Part XXXIX in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Paul B. Sturtevant. You can find the rest of the special series here.

Sometimes it starts with a flag on the beach.

But first, a little context. This September, I took a vacation in Ocean City, Maryland. There was a lot to get away from. In addition to the general chaos and madness that has populated the news all year, three weeks prior had been the Charlottesville rally, where neo-Nazi medieval cosplayers murdered Heather Heyer and were subsequently called “very fine people”. A few weeks after Charlottesville, a medievalist at the University of Chicago crossed a major line by calling on her friend, Milo Yiannopoulos, to help target a medievalist of color who criticized her. Predictably, Milo’s army of followers began a major harassment campaign.

There have been a number of similar incidents too; medievalists have been grappling—sometimes with each other—with the racism that many of them see, both at the roots of this field, and also in the way the Middle Ages show up in so many racist incidents. When we launched the Race, Racism and the Middle Ages series here at The Public Medievalist, I certainly didn’t expect that events linking racism and medievalism would be splayed across the national news seemingly every week.

So if your medievalist colleague, teacher, friend, or spouse has been a bit more haggard than usual of late, this might explain it. It was a stressful summer.

Which might explain why, when I saw the flag on the beach, I nearly lost my damn mind.

Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Ocean City is a strange place. Most of its vacationing visitors come from the heavily diverse Washington DC, Baltimore, and Philadelphia areas. And Maryland fought for the Union in the Civil War—despite being a slave-holding state. But just by looking around, you can see how some locals have embraced a “Dixie” heritage that they never had. The tchotchke shops that line the beach have shelves upon shelves of items that bear the Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia (often incorrectly called the “Confederate Flag”).

As a stark reminder, it’s just down the road from Cambridge, Maryland, a heavily segregated city that saw violent clashes between its white and black residents during the civil rights movement. It is a place very much on the border.

On the boardwalk in Ocean City, Maryland, there is a shop that sells, primarily, flags and kites. And like most boardwalk shops, they had set out a display—this time on the beach—of their wares: a line of flags from Britain, Romania, Lithuania, Serbia, Ukraine.

