Review: “Waste Not: The Art of Medieval Recycling” at The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, through September 18, 2016. Free.

“There’s no right spot in the galleries for him,” says Dr. Lynley Herbert, Assistant Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Walters Collection in Baltimore. We’re staring at a larger-than-life marble head of Hercules in the center of the room, his fierce expression frozen in time. This Hercules is unlike other Greco-Roman statues. The issue is the holes—a series of holes— big enough to almost fit a pinky into— that have been drilled into the statue: one in each eye, and a line of them punctuating the curls of his beard and the tips of his mane.

This Hercules was originally carved in second-century Florence. But as time passed and the world changed around it, Florence no longer had need of larger-than-life Greek supermen. So in the 14th century, 1100 years after its creation, it was given a new life. The head was found, given the line of holes it bears today, and repurposed into the head of a saint. The holes were probably carved to make the details “pop” from a greater distance.

But therein lies the problem for Dr. Herbert—is this head Roman, or medieval?

It is clearly both. But art museums, like so many academic institutions, have difficulty with things that do not fall into clear categories. Herbert, in her exhibition “Waste Not: The Art of Medieval Recycling” currently mounted at the Walters, wants to challenge these calcified ideas.

Ostensibly, the exhibition’s theme is recycling. “People think of recycling as a very modern thing,” says Herbert, but “Recycling has been going on for thousands of years.” And Herbert has displayed a series of fascinating objects that illustrate this point in a variety of ways.

