Part XXXVIII in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Sarah Randles. You can find the rest of the special series here.

Medieval Christians did not care what race the Virgin Mary was.

That comes from the blog of Professor Rachel Fulton Brown, medievalist at the University of Chicago. While we here at The Public Medievalist try not to weigh in too heavily on active academic debates, this time, we’ll make an exception. The reason is that her article was snarkily titled ‘How to Signal you are not a White Supremacist’. Professor Fulton Brown appeared to be arguing that the Middle Ages could not be used to support modern white supremacism, because medieval people were not racist.

We here at The Public Medievalist have taken some rather great pains in the past nine months to uncover the answer of the deceptively simple question ‘Were medieval people racist?’ The answer has been, as they almost always are with deceptively simple questions like this, ‘it’s complicated’. But in that complexity, the answer is certainly not a simple ‘no’.

To briefly summarize her argument: Fulton Brown’s chief evidence is the stained glass window above, known as the Belle Verrière, at Chartres Cathedral. Fulton Brown interprets the figure at the centre as a dark-skinned Virgin Mary. She implies that this means medieval people understood the Virgin Mary as a dark-skinned Jewish woman. And thus, they cannot be racist.

This is not true; in that particular image Mary does not have dark skin, medieval European Christians did not generally think of her as dark-skinned, and many medieval people were racist (though race and racism were very different then).

There is a bigger question, however. Did medieval European Christians think of biblical characters—especially figures like the Virgin—as Jewish or dark-skinned? And what does that mean about their perception of race?

A Look at the Evidence

Thankfully, Marian at Mostly Medieval has already shown that the face of the Virgin in the Belle-Verrière was not originally intended to be dark. But I can show you why: the ‘close up’ photo of the Virgin’s face that Fulton Brown posted is from a Wikimedia photo taken by Hans Bernhard in 1964. After 1964, Belle Verrière underwent both restoration and cleaning; the glass had its patina of age removed, and its cracks were fixed. As you might guess, the Virgin’s face is now much lighter, as noted by Marian in her blog post. You can see the results in this detailed photograph by Dr. Stuart Watling (right).

So, this Virgin Mary in Chartres wasn’t dark-skinned, just dirty.

And moreover, she’s not even medieval. As Marian noted, a restoration was undertaken in 1906, which replaced the previous glass—which was itself a restoration of unknown date! The brown mottling still evident on the panel as it has been restored today suggests either that it underwent the same browning corrosion which affected the medieval glass, in a process which accelerated in the twentieth century, or that the 1906 restorer attempted to replicate the damage already evident in other medieval glass in the cathedral.

Marian has also pointed out that the Virgin’s face, in its current state, is no darker than many of the other faces in the medieval stained glass at Chartres. To this I’d add that there are many figures at Chartres with a brown skin tone where there is no biblical precedent to suggest they might have been intended to represent Jewish or sub-Saharan African people. Even a scene from the “Miracles of the Virgin” window (believed to depict the parishioners of Chartres pulling carts to assist in the rebuilding of the Cathedral), shows people with a range of different skin tones, including some which are as dark as the cleaned version of the Virgin’s face in the Belle Verrière.

Simply put, we can’t know the original colour of the Virgin’s face in the Belle Verrière, but there is no evidence that she was ever intended to be depicted as having dark skin. Judging by the colour of her face in the many thirteenth-century windows at Chartres, it seems it would have been exceptional if she had been.

However, Mary was associated with an Old Testament text from the Song of Songs which reads:

I am black, but beautiful.*

[Nigra sum, sed formosa. Song of Songs 1:5]

These lyrics were commonly sung as a short refrain (called an ‘antiphon‘) in the feasts of the Virgin. But despite the association of the Mary with the ‘nigra sed formosa’ woman of the Song of Songs in Liturgy, I do not know of any depiction of the Virgin Mary as dark skinned in stained glass, or, for that matter, in any manuscript illuminations, wall paintings or embroidery.

In only two media in medieval art does the Virgin appear, at least on the face of it, to have been depicted with dark skin: wooden statues common in Western Europe, especially in France from the twelfth century onwards, and later, icon-like paintings to the east.

Hundreds of medieval black Madonna statues have been found in Western Europe, many of them venerated as cult objects at various times during the Middle Ages and beyond. However, it remains a subject of debate as to whether individual statues were originally intended to be black, or whether they have become so over time (by either being painted or losing their paint). For example, the famous black Virgin of Montserrat (right), and the Notre-Dame du Pilier statue at Chartres have recently been shown to have originally had much lighter skin tone.

The blackness of these statues and images became an essential part of why and how they were used in worship. However, this does not necessarily mean that that the blackness of the statues was ever clearly associated with the idea of dark skin or that the people who venerated them thought that the Virgin Mary herself had dark skin.

Was Mary Jewish?

So if she was not depicted as dark-skinned, was the Virgin Mary depicted as Jewish? This is a more difficult question to answer. In medieval Christian art, Jewish men are usually denoted by the Judenhut (Jewish hat), sometimes by long beards, and frequently by anti-Semitic caricatures. But there is no standard way that medieval Europeans depicted Jewish women. Often they were portrayed in a way that does not mark them as different from Christian women—including showing no difference in skin tone. When they are depicted with negative stereotypes, they are depicted as sexually promiscuous. Obviously the Virgin Mary isn’t going to be depicted that way.

