Sadly, life is too short to see everything you want to see.

For those people – historians and non-historians alike—interested in the medieval world, a sort of “bucket list” quickly develops of all the “medieval” places you want to go. For me, that bucket list includes those places that I simply must see, either because of an event that happened there, a truly singular object held there, or because of an extraordinary building in that place.

Off the top of my head, my medieval bucket list includes (in no particular order):

- Istanbul, and especially the Hagia Sophia

- Neuschwanstein Castle, in Bavaria (yes, I know it’s not medieval, but oh the medievalism!)

- Iceland (the whole country)

- L’Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada (the only confirmed medieval settlement in the Americas)

- Jerusalem (the literal centre of the European medieval world)

The list goes on. But I imagine for most people, no matter the length of their list, it probably would never include the city of Leeds, in the United Kingdom. Though European medievalists know Leeds for the International Medieval Congress held there yearly, for others it’s understandable that Leeds passes without mention. During the medieval period Leeds was a rural backwater by contrast with its beautiful (and bucket-list worthy) neighbours York and Durham; it has no castle of its own, no city walls, no cathedral.

However, in Leeds there is one destination that should give those people interested in the medieval world a reason to add it to the list: The Royal Armouries, the largest and, by my estimation, best-curated museum of arms and armour in the world.

In the early 1990s, the British government decided that it needed to rehouse the collection held by the Tower of London, which, while an impressive edifice (and itself worthy of the list) is not a really suitable place to house and display their immense treasure trove of arms and armour. Thus, it was decided that a huge, purpose-built museum would be created in Leeds; the new Royal Armouries building was opened to the public in 1996.

The basic statistics of the museum are impressive enough. Its collection includes over 70,000 pieces of artillery, armour, and weaponry. Their library is also the foremost collection of original fencing manuals and military drill books. And while my focus here is on the medieval militaria (which comprises a whole floor of the building), they also have an impressive (if smaller) collection from Japan, India, and the Middle East, as well as a gallery of weapons for hunting and for self-defence.

If you are the sort of person who goes to a museum specifically to see extraordinary, famous or unique objects, it has a number of those as well. It houses Henry VIII’s foot combat armour, arguably the most technologically-advanced suit of plate armour ever made. They hold the Lyle basinet, the finest example of a fourteenth-century helmet in the world.* They have the only full set of Indian elephant-armour in existence. And for those interested in film depictions of the Middle Ages, they have a growing collection of prop weapons and armour due to a close collaboration with Weta Workshop (the craftspeople behind The Lord of the Rings and Narnia franchises).

But as a public historian and a museum evaluator, to me this is all icing on the cake.

Museums are not created equal, of course. Some, like the Royal Armouries, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution or the Louvre have an embarrassment of riches. They have entire collections—often larger than what is on display—of artefacts in storage either because they are too fragile to display constantly, too similar to something already on display, or simply because they do not have the space for it. And they often have an embarrassment of literal riches by contrast with smaller museums; though there is no such thing, in my experience, as a fully-funded museum, the support given by governments and wealthy benefactors to these major, national museums allows them to do far more than their smaller counterparts.

So, when evaluating a museum, I always try to look beyond what they have and see, instead, what they do with what they have. I will talk more about this in a subsequent post, but suffice it to say that a museum can have row upon row of unique and precious objects. But if, like so many museums, they are only affixed with little labels giving a name and a date, that is not good enough anymore. This becomes little more than a glorified curiosity cabinet of a nineteenth-century antiquarian. It may have impressive objects, but the objects have no meaning—I feel no personal connection to the people who made and used them, I don’t see the ideas behind why they are important enough to warrant inclusion in the collection. In short, in a museum, interpretation is king.

It is along these lines that I feel The Royal Armouries does a—perhaps surprisingly—good job. It is not a nineteenth-century museum, in two very important respects.

First, it is not a nineteenth-century museum in that it works hard to present interpretations of its objects that make them meaningful for people in the present, and allow them to better understand the objects on display. In one example, in the tournament gallery there is a wall-illustration with two titles: “Made to Measure” and “Dress to Impress”. This wall-exhibit is intended to draw the connection between medieval jousting knights and contemporary football stars in Britain, particularly in the way that each of them is judged based upon style as much as substance, and that each dressed accordingly. A quote by Giorgio Armani makes this comparison quite clear: “Football players are the new style leaders… I have the opportunity to dress heroes”. In the specific niches, there are examples of tournament armour pieces illustrating this overall idea—and ultimately reinforcing the overall idea which bridges the gap between medieval and modern. This, in a humanistic sense, allows us to see some of the ways in which we are not so unlike our medieval forebears after all.

Not all of the interpretations are as successful as this one. And disappointingly, their recent budget struggles are obvious. In the past few years, many of their first-person interpretations have been reduced or cancelled altogether. And on my last visit, about a third of the interactive exhibits did not work properly. But I give the Armouries significant credit for striving to interpret their collections thoughtfully.

And it is this thoughtfulness which raises the other significant way in which the Royal Armouries is not a nineteenth-century museum. As a national museum of arms and armour, it would be very easy for the Royal Armouries to slip into nineteenth-century modes of thinking about the topic of war. Thankfully, they have shown themselves to be resistant to a nationalistic agenda which would recount the glories of their nation’s fighting past. I only found one gallery which indulged in this kind of thinking; a room with a diorama of the Battle of Waterloo, dominated by an array of weapons spread decoratively on the wall in a manner not out of place in a Victorian stately home.

