “knights,” committed to a team or martial brotherhood. This ad forges knights and soccer players into poster-boys for virility—and virility is what Pepsi wants you to associate with its product.

The most obvious and explicit conflation of “medieval” with male strength and male sexuality is the Durex Pleasure Ring commercial, “Be Heroes for the Night.” In it, a sexily rugged man and woman dressed in rough medieval garb travel over harsh but beautiful terrain. They meet in a barn and immediately fall into each others’ arms. As they do, she reaches for a box of Durex, and as they roll around on the medieval furs in front of a roaring fire, they instantly transform into their modern-day selves.

This commercial takes advantage of the current popularity of television shows like Game of Thrones or The Vikings, appropriating their hair styles and fashions in particular, to sell a sex product to its customers. The ad simply sells the titillating fantasy of rough-and-tumble medieval sex so often seen in these shows.

Sex—at least good, consensual sex—has not always been part of the popular perception of the Middle Ages. So the Durex ad is a reminder about how much sex is a part of those shows, and of our current concept of the medieval. In these shows (and in the ad), virility is still in the realm of men, but women are impacted by it in different ways—some of the most-famous sex scenes in these shows are not consensual or good sex. Of course, the commercial is just a reference to the sexiness of the shows, not the problematic depictions of sex these shows often contain—or the ongoing discussions about the destructive force of the unchecked (particularly male) sexuality that they portray. This commercial is a partial indictment of the complexities of the sexual encounters in shows like Vikings and Game of Thrones—it shows that often the main thing the audience takes away is simply the sex.

Medieval Men Rule!

The image of a court of men, like King Arthur’s court, is a shorthand that is often used in advertisements as well. This use of the Middle Ages harkens the audience’s mind back to an imagined time of unchecked male power and authority. For example, about 10 years ago, there were a series of commercials for Miller Lite where men from different walks of life (representing different areas of pop culture) came together and collectively decided on “Man Law”. This included football player Jerome Bettis, pro wrestler Triple H, comedian Eddie Griffin, adventurer Aron Ralston, professional bull-rider Ty Murray, and—acting as their “King Arthur” type—Burt Reynolds.

These commercials declare that these are the “Men of the Square Table,” who sit around and pass decrees on “man things,” like male sovereignty over the garage fridge (which should only be for beer) or when it is okay to ask out your buddy’s ex-girlfriend after they have broken up.

These ads are clearly attempting to tap into feelings of male grievance against the perceived advances of feminism and place them as part of the age of the “bro” sub-culture—as promoted by figures like Barney Stinson on How I Met your Mother and “the Bro Code.” In it, these men are acting as a fusion of Arthurian court and board room, unilaterally (and of course, with no female input), passing decrees on what appropriate behavior for men should be. And facilitating this meeting, which is the pinnacle of a perceived, subversively unchecked male power, is Miller Lite beer.

10 years after the Miller Lite ads, Bud Light launched the “Dilly Dilly” campaign, which sees Bud Light being shared around a more literally “medieval” court. These advertisements also include references to its previous campaign, the “Bud Knight,” with a tagline “Here’s to the friends you can always count on.” We can see differences in the way masculinity is constructed in different cultural moments, but it is still trying to sell audiences a concept of masculinity to go with their beer. Both beer campaigns were slotted to be shown during football games and use camaraderie as their main selling point, particularly masculine camaraderie. The Miller Lite ads were specifically about male camaraderie, whereas the medieval imagery in the Bud Light commercials, just like in the Viking Dodge Ram truck ads or the Durex ads, doesn’t necessarily exclude women.

But the focus is still on masculinity, particularly a martial or virile masculinity. In this case, and in many more recent examples, masculinity does not have to mean a life that women can’t participate in. But men are always the majority of the central figures: the heroes, the kings, the knights. Though women may be present, the focus is on male figures—when they are not objects, women should be participating “as one of the boys.”

Even when masculinity, toughness, or camaraderie is not the main purpose of the medieval imagery, as it is in these beer commercials, it is interesting which “medieval” images are chosen. An Intel commercial from 2012 also uses this imagery of the King’s court—but instead, it is meant to show that the technology they were using before the Intel computer comes in is old-fashioned.

Yet, even this equates a business meeting with the meeting of a king and his knights. The king and his court struggle with the new technology. It is a female employee (there are two, one already in armour, the one with the new computer in modern dress) who brings the new Intel technology to shake them out of their old ways. Women are a disruption of male power—even if that disruption is ultimately couched as a positive one.

Which Middle Ages Get Sold?

Medievalists.net compiled a list of the top 10 “medieval” commercials. What is apparent from this list is that Vikings and knights (as opposed to, say, prioresses, bishops, merchants, peasants, brewers, monks, or any other visions of medieval men and women) dominate how the public recognizes the medieval. What is also clear is that the medieval images are much less about the Middle Ages themselves than they are about contemporary trends in both masculinity and representations of the “medieval.” These are the men that contemporary men want to be—or at least, that ad companies want them to want to be. In many ways, “medieval” continues to be shorthand for “masculine”—but a very restricted concept of “masculine.”

Advertising sells you an image of yourself, improved by their product. To give the consumer an image of virile manhood, one of the options is to use medieval—or better yet “medieval”—imagery. The commercials are from different eras and, hence, show how our ideas of virile masculinity have changed. And as made apparent in the recent controversial Gillette ad, our concepts of masculinity are changing every day. Yet, without having to do too much to explain, a reference to a medieval image of a knight or a Viking are still potent ones, and help advertisers quickly evoke the feelings of being a strong, virile man. If you too want to be as tough and sexually appealing as a Viking, it is up to you whether you think that you will need a pleasure ring, a truck, or a credit card.

Editorial Note: Paul B. Sturtevant contributed to the writing of this article.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.