This is Part XV of The Public Medievalist’s continuing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Richard Utz.

You can find the rest of our special series here.

This article is an extension of a chapter in his recent book, Medievalism: A Manifesto, currently available from Amazon here and directly from the publisher here. A Public Medievalist review of the book is forthcoming.

Atlanta’s Rhodes Hall, built in 1904, recoups some of the costs of its upkeep by offering itself as a venue for banquets, celebrations, and feasts. In fact, since 2012, it has been a winner of a Bride’s Choice Awards™ for best wedding ceremony and reception venue. So popular is the site that renters are willing to fork over $2,000 for a four hour event on Monday through Thursday, and $3,500 for one on a Saturday.

The owners can do this, in no small part, by capitalizing on the fantasy of being married in a castle.

But do couples really know what kind of history they are entering when they get married at Rhodes Hall? While the hall may overtly project an image of fairy-tale medievalism, when you scratch the surface, you find something altogether darker and more complicated.

History of a Georgia Castle

The origins of the building also have to do with love, in this case, the love between Amos and Amanda Rhodes. After a trip to the Rhine castles in Germany, they wanted to have their very own private castle built in one of the most ostentatious areas in early twentieth-century Atlanta.

Amos Rhodes, had fulfilled his American dream. He had risen from a position as regular laborer for the L. & N. Railroad to become one of the richest furniture entrepreneurs in the South. And he was eager to display his wealth in the quickly growing city. Amos and Amanda asked renowned architect Willis F. Denny II (1874-1905) to construct their new residence.

Denny had previously designed two churches in the Gothic Revival style: Atlanta’s First United Methodist and St. Mark’s United Methodist. He then built the Rhodes’ home in 1904 in a similar style, Victorian Romanesque Revival, which was normally restricted to large public structures (courthouses, churches, libraries, university buildings, department stores, and train stations) like San Francisco’s St. Mark’s Lutheran Church (1895), Chicago’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1887), and Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building (1898). The Rhodes family called their new mansion “Le Rève” (“The Dream”).

The granite for the mansion was quarried twenty-five miles east of Atlanta from Stone Mountain. This was the same Stone Mountain which would, in 1915, become the site for the founding of the second Ku Klux Klan, and for which, also in 1915, the Daughters of the Confederacy would commission a carving of the Confederate icons Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. This connection is more than simple geographical coincidence. The Rhodes family settled in their castle in a quickly growing modern Atlanta, a city which, in part because of its modernity and rapid growth, offered better living conditions and career opportunities for both white and black workers and businesses than any other city in the late nineteenth-century South.

A Changing Atlanta

Between 1890 and 1910, Atlanta’s total population rose from 80,000 to 150,000; the black population grew from about 9,000 people in 1880 to about 35,000 by 1900. For more on the change in Atlanta at this time, see Gregory Mixon and Clifford Kuhn’s, “Atlanta Race Riot of 1906,” in the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

This growth increased job competition among both black and white workers, and also exacerbated class distinctions. White elites feared the social intermingling of the races, and responded with increased segregation; the white and black neighborhoods were separated. The gubernatorial campaign in 1906 was especially inflammatory; both candidates (each of them white) accused each other of being too responsive to Georgia’s black citizens. During this campaign season, fear among white Atlantans, especially the perennial unfounded fear of black sexual violence against white women, led to attacks by white mobs on black citizens between September 22 and 24.

During these race riots, about forty African Americans were killed, along with two white people. A five-year-old white girl, named Peggy, was traumatized when she saw her father—who did not own a gun—stand outside his front door, holding an axe and an iron water key, ready to defend her against the supposed black assailants. The girl was Margaret Mitchell. She would become one of the nation’s first women journalists and author of Gone With the Wind. Margaret may have learned the wrong lesson from her experience; David O. Selznick’s 1937 movie version of her book was fittingly summarized for spectators with Ben Hecht’s opening intertitle:

There was a land of cavaliers and cotton fields called the Old South. Here in this pretty world. Gallantry took its last bow. Here was the last ever to be seen of knights and their ladies fair, of Master and of slave. Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered, a civilization Gone With the Wind….

(For those interested in learning more, the medievalist ethos of the elite culture in the South of the United States epitomized in Gone With the Wind has been explored by medievalists like Tison Pugh in his recent book Queer Chivalry: Medievalism and the Myth of White Masculinity in Southern Literature).

Medieval Atlanta

As Scottish and English immigrants formed the bulk of European immigration to the early South, these immigrants often considered themselves more British than American. They thus looked to Britain, and British self-fashioning narratives, for their cultural and social standards. Walter Scott’s medievalist novels like Ivanhoe and The Talisman, which romanticized the English court and an idealized portrait of “chivalry”, captured the early Southern imagination. And so, it was that the medieval knight, rather than the American pioneer, which became the Southern masculine ideal.

They linked themselves to the closest contemporary archetype of the medieval knight, the British nobleman—spawning the image of the “Southern gentleman”. This enabled the Southern aristocracy to rebuke newer (and Northern) “foreign” ideologies of materialism, feminism, and pacifism specifically because they seemed to be the very antithesis of honor, valor, gentility, hospitality, and chivalry. They