But aside from this deviation, there is a consistent—if nuanced—message about warfare and combat that pervades the museum. It seems to say that war has been a constant throughout human history and should be respected as such, but in all cases it is lamentable. As such it falls somewhere between a museum of national history (like the Smithsonian National Museum of American History) and a museum of a tragedy (like the Holocaust Museum in Washington, or the newly-opened 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York).

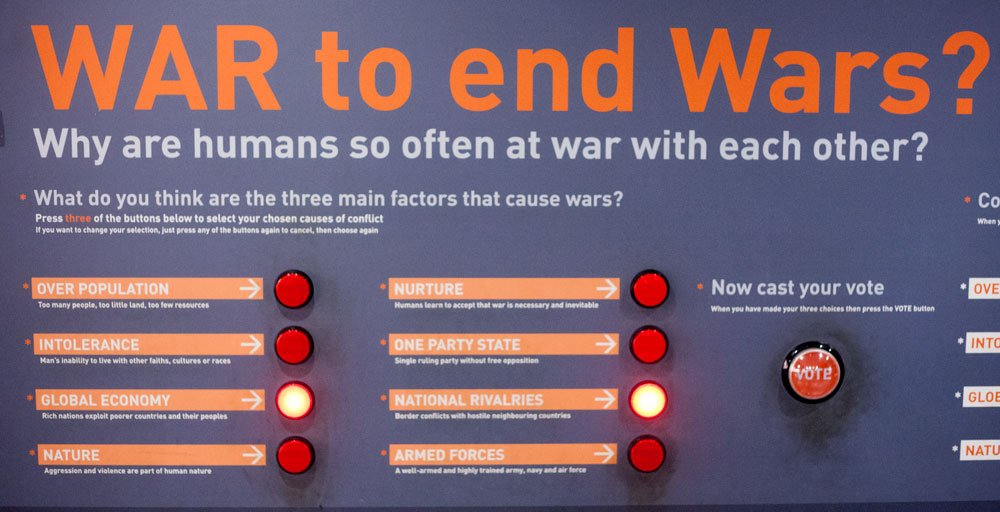

For example, upon walking into the Hall of War, the visitor is first confronted by two interactives which ask “Why are humans so often at war with each other?”, and “Why do human beings find it difficult to live in peace?”. Visitors are presented with eight possibilities, and asked to vote for three. But unlike many interactives, to this there is no “right” answer, only a question of opinions. Importantly, though it displays how many visitors voted for each response, it does not think to provide a definitive answer, which goes some way towards framing what the visitors will be seeing in the rest of the Hall of Steel. This is further reinforced in their Peace gallery, which highlights the contributions of organisations and individuals that have worked to end warfare and violence in the world. War is not something to be celebrated, but struggled against. And war is not a question specific or exclusive to one nation, but endemic for all humanity. As such, the Amouries positions itself well not as a national museum but an international one.

This is why I recommend the Royal Armouries highly as a destination for those people interested in the medieval past. It is not for the size of the collection or the unique extraordinary objects, but for the thoughtfulness of the curation. The fact that they have taken it upon themselves as their mission to forge new connections between the medieval past and the present day, as well as the nuanced way that they address the difficult questions surrounding remembering the military past puts them head and shoulders above many other museums on this topic. So, while scratching the medieval glories of York and Durham off your bucket list, don’t forget to take a side trip to a medieval backwater with an extraordinary museum.

So what’s on your medieval bucket list?

Note: For full disclosure, I know some of the curators of the Royal Armouries, however all of the opinions here are mine.

* Correction: The article originally stated that Henry VIII’s armour was medieval, whereas it is only debatably so, having been crafted during the 16th and early 17th centuries. Also, this article originally stated that the Lyle basinet is a helm; it is actually a helmet. Thanks to Dr. Nick Dupras for the corrections.

I’ve been to Neuschwanstein – it’s absolutely lovely. And you’re right – the sheer amount of medievalism is absolutely staggering … As for my medieval bucket list, it would probably be the IMC (seriously) or else Kalamazoo. The Bayeux Tapestry was on there until I actually saw it a couple of years ago, and it was every bit as impressive as it’s made out to be.

It is less well-known by the English-speaking world but the musée de l’Armée, in Paris has a larger collection (about 500 000 objects from prehistory till today estimated…) but not all of them are on display of course (for the fanatics they have boxes and boxes of sword pommels in store for example…). With a large collection of medieval stuff. But the display is more classic… they don’t do public history^^ I personnaly also prefer the Royal Armouries’ display, it is far more educational and accessible.

I also advise you the Kunsthistorisches museum in Vienna and the Real Armeria in Madrid, also two of the largest (and the best) collections of arms and armour in the world, even if these two house mostly high quality stuff (royal and imperial weapons = high concentration of masterpieces), when in Paris or in Leed beside royal objects you found also a lot of more “everyday” arms and armour…

I wasn’t wild about the Real Armeria in Madrid, I must confess. One of the main issues there was that they strictly forbade the taking of any photographs; I am well aware of the damage that flash photos can do, but without a flash the only reason to disallow it are because you want to sell the images. It’s not a great philosophy for what is a publically-funded institution, and makes it very difficult to study the pieces. As you can see from my review, the Royal Armouries have no such restrictions!