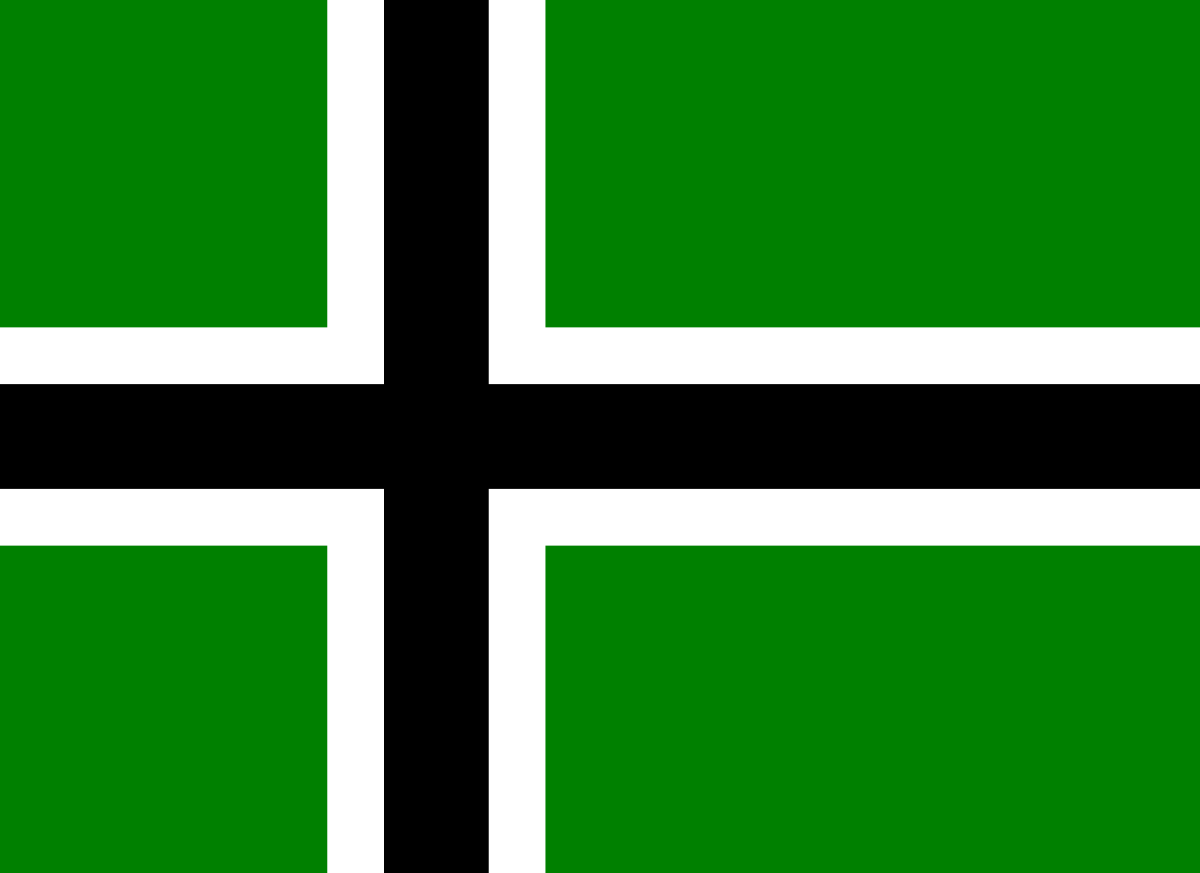

Then a flag at the end of the display caught my eye—a green field, with a Nordic cross in black. I flicked through my mental vexillological rolodex (built up from a youth wasted playing Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?), and couldn’t place it. It was clearly a Scandinavian flag, but it wasn’t a flag of any of the Scandinavian countries I knew.

With some Googling, I found the answer, and that set my medievalist spidey-sense tingling.

Vinland, Vinland, Vinland, the Country Where I Want to Be

That is the “Vinnland flag”.

For those unaware, “Vinland” is the name given to North America by the Vikings who visited it. The name is first reported in Adam of Bremen’s eleventh century text Descriptio insularum Aquilonis, where, in a conversation with King Sweyn II of Denmark, Adam relates:

He spoke of yet another island of the many found in that ocean. It is called Vinland because vines producing excellent wine grow wild there. [note: this etymology is probably incorrect] That unsown crops also abound on that island we have ascertained not from fabulous reports but from the trustworthy relation of the Danes.

But the Viking colony in North America was not to last. Scholars found a Viking village at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, dating to around CE 1000. But it was not occupied for very long.

And they certainly didn’t make a flag.

So where did this come from?

The Vinnland flag was designed in the 1990s by Peter Steele, bassist and singer for the popular goth metal band Type O Negative. This was apparently a fusion of the band’s colors (all of their album covers are black and green), and a representation of the singer’s interests in his Nordic heritage, environmentalism, and socialism.

This isn’t completely out of character for metal bands of that era. Several bands from this era fashioned new Viking mantles for themselves, because they considered the Vikings the ultimate bad-boys of medieval Europe. Simon Trafford and Aleks Pluskowski traced the origins and permutations of the “Viking metal” scene in their article “Antichrist Superstars: The Vikings in Hard Rock and Heavy Metal.” Several metal bands, especially (though not exclusively) ones originating in Scandinavia, appropriated Viking imagery and mythos through an hypermedieval, hypermasculine, misanthropically anti-Christian, anti-establishment lens.

