Dan Brown lied to you. I’m sorry.

I know it’s hard to accept. Who could have guessed that religious-themed thrillers might not reflect the cutthroat world of academia? I am a scholar of the papacy in the late Middle Ages. And since Dan Brown’s book Angels and Demons is still very much the reference point people have for my work, you might assume that I spend most of my time escaping hermetically sealed reading rooms and avoiding assassination. Sadly (fortunately?!), not so much.

But I’ve been to the Vatican Secret Archives.

I lived to tell the tale.

And I can tell you what it’s really like.

What makes the Vatican Secret Archives a “secret”?

The word ‘secret’ in the Vatican Secret Archives may be the reason for some of the rampant speculation about what goes on in there. But it makes the archive sound much sexier than it is.

The ‘secret’ part of the name comes from the Latin name, the Archivium Secretum Vaticanum. The word secretum has branched in English meaning. On one hand, it can mean “secret” or “hidden.” On the other, it can mean “personal” or “private” (in the sense of private property). This is what the name of the archive actually means—the personal archives of the pope. It is for this very reason that last year, Pope Francis changed its name to the Vatican Apostolic Archive to try and distance it from its reputation.

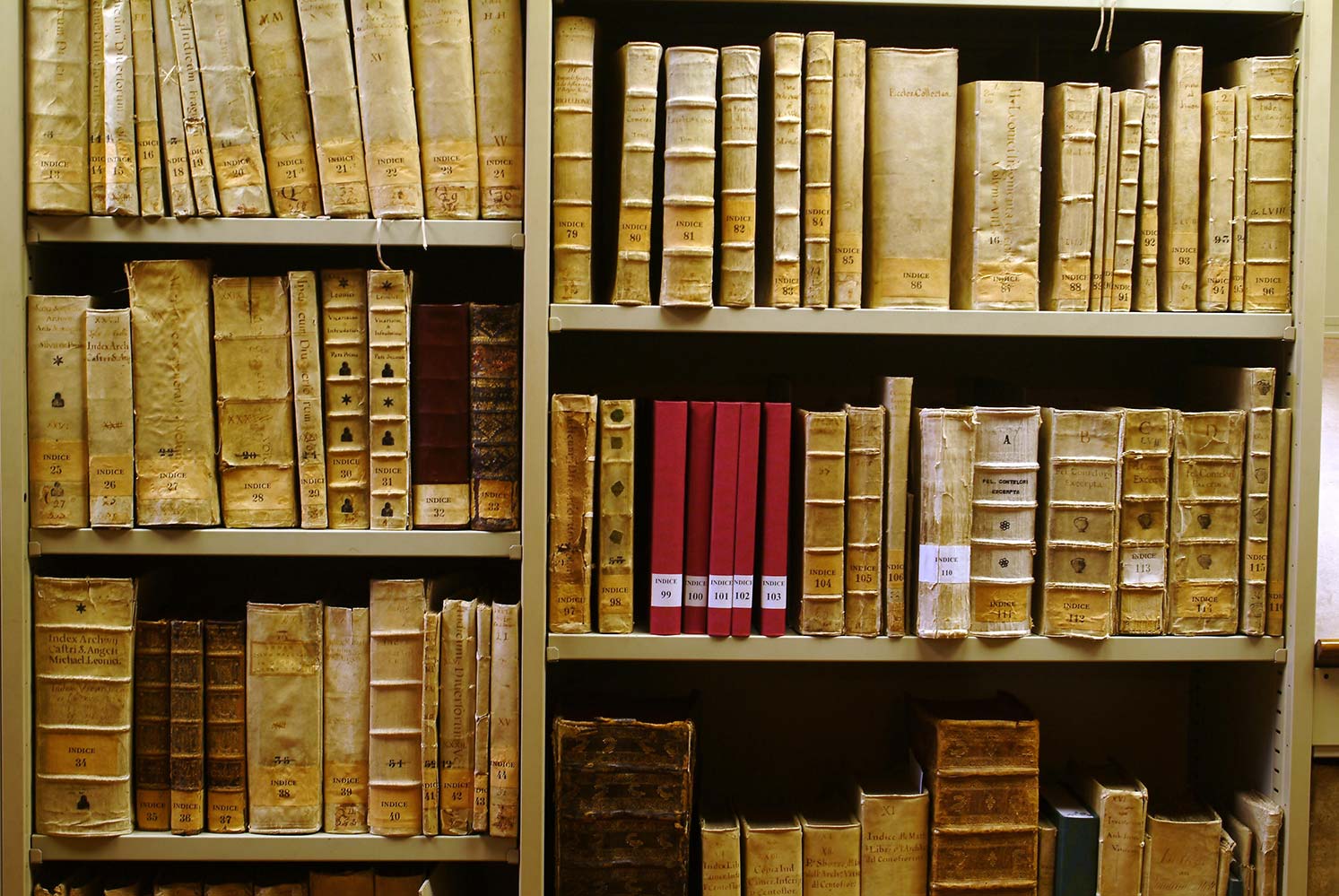

This already makes them a lot less exciting, I know, even if there are about 50 miles of shelf space in them. They are a treasure trove me as a medievalist, though, if not so much for conspiracy theorists.

The Vatican’s Medieval Treasure Trove

The Vatican archives have a lot of medieval material. There’s some material dating back to the 8th century, but it is very fragmented and rare. The medieval holdings mainly consist of books of letters and bureaucratic records, which start in the roughly 1205—though such items are quite limited for this century. By the start of the 14th century, though, we have loads of letters sent by the popes, petitions granted, and other such administrative records being saved. These give us some fascinating insights into a wide range of aspects of medieval life.

For example, the archives hold over 100,000 letters preserved in the main register series alone that date from the first half of the 14th century. These were produced by the main bureaucracy at the papal court and by the pope’s personal secretaries. And that 100k isn’t counting anything in the auxiliary registers, which were documents produced by the papacy’s specialised departments while documenting their work. These registers tell us quite a lot about life in the 14th century, both for the high European aristocrats in contact with the papacy and for lower-level petitioners.

