This is Part 13 of The Public Medievalist’s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Megan Cavell. You can find the rest of the series here.

There were women writers in the Middle Ages. But they’re not household names. I myself didn’t know the name of a single female writer from my field of study—early medieval (or Anglo-Saxon) England, from roughly CE 600–1100—until my PhD was well underway. That fact still shocks me. But I think it can be partly chalked up to the fact that most women writing in this period were using Latin.

My own research is on the Old English poetry produced alongside Latin works in this period. Because of the way this poetry survives (in far too few manuscripts), I deal mainly with anonymous texts. These are almost always assumed to have been written by men. While elite, aristocratic and ecclesiastical men certainly dominated literary culture during the early medieval period, they were in no way the only writers at work. Once you hear about the fascinating women pushed to the margins of this literary canon, there’s simply no turning back. I want to know about them all, and I want to share that knowledge with every person I meet.

Every.

Single.

Person.

And so, I interviewed Diane Watt, professor of medieval literature at the University of Surrey. Diane is currently undertaking a project funded by the Leverhulme Trust called “Women’s Literary Culture Before the Conquest.” I set out to learn what light her project will shed on this important subject.

Megan: Can you tell us about one of the woman writers you’re researching?

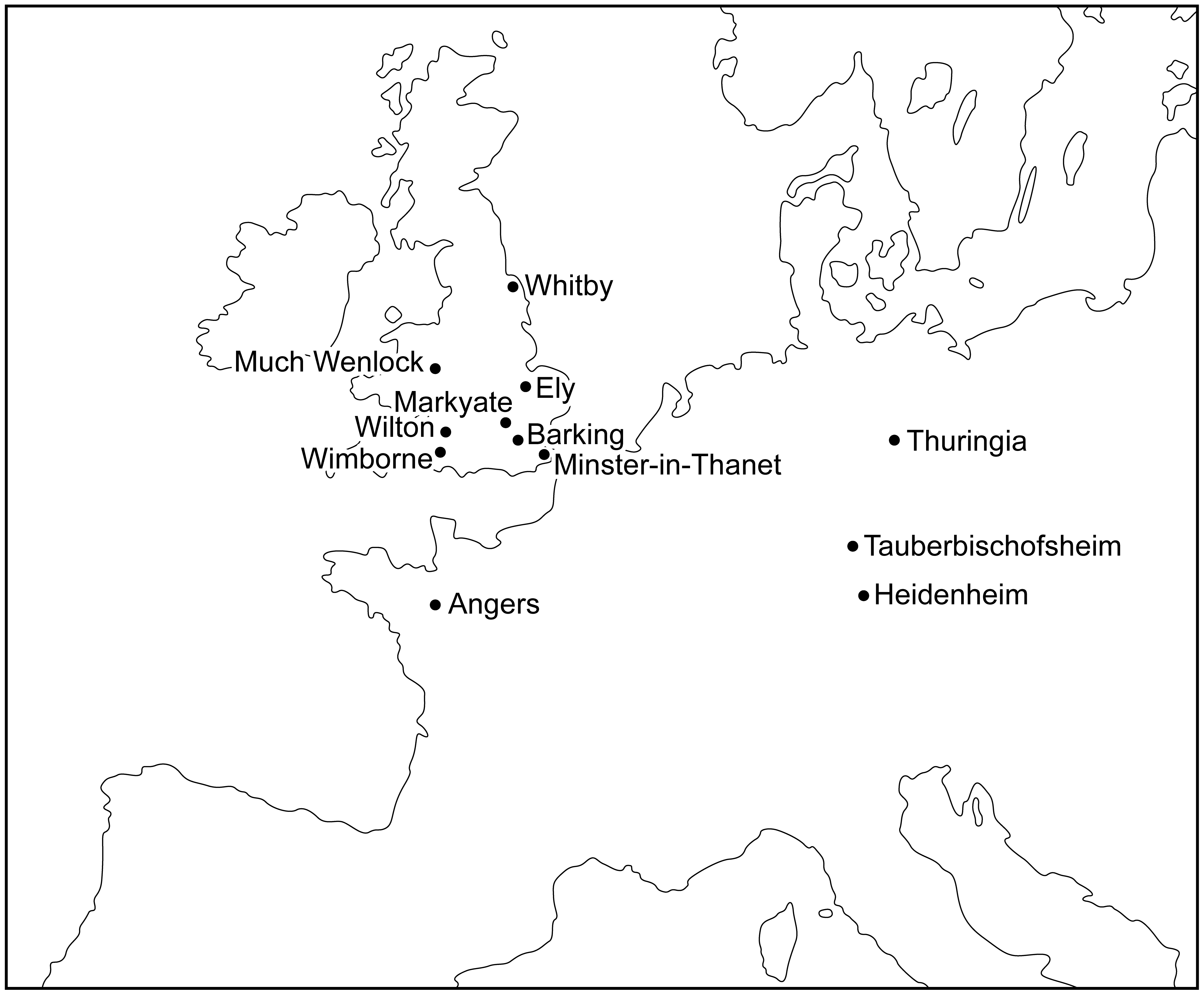

Diane: Well, the best-known of them is possibly Leoba. She was an eighth-century Anglo-Saxon missionary and abbess of Tauberbischofsheim in Francia [note: Francia was an early medieval kingdom that, at its height, covered most of modern France, much of Germany and Italy, and even parts of what is now Spain and Corsica].

Earlier in her life, when Leoba was a nun at Wimborne, [in south-west England] she wrote to her kinsman, St. Boniface, asking for his protection and support. Boniface then invited her to join his mission to convert Francia to Christianity. The two of them worked closely together, even hoping to be buried together. That initial letter from Leoba is short, but it is significant. It contains the first poetry that we know to have been written by an English woman. She wrote, in Latin:

The omnipotent Ruler who alone created everything,