There are a few pieces of medieval art where Mary is shown unequivocally as Jewish. Those typically depict the Presentation of the Virgin to the Temple, an event which takes place in Mary’s childhood (but only in the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James—which was, essentially, a New Testament prequel).

In these images Mary’s Jewishness is implied by the context, rather than in her dress or body. In fact, Jewishness was rarely associated with dark skin in medieval Christian art–it is likely that medieval Christian artists, especially those in Northern and Western Europe, were familiar with Jewish people in their own communities who likely did not necessarily have darker skin.

While medieval Christians, including artists, understood intellectually that Christ and Mary were both Jewish and from the Middle East, this was of not something that was generally emphasised in medieval art. And in the case of the Virgin, at least, there was no visual language of difference that could indicate that she was Jewish.

People of Colour in Medieval European Art

Even though the Virgin was not depicted as a person of colour, many people of colour are depicted in medieval images—if you want to explore some, see the excellent series The Image of the Black in Western Art, or the popular Tumblr site People of Color in European Art History.

It is clear that over the course of the Middle Ages, there was a developing tradition of depicting blackness in medieval European art. But why, if the Virgin Mary was associated with the ‘nigra sum sed formosa’ text, did medieval artists not depict her as a sub-Saharan African woman? Was it because dark-skinned people were unknown to the artists?

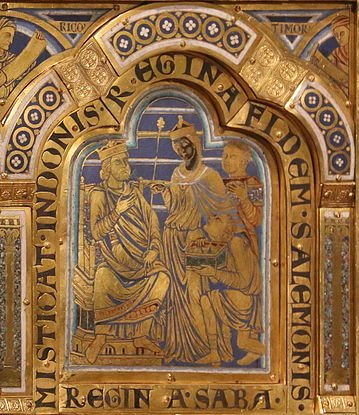

In twelfth-century Western Europe when the Chartres windows were made, images of sub-Saharan African people were rare. But they become more common in the later Middle Ages, reflecting increased contact between people of different cultures. While the ‘nigra sum sed formosa’ text was used in medieval liturgies which celebrated the Virgin Mary, it was also associated with the Queen of Sheba, who is depicted as dark-skinned in some medieval works of art from the twelfth century onwards.

However, in other works, the Queen of Sheba is depicted with light skin, as in one late-twelfth-century window at Canterbury Cathedral. In one fifteenth-century manuscript (right) she was originally depicted as light skinned, with blonde hair, but her skin was overpainted by a later illuminator, suggesting that the later artist was aware of conflicting models for depicting the Old Testament queen.

It seems, then, that in spite of being familiar with the use in liturgy of the ‘nigra sum sed formosa’ text that associated the Virgin Mary with the ‘black but beautiful’ woman of the Song of Songs, medieval artists actively chose to depict her with light skin—at least in the vast majority of Western European medieval images.

Medieval Whitewashing?

Should this then be interpreted as evidence for medieval racism? Were medieval Christian artists deliberately whitewashing a woman they believed to have dark skin in order to recreate her in their own image?

For the most part, medieval artists depicted the Virgin and other biblical characters in clothing and settings which mirrored their own—although that changed a bit in the later Middle Ages, when some artists attempted to historicise biblical depictions. But this does not mean that the practice of depicting Mary as a medieval European light-skinned woman was intended to remove an existing understanding of Mary as a person of colour from the visual record.

Medieval artists did not inherit a tradition of depicting the Virgin with dark skin. The ‘nigra sum sed formosa’ text from the Song of Songs was not necessarily understood literally. Like other Old Testament texts, it was interpreted typologically—as prefiguring the New Testament—and may never have been understood as meaning that the Virgin had dark skin. Although some of the black Madonna statues have been inscribed with the text from the Song of Songs, more research needs to be done to determine whether the inscriptions were made at the same time as the statues, or whether they were added later (perhaps to explain the colour that the statues had become over time).

Moreover, dark skin did not always have negative connotations for medieval Christians. The black magus at the Nativity and St. Maurice were understood to be sub-Saharan African people, and they were revered figures in the later Middle Ages. But as other contributors have explored in their articles in this series, some medieval European thinkers did equate blackness with evil. Like I said at the beginning of this article: it’s complicated. Not all medieval Europeans believed the same things.

Nonetheless, in creating the Virgin and Christ in their own image, medieval Christian artists, perhaps unwittingly, produced a visual world where people of colour were clearly framed as other. In doing so, they may not have been racist in the modern sense, but the legacy of their imagery was centuries in which the Virgin and Christ were made white.

For Further Reading

Chantal Bouchon, ‘Un vitrail emblématique: Notre-Dame de Belle-Verrière’, in La Grâce d’une Cathédrale: Chartres, ed. Michel Pansard et al. (Strassbourg: Nuée Bluee, 2013), 217–21.

* Editor’s Note: The original translation of the ‘Nigra sum sed formosa’ text is considered by many scholars to actually be a mistranslation into Latin from the original Hebrew, which should more-accurately (and less-pejoratively) read ‘Nigra sum et formosa’, or, ‘I am black and beautiful’. That being said, it does seem as though the medieval church used the original ‘sed’ mistranslation. For more on how this one word can change the entire meaning, have a look at Kate Lowe‘s article on the topic here.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.