Those at lower social echelons might navigate the papal bureaucracy to have some claim validated, such as having a land claim recognised, or getting their marriage to a slightly too closely related cousin legalised. High-level nobles may be discussing setting up crusades, peace negotiations with enemy states, or getting their marriage to a much too closely related cousin legalized. We can learn lots about what activity the papacy had taken an interest in, how Church administration worked, and what things medieval people sought official forgiveness for.

For example, through these we know that King Philip VI of France was well on his way to launching a crusade when the outbreak of the Hundred Years War in 1337 forced him to pull all his troops back to North France. We know about sordid crises between rival monks who fought to become the next abbot of their monastery. You find reams of land disputes between minor individuals otherwise completely lost to history. We even know more about international trade and travel—the papacy issued trade and pilgrimage licences that to visit to the Muslim world, and handed down punishments to people who did so behind the pope’s back.

Opening the Pope’s Mail

In this trove is a huge archive—nearly complete—of Papal letters. What a pope wrote to other world leaders can be quite revealing about their hopes and ambitions. Comparing the letters of different popes can help us understand what each thought was most important at the time.

The popes weren’t writing about secret deals to destroy the Templars. That deal was quite public, and all 60 meters of scroll detailing it are available to scholars. They’re not establishing global secret societies. The papal letters show us popes trying to maintain a semblance of European peace (when they’re not the ones disrupting it, of course) and preserve papal authority in the face of changing global politics.

They detail the popes’ efforts at negotiating with the Mongols and their missions to China. They even set up an archbishopric in Beijing at the end of the 13th century! The popes try to broker peace in the Hundred Years War. They were working to control the supply of war goods to the enemies of Western Christendom. They dwell on efforts to try and re-unify the Latin and Greek churches, which were separated first in 1054, and which were permanently ripped apart when the 4th Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204.

They detail excommunications for breaking the unity of Christendom, some for some pretty grand things, such as King Philip IV of France for having Pope Boniface VIII roughed up, or a Catalan private army for conquering Christian-held territories in the East. They also detail excommunications for smaller offenses, like transporting iron or slaves to war enemies.