From ‘A letter from Lioba/Leobgytha/Leoba, abbess of Tauberbischofsheim (c.732)’

He who shines in splendor forever in His Father’s kingdom,

The perpetual fire by which the glory of Christ reigns,

The perpetual fire by which the glory of Christ reigns,

May preserve you forever in perennial right.

These lines are often dismissed as “derivative” of the poetry of bishop and scholar Aldhelm (c. CE 639–709). But I disagree. They actually show—quite clearly—Leoba’s rhetorical skill.

In the letter, Leoba also mentions the education that she has already received, and the poem illustrates her learning. In the letter, she also conveys her intellectual frustration and her desire to progress further. Leoba was ambitious. She felt the limitations of her position as a nun in England and recognized that with the benefit of Boniface’s patronage there would be greater opportunities for her in continental Europe. Boniface clearly saw her potential and set out to recruit her.

We don’t have any other letters from Leoba to Boniface. But we do have letters written to her after she had established herself in Francia. We also have a hagiography—a spiritual biography—of Leoba, written by the monk Rudolf of Fulda, which drew on the testimonies of the nuns in Leoba’s community. Together, these texts all contribute to our picture of her as an erudite and powerful woman.

M: I suspect many folks today aren’t used to hearing the terms “nun” and “ambitious” used in the same sentence! In addition to letters like Leoba’s, then, what kinds of evidence do we have for female authorship from this period?

D: There is one point I would like to stress from the outset. I think it is very limiting to talk just about female authorship. The romantic idea of great literary works produced by the creative imagination of a single author is really very unhelpful. And more, it is striking that, even today, anonymous early medieval literary works such as Beowulf are generally seen to be the product of an individual male imagination. What if some of the people telling the story of Beowulf—several, many, or even all of them—were actually women?

We know the names of some figures—men like Caedmon, who is often referred to as “the first English poet”, or the erudite Archbishop Wulfstan who penned the famous Sermon of the Wolf. These men have been given an almost iconic status that is simply not granted to their female counterparts, like Leoba, or Caedmon’s patron Hild of Whitby.