So I’m sure you can see where this is going: this hypermasculine anti-establishment form of heritage often crossed the line into racist far-right nationalism. This closely echoes Nazi Germany’s own attempts to appropriate Viking symbols and mythologies, as Julian Richards explains:

In Germany under the Nazis a more sinister interpretation of Vikings developed […] When they came to power in 1933 they began a crusade against modern ‘decadent’ culture, systematically replacing it with their own version of Aryan culture, based on Vikings, Old Norse mythology, Wagner, and German peasant culture. The Vikings became part of the fair-haired, blue-eyed, clean-living ideal of the National Socialist Party.

But, as Trafford and Pluskowski explain, it’s important not to paint all metal bands with the brush of neo-Nazism:

an undercurrent of racism, nationalism and anti-Semitism continues to permeate many parts of the black metal scene. On the other hand there are a number of bands who are merely extremely interested in the Vikings, and Norse mythology in particular […] There are perhaps as many definitions of what constitutes Viking Metal as there are fans.

Type O Negative wasn’t an out-and-out Viking metal band like Enslaved or even Manowar. They only very occasionally used Viking imagery; the clearest connection to an imagined Viking past was in the Vinnland flag. Like the Vikings themselves, Type O Negative was open for interpretation by their fans, some of whom were (or are) white-nationalists. For example, ‘Vinnland’ has had a (deeply odd) website since 2007, the very end of the band’s career. It seems to be fan-created—though it is unclear exactly who wrote the site or why. It espouses a bizarre mythological origin story for the band:

For over 300 years the peoples of Vinnland have been suppressed by their corrupted rulers. Their history eradicated, their culture trampled under the boot of American capitalism and imperialism. Many were driven westward and put in “reserves”. Others were made to abandon their old practices and forcefully integrate into the society of the capitalist oppressor. Futhermore they were violently forced to convert to Christianity, abandoning their believes in the Æsirs, and forced to believe a monotheistic lie.

But the Vinnland blood strain, pale skinned, black haired people are spread throughout the lands of America.

They live unnoticed among us and wait for the day they can reclaim the country which is legally theirs and which they love so much. Under the leadership of the fearless Peter Steele the United Vinnland Peoples Front (disguised as the band Type O Negative) spreads its message of paganism, love for nature and socialist political ideals to the indigenous population of Vinnland.

This has all the hallmarks of the worst excesses of the Viking metal scene: a mythos created around anti-establishment and anti-Christian narratives that quickly pivots into a racist mythology about superior blood lines. But further resisting simple readings, it’s possible that this was all a half-baked joke. As a profile of Peter Steele, the band’s frontman, in The Atlantic upon his death in 2010 states:

Steele took nothing and everything seriously. Upon moving record labels in 2005, the band released a tombstone image on its Web site faking Steele’s death. Indeed, no one was ever sure if Steele was joking when he created a false, quasi-Nordic nation Republic of Vinnland, including a flag. Though he grew up in Bensonhurst and was close with Jewish bandmate Josh Silver, Steele’s half-baked deconstruction of American social welfare policy “Der Untermensch,” may not have been the best choice of language and topic for a song. The “Nazi sympathizer” tag followed Steele throughout his life.

A Riddle, Wrapped in a Mystery, Inside an Enigma

It’s easy to see then how Type O Negative might appeal to neo-Nazis who, rightly or wrongly, saw their ideology reflected in the band’s music and mythos. And so, those neo-Nazis appropriated their symbol; when you Google “Vinland Flag”, the first result is an entry from the Anti-Defamation League’s Hate Symbols Database. As the ADL writes:

In the early 2000s, white supremacists (most notably, the Vinlanders Social Club, a racist skinhead gang) began to appropriate the flag as a white supremacist symbol. Common variants involve adding one or more other hate symbols to the flag.

Despite its increasingly common use by white supremacists, many non-racists (including fans of Steele and Type O Negative) also use or display this symbol, so it should always be judged carefully in its context.

Having discovered all of this, while staring at the odd flag waving in the summer breeze, my eye started to twitch.