They show in great detail how people reacted to theological arguments and heresies, both in Europe and in other Christian countries like Armenia (which was often suspected of being a bit heretical, but kept getting exonerated by the inquisitions). All this stuff is cool, but not “evidence-of-UFOs” cool.

But I was told there would be sexy hidden Vatican scandals and secrets!?!

What we don’t really learn much (or anything) about from these archives is hidden Christological conspiracies and supressed scandals. That’s not because these scandals were hidden, but because papal scandals were well-documented both inside and outside the papacy.

Much of the medieval material in these archives comes from a period called the “Avignon Papacy.” When most people think of the Pope, they think of Rome. But for nearly 70 years in the Middle Ages, the papacy was evicted.

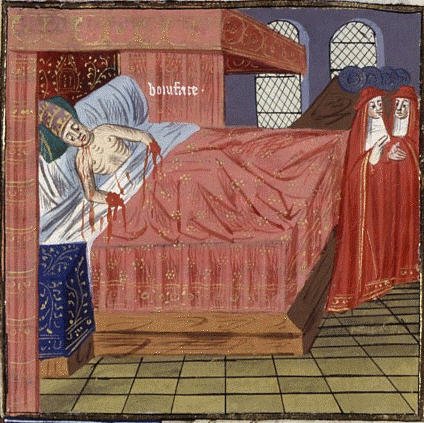

In the early 14th century, the papacy was forced to flee Rome; the papacy had had some very public disputes with the aristocrats of the city of Rome, and things were getting dangerous. In 1303, the 71-year old Pope Boniface VIII was beaten in his own home and died shortly afterward. From then on, the threat of physical violence against the popes was ever-present in Rome, so the papacy moved to Avignon, France. There, seven successive popes ruled as secular princes. Famed medieval poet Petrarch referred to the Avignon Papacy as the “Babylon of the West”. They were famous for misbehaving.

So, the Avignon papacy was no stranger to public controversy. They were vocally criticised by lots of people, even –in fact, mainly!— from within the Church itself.

For example, the second Avignon pope, Pope John XXII, raised several armies and had a very public war with the North Italian City States over several decades. This conflict devasted North Italy, and was—even in his own lifetime—considered extreme. John then caused a theological controversy with a bit of light heresy. Late in his life, he made proclamations about the end times—that dead people would only see God after Judgement Day, which was against Church doctrine then and now.

This might seem like a minor theological quibble, but a pope issuing a theology that was considered heresy was a big deal.

Fourth Avignon pope, Pope Clement VI, was famed for holding his court at Avignon as if he were royalty. He established a lavish and corrupt papal culture that was gleefully continued by subsequent popes in Avignon and by those who followed upon their return to Rome—such as the infamous Borgia popes (who have their own Game of Thrones-esque TV show). These popes called shady crusades for obviously personal gain, against Europeans or allies. Over and over again, they botched the political alliances directed at fighting the Turks and the Mamlūk Sultanate (an Egyptian empire that dominated the Near-East from the 13th to 16th centuries).

Another major public scandal of the late medieval papacy was between the Church and the Friars (a very powerful set of monks who had sworn themselves to poverty). They had a major spat over how much money the Church was splashing around on opulent living and secular power struggles and how much it was neglecting its moral duties. These controversies produced damning criticisms of the Papacy.

Returning to the Vatican Archives, it is difficult to imagine what scandals these records are supposed to hold that wasn’t public knowledge at the time. The same goes for most other time periods. For better or for worse, the Papacy is a very public, well-scrutinized institution both now and during the Middle Ages.