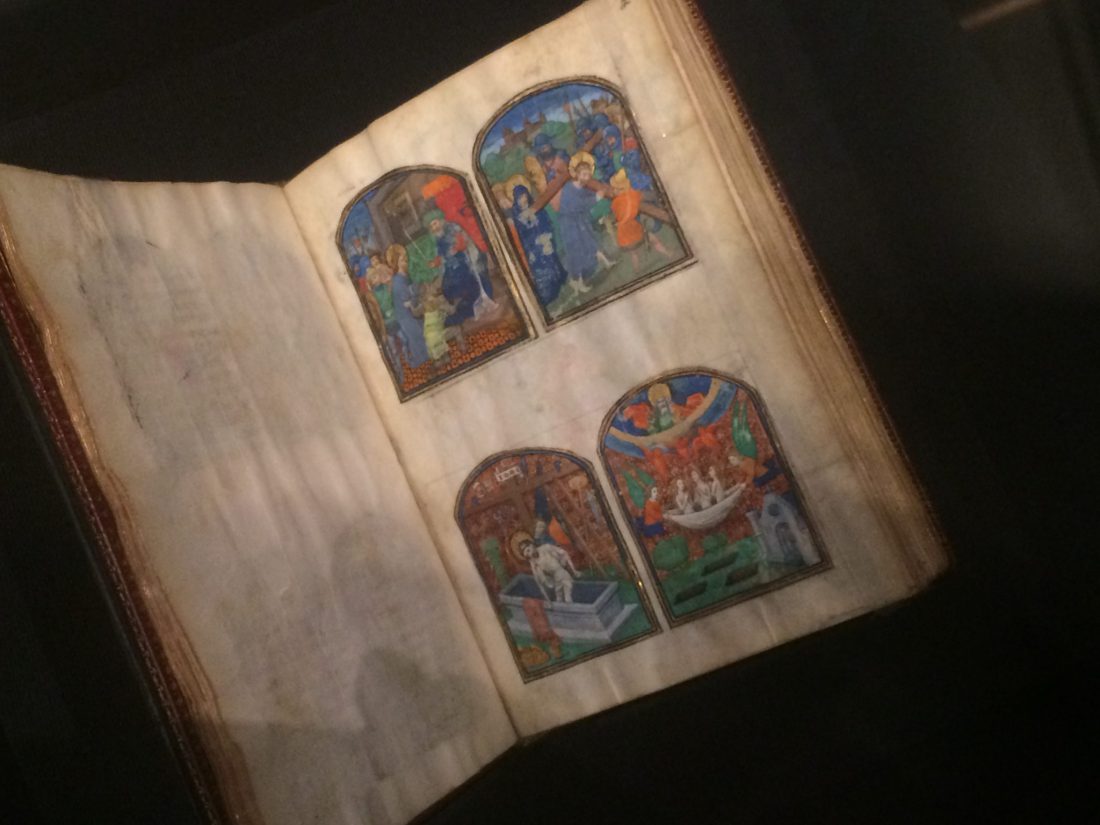

There are those objects that were recycled—like the head of Hercules—either as a cost-saving measure or because local craftsmen of similar skill were hard to find. But there are other types of recycling at play too. An early-modern printed copy of Aesop’s fables—despite being made on a very early printing press, not an especially rare book, all things considered—has a unique cover: a scrap of Talmud, handwritten in Aramaic from the 12th century. A Byzantine ring set with a blue cameo of the goat-legged god Pan—clearly a relic from the ancient world—but given a new context with an inscription from Psalm 26: “Lord, my Light and my Savior, whom shall I fear?” A small prayer book from the 17th century sits open, revealing tiny images which have been cut out of a 15th century book of hours and carefully pasted in this “new” work. A 12th century cross is set with beautiful blue enamel, now found to have been made from melted roman glass.

The essence of the exhibit is about the recycling of materials and ideas – both medieval people recycling from the past, and post-medieval people recycling from the Middle Ages. Unlike common perceptions of history, where each era marks a clear break from the ones before and ones after, this exhibition shows how reliant every era is on its past. Both the materials and the ideas of the past are the crucial building blocks for each new age.

In fact, there is only one fundamental difference between recycling of this type and our current blue-bin recycling. Each of the examples in the exhibition are a result of recycling due to lack and scarcity. The Talmud was used to wrap Aesop because, as Herbert noted “You’re not going to be able to run down to Office Depot and get more parchment.” The Roman glass was reused in medieval enamel because they no longer had a ready supply of crucial natron flux.

Western society is no longer beholden to that lack of materials. We can go to Office Depot for paper. If we want images from a fifteenth century book, we can print them from the internet. We are awash in glass. Living in the age of mechanical reproduction (and now, 3D printing), has led to an incredible bounty of art and of images. And with that bounty has come disposability.

And perhaps that is the only fundamental difference between the recycling seen here and contemporary blue-bin recycling. We recycle bottles not because we wish to save glass, but because we wish to save energy. And we wish to save energy because we wish to save ourselves. We recycle because the very culture of disposability that has freed us from needing to recycle has begun to threaten our very existence on earth. And so, we recycle. As the exhibition notes,

“recycling, upcycling, and adaptive reuse have become necessary responses to the growing awareness of our planet’s limited resources and to the environmental damage caused by our everyday activities.”

And that may be what is most interesting about this exhibition—that it so deftly reveals the links between our way of being and that of the past, while remaining respectful of the distances between the past and present.

Perhaps the only criticism of the exhibition is that it relies so heavily upon the past in terms of its design, layout, and engagement. The exhibition is in a small, unassuming space in the Walters, and does not announce itself or its intent very loudly. The way in which the objects and ideas are presented are entirely traditional—objects accompanied by well-crafted text panels on walls and podia. The text itself is refreshingly casual in points, relating the ideas behind the objects to modern ideas like “name-dropping.” But the panels are short, and left me wanting to know more (why was this page of Talmud chosen? What does the text on it say? What saint was Hercules supposed to be?, etc.).

And as is common in many art museums, the experience of visiting the exhibition was infinitely more enjoyable and enlightening when accompanied by the curator of the exhibition—its taupe-on-taupe, small-text design does little to announce this exhibition as something as special as it is. It is perhaps ironic that the only significant flaw of this exhibition is the fact that that the way it presents its ideas have been largely reused from the past.

But in spite of this, it is an excellent exhibition that seeks to break the mould in an exciting way. It shows that the walls within the gallery and within our understanding of the past deserve to be questioned, complicated, and even removed. It may not look like much, but this is an excellent exhibition. As such, I highly recommend that you take the trip to the Walters before it closes on September 18th.

Full Disclosure: I was contacted by the Walters and asked to review this exhibition, and interviewed the curator while touring the exhibition. I was not offered nor given any compensation for this review.

Comments are closed.