In the Middle Ages, literary production was highly collaborative. It depended on the contributions of patrons, scribes and religious communities. At the same time, literary reception was also communal. Books were read aloud publicly or within closed groups, and exchanged, shared and copied among networks of readers. That’s why my project is called “Women’s Literary Culture before the Conquest” rather than “Women Writers before the Conquest.”

I am, of course, interested in works written by women, some of which haven’t survived (but which we know about because they are mentioned elsewhere). But I’m also interested in works that may have been written by them, including some anonymous texts ascribed to men. I’m interested in works copied by female scribes, works produced for women (either as patrons and readers), works owned by women, as well as works that are indebted to women’s accounts—oral as well as written. That gives me a lot of material to work with!

M: It sounds like you have your work cut out for you! And I take your point that you have lots of different types of material to sift through. How do you deal with the fragmentary nature of the materials you’re working on?

D: Much of the material that I am working with is, as you suggest, fragmentary, in the sense that it is incomplete in some way and lacks an immediate context that enables us to make sense of it. This is true even of Leoba’s letter to Boniface. We have her letter, but not Boniface’s reply. The letters to Leoba that have survived—including two from Boniface—are from a much later date. I think the fragmentary nature of the evidence of early women’s literary culture has contributed greatly to it being overlooked.

Anonymous texts provide some of the greatest challenges. Today, at least, knowledge about the authorship of a text is usually seen to offer some sort of key to interpreting it. So a text that is anonymous might be considered, in one way, fragmentary. This means that its meaning seems less fixed somehow. These texts read a bit like riddles—and indeed, riddles were a popular medieval literary form. Megan, I know you’ve written about this really engagingly in your blog, The Riddle Ages. I’d really recommend this blog to anyone interested in riddles. It’s really fun.

M: Thank you!

D: Anyway, in marshalling evidence of female authorship of anonymous texts, I have to consider a whole range of issues. I have to look at everything from the contextual evidence about the production of the text, to stylistic evidence, to evidence that emerges from close textual analysis.

M: Speaking of multiple interpretations—what about intersectionality? Does your research shed light on sexuality, class, race, etc. alongside gender?

D: Intersectionality is really important here. The women I am researching are predominately royal or aristocratic. In other words, they are powerful and privileged white women who exercise enormous influence within their communities. As Paul B. Sturtevant has pointed out, medieval aristocrats often felt a greater affinity with aristocrats in other countries than with common people from their own. The societies in which they lived were marked by huge inequalities, where it was the norm for the wealthy to keep slaves. And of course, in setting out to convert the “heathens” of Francia to Christianity, the missionaries were engaged in what can be seen as an early form of colonialism.

We do get some insights into how these Anglo-Saxon women regarded people from beyond Europe. Another late eighth-century German missionary, Hugeburc of Heidenheim, wrote hagiographies of the brothers St Willibald and St Wynnebald.

Yes, Hugeburc [roughly pronounced HOO-ye-Burx, with the last “x” sounding like the “ch” in “loch”] is a woman’s name!

Hugeburc is the earliest named English woman writer of a full-length literary narrative—at least, whose name has survived. Hugeburc’s Hodoeporicon [or Voyage Narrative] of St Willibald offers an account of the saint’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In it, she describes Willibald’s encounters with Saracens [an out-of-date term medieval writers sometimes used to refer to Arabs and Muslims], including the Umayyad Caliph Yazid bin Abd al-Malik (also known as Yazid II). However, the references to women in these traveller’s tales are usually to long-dead female saints. Any real living and breathing women remain little more than shadowy figures in the background.

Thinking about sexuality, many of the women I am researching were, or had been, married. Some scholars even argue that Hild of Whitby was a widow before she became an abbess. But this doesn’t necessarily tell us much about their sexuality—marriages were often used to forge political allegiances.