I was suddenly confronted with two equally likely possibilities:

- on the one hand, the Vinnland flag waving at me could be yet-another appropriation of the medieval (or in this case, a medievalism) by white-supremacists in order to push their hateful agenda;

- on the other hand stood the possibility that someone in the shop was not a neo-Nazi at all but simply a fan of Type O Negative, or mistook the flag for one of a real country.

Was it a racist dog whistle? Or was it simply a band flag?

Following the ADL’s advice of judging carefully in its context didn’t help either; the shop was an innocent-seeming place, full of flags and toys and kites and no obvious signs of white supremacy. On the other hand, one of the flags they flew outside was the “Thin Blue Line” flag. This flag was originally created to honor the sacrifices of police officers, but, you guessed it, the flag has subsequently been appropriated by those advocating that “Blue Lives Matter” in opposition of the Black Lives Matter movement.

So was this flag a white supremacist appropriation of the Middle Ages? I don’t know. And without more information about the person who chose and raised that flag, I can’t know.

That’s why I call it a Schrödinger’s Medievalism.

Quantum Medievalism

In the famous “Schrödinger’s cat” thought experiment, Erwin Schrödinger said (entirely theoretically) that because of quantum mechanics, if you put a cat in sealed box with a flask of poison and a radioactive trigger, you cannot tell what state the cat is in—whether it is alive or dead—without opening the box. So, without more information, the cat can, weirdly, be considered both alive and dead at the same time.

So, that Vinnland flag was a “Schrödinger’s medievalism.”

To my mind, a Schrödinger’s medievalism is a piece of medieval culture found in the wild that you know has been appropriated as a symbol by right-wing nationalists or racists. But, that piece of culture also has a broader, potentially benign, meaning. You can’t tell which is it until you get more information—and sometimes doing so is impossible. So, sometimes you are left in the uncomfortable position of having to treat it as both benign and hostile at the same time.

Another example of a Schrödinger’s medievalism involves something that Sierra Lomuto discussed in an excellent essay at In the Middle. Lomuto relates how she encountered a tattoo artist—who specializes at translating Celtic imagery from medieval manuscripts into body art—at a conference. There is nothing inherently racist about getting a Book of Kells inspired tattoo. But, as Lomuto explains, things took a turn in the Q&A session:

When asked about her clients’ motivations by an audience member, the artist explained that her clients are white people looking for a heritage to celebrate during a time when “being white is bad.”

She further explains:

It is one thing for an Irish person to celebrate their ethnic heritage with a Celtic tattoo and quite another for a white person to use Celtic iconography to symbolize their racial whiteness despite their actual heritage. Race and ethnicity are not interchangeable categories of identity. To celebrate one’s Irish, German, or Italian ethnicity is akin to celebrating one’s Ethiopian, Chilean, or Thai ethnicity. There is no equation to be made between whiteness and ethnic heritage. Whiteness is a racial category of privileged dominance; it is a power structure upheld by the oppression and marginalization of non-whiteness.

And Lomuto was not speaking from theory here; the conference presenter’s name was fêted on the neo-Nazi website Stormfront as someone who could provide racist body art that could fly under the radar:

the OP [Original Poster] asks for tattoo ideas and our conference speaker’s name is suggested along with the advice that Celtic crosses work better for tattoos because they are not as obvious as a swastika. The OP expresses concern about being ostracized for his beliefs, fully aware of the negative perception of white nationalists, and his respondents offer him ways in which he might be more covert. A Celtic tattoo is one such suggestion.

The Celtic tattoo is thus also a Schrödinger’s medievalism; if you spot someone wearing one, it is not immediately obvious whether the person sporting it is doing so for toxic reasons. And naturally, not knowing this can be anxiety-inducing.

Another example: I attended the Maryland Renaissance Festival this year, and in the crowd I noted a small group of four young people. They were all cosplaying, and all wearing replica amulets of Thor’s hammer. Thor’s hammer amulets are complicated; the ADL Hate Symbols Database has an entry for it.