What the Vatican Secret Archives Looks Like

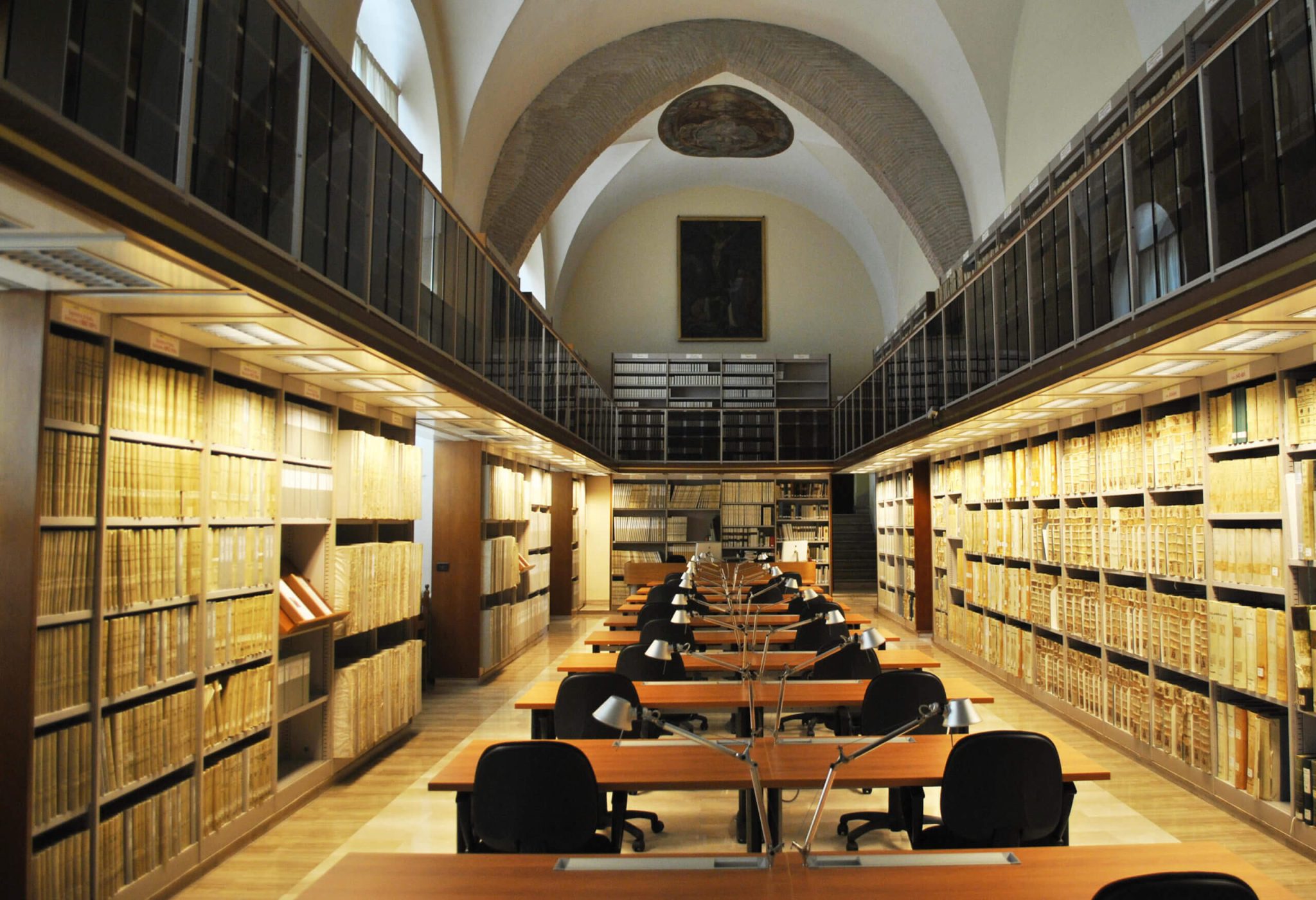

I’m sorry to disappoint again, but the archive is not in a secret underground bunker accessible only by torchlight and hidden doorways. The archive itself rests in what is, effectively, a series of climate-controlled warehouses. Visitors are not allowed to just go for a wander around them. The reasons for this are (almost certainly) more to do with mundane things like preserving the collection rather than preventing prying eyes from discovering nefarious secrets. Almost every major manuscript collection in the world operates like this, including every university archive I’ve ever visited.

This is simply because many of these books are centuries old—in some cases, older than a millennium. They are capital-F fragile. The ink can be easily rubbed off. The paper or parchment is brittle and at risk of breaking. Can you imagine the damage someone unsupervised could cause wandering around, randomly pulling out books? They could destroy centuries of material in minutes. So, as the archives begin to be digitised, the archivists prefer to lend out CDs with images of the oldest texts on them, even in the reading rooms, for this reason.