Other women enjoyed close spiritual relationships with men, like Leoba did with Boniface. The evidence of friendships between women is often much more sparse. However in Nicola Griffith’s 2013 historical novel Hild, Griffith portrays her protagonist as having close partnerships with women, including a same-sex sexual relationship. While Hild is fiction, the reality is that we simply don’t know much about who was having sex with whom if procreation wasn’t involved.

In my recent article “A Fragmentary Archive: Migratory Feelings in Early Anglo-Saxon Women’s Letters,” I argue that there is something rather queer about some early women’s writing, in terms of the desires and emotions expressed, the temporalities experienced and the kinships forged.

M: Diane, we’ve talked quite a bit about the blurring of boundaries now, but not about the broader concept of gender itself. How is gender identity conceived of during this period?

D: Your choice of the word “conceived” is telling! Ideas of origins and inheritance, creation and reproduction, and matrilineage (tracing descent through the maternal line) are prevalent throughout the texts that I am examining. Gender identity, if such a phrase can be used, was less fixed—at least in an abstract, intellectual, theological sense. For example, women might be described, or might describe themselves, as “spiritual athletes” or “Christian warriors.” Yet, in reality, the lives of most women were very constrained.

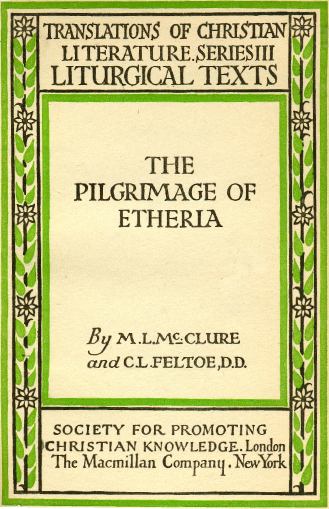

Hugeburc, in writing about Willibald’s travels to the Holy Land, mapped his pilgrimages as if she had taken them herself. But she was actually an armchair traveler, confined to her own monastery. This is in stark contrast with another writer, an Italian woman named Egeria, who in the late fourth century went on an extended pilgrimage to the Holy Land. She then wrote an account of this in a (now incomplete) epistle to a circle of other Christian women. Likewise, in the fifteenth century, the East Anglian visionary Margery Kempe went on a series of pilgrimages throughout England, continental Europe, and the Holy Land, which she later recounted in her book,which we know as The Book of Margery Kempe. So, some women were very well travelled indeed.

M: The complexity and multiplicity that you’ve been highlighting as we’ve talked brings me neatly to my final question: what modern assumptions about early medieval women and gender would you like to challenge?

D: I think it is so important to challenge modern assumptions about the early Middle Ages as the “Dark Ages … of the Female Imagination,” as Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, the famous editors of the Norton Anthology of Literatures by Women phrased it so elegantly and so erroneously.

The early Middle Ages in England was a period when women (albeit an elite minority of them) had access to education. Nuns had their own schools. Nuns had access to literary culture. Many could and did write letters, histories, and saints’ lives. Unfortunately, only traces of all this can now be seen, and you have to know what you are looking for. I am reminded of a remark made by the prominent feminist medievalist Jocelyn Wogan-Browne at the Barking Abbey conference in New York in 2009. She said that the great medieval educational institutions of men at Oxford and Cambridge are still standing and remain powerful and vital centers of intellectual life, while all that physically remains of the once mighty abbeys at Barking and Whitby are ruins.

That comment partly inspired the title of my essay “Literature in Pieces: Female Sanctity and the Relics of Early Women’s Writing.” Even if all that exists now are fragments, I would want people to remember that these scattered remains are evidence of a once vibrant and exciting women’s literary culture.

Diane Watt is a Leverhulme Major Research Fellow and Professor of Medieval English Literature at the University of Surrey. Her main research interests are gender and sexuality and women’s writing in the Middle Ages. Her publications include Secretaries of God (DS Brewer, 1997), Amoral Gower (University of Minnesota Press, 2003), and Medieval Women’s Writing (Polity, 2007). Her current research on early medieval women’s literary culture will be published by Bloomsbury Academic.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.