For some white-nationalists, Thor is an icon of white Aryan warrior masculinity. But Marvel’s Thor comic books and films have been reimagining the Norse mythological tradition in a way that is more inclusive than ever. And notably, three of the four cosplayers I saw were people of color. For them, it seemed that Viking religion was simply cool, and the amulets were part of a fun costume.

White supremacists try to appropriate these sort of symbols precisely for this reason: it’s easy for them to hide in plain sight, allowing them to slip under our radar. And even more insidiously, when it comes to light that these are sometimes used as symbols of hate, it can make white supremacists’ numbers seem greater than they really are. To extend the metaphor, it floods our radar with false positives, causing us to see white supremacy everywhere, even in places where it is not.

Having written about the white supremacist attempts to appropriate the Middle Ages this year, I now see Schrödinger’s medievalisms all the time. And in the light of the very real white supremacy splayed across our politics and our news every day, it’s very difficult not to get freaked out.

On What Hills Do We Die?

This leads us to the final question: what do we do about it? This is a critical question for anyone who loves the Middle Ages in a time of resurgent blatant racism. Broadly speaking, there seem to be two options: we can cede the territory, labeling these symbols entirely problematic and banning them outright. Or we can fight for them.

The answer is not quite as simple as it might seem—there are benefits to the former. If we cede the territory, that makes our radar clearer; if we make it clear that the Vinland flag should today be always considered a racist symbol, then we know what it means when someone flies it. It makes the world a little less ambiguous, a little less scary.

But that has drawbacks, too, because it is ceding the medieval history we love and study to those who would twist it for their aims. Of course, some symbols have definitely been compromised to such a degree that they are likely unrecoverable; unless you follow Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism, the swastika is not for you.

But there is value in fighting for our more-ambiguous historical symbols. It shows that, as people who love the Middle Ages, we are not willing to leave it to be twisted by those who would use it to promote a hateful agenda. It shows that the Middle Ages itself is not what those who abuse it say it is; it is broader, more complex, and more inclusive than they would ever imagine.

There is absolutely no reason that those cosplayers shouldn’t have worn Thor’s hammer to the renaissance fair. Though it is used as a racist symbol by some, it doesn’t belong to white supremacists. And even a supposed “historical accuracy” argument doesn’t hold water; we have found evidence that suggests that a few people of color may have worn them during the Viking Age!

Yes, the Nazis used (and neo-Nazis still use) Viking symbols. But let us not forget, as Lars Lönnroth reminds us in his chapter of The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, that these also offered strength to those fighting the Nazis:

As a matter of fact, Viking symbols were also used by the Resistance movement in its underground war against the German occupation. One legendary Resistance group in southern Denmark, for example, was named Holger Danske after a famous Old Norse saga hero. Its members mainly consisted of farmer who had grown up in the Grundtvigian folk high school tradition and therefore found it quite natural to be inspired by Norse mythology in their struggle against the German enemy.

This is, in essence, what we have been trying to do with the The Public Medievalist’s Race, Racism and the Middle Ages series: fighting for the idea that the Middle Ages is not territory that we are willing to cede, and showing that the Middle Ages are also full of stories that can offer us strength and hope today. So if white supremacists want it, they are going to have to go through us.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.

Great article, Paul. Reminds me of the shop(pe) selling Templar costumes at King Richard’s Faire in MA, which was a bit of a shock until I processed it. Plus, Manowar!

I have a Mjolnir necklace I’ve been really hesitant about wearing ever since Charlottesville, especially since I work at an HBCU. I still do *because* I don’t want to let the racists have it, but I wear it a lot less often than I used to. 🙁

I totally understand the hesitancy. I think one approach might be to always pair Mjolnir with another symbol that unambiguously shows your values. Recontextualizing the symbol may be a key to this fight.