As a scholar, the part that you do get access to is the archive reading room. This is also much less exciting than you may have been led to believe. There is a suspicious lack of hermetically sealed climate-controlled glass boxes to be suffocated in. There aren’t even shadowy nooks to atmospherically add menace to your research sessions. It’s a quite pleasant set of rooms with lots of natural light and a series of rows of wooden desks. It’s… a library.

On a busy day, it will be about half full of scholars working in near silence. One room contains a set of slightly dated Apple Mac computers for viewing digital replications, but most of the space is set up for looking at the physical books. A café operates next to the reading room for those in need of a caffeine hit and a break, as entry to the archives is a lengthy process and the nearest coffee shop outside is back in Rome. All in all, it’s a quite an anti-climactic, if very nice, workspace.

How to Break Into the Vatican Secret Archives

Getting access to the archives is by no means easy, however. Here’s everything you need to know to get access.

You need a letter of recommendation from an established scholar at a reputable research institution. After that, a short interview conducted entirely in Italian is the price of entry. The letter is submitted with an application form well in advance, which specifies what area you’re interested in and when you would be using the archives. You then receive a letter inviting you to attend, which you take to the Porta di S. Anna, a side gate of the Vatican City, near the entrance to Saint Peter’s, on your appointed day.

After the colourful Swiss Guardsman on duty waves you through, you come to the security office. The first time you arrive, you must exchange your passport for a temporary security pass (on presentation of your invitation). Then, you’re allowed on, past the post office and the car park, to the archives themselves. There you sign into the archives, present all your documentation, and wait nervously for your interview. A certain amount of bad Italian, sign language, and written statements later, assuming everything has been approved, you’ll be presented with your real security clearance card. This allows you access to the part of the City with the Archives during opening hours, and crucially, allows you to get into the reading room.

Now here comes the hard part.

Once you get in, you simply hand in your card to the receptionist, sign in, then head into the locker room. To prevent damage to the manuscripts, no ink pens or photography equipment are allowed in the archive, including mobile phones. So, you have to leave everything behind except paper, pencils, and a laptop. You put everything else in your locker, carry your stuff through, find a free table, and make yourself comfortable.

To get material, you fill out a form requesting the specific volumes you want and give it to the counter staff in the reading room, then settle in for a wait. You can request up to five items a day, but the archives are only open in the morning. So, getting through more than that isn’t likely, anyway. You’re called up when your requests have been fetched, then you go to work!

Honestly, it’s not that exciting. Apart from the stringent initial security, the Vatican Archives work much the same as any other research archive. The procedure is almost identical in the British Library, or the Library of Congress. The archives aren’t open to the public, for sure, but the bar for entry isn’t prohibitively high. If you have a good reason for wanting to study the manuscripts in there, and you have a research degree to prove you can do it responsibly, it shouldn’t be impossible for you to study what you want.

Getting to the Bottom of It!

But none of this proves that there aren’t magic books, proof of UFO’s, or proof that Jesus didn’t exist being hidden in the archives, right?

But being allowed to wander around by yourself wouldn’t help you prove that either. That’s the issue with conspiracy theories. It’s hard to prove that something does not exist. And someone who wants to believe a conspiracy exists will find a way to believe in something that they want to be true. That says way more about their psychology than it does reality.

All I can say is that despite spending several years poring over the medieval contents of the archives, I’ve yet to encounter any oblique reference to the Illuminati. So far, I’ve not witnessed any efforts at murder in the reading room (though some of the scholars who make annoying noises…). I have yet to see a single armed monk wandering around the place.

What is there is a huge collection of materials that give a unique insight into the ordinary and extraordinary lives of people who lived hundreds of years ago, the problems they faced, and the way that people attempted to deal with them. They tell us about organisations and individuals, about fears and desires, ambition and failure. Ultimately, they tell us a fantastic amount about how humans lived. And maybe that will just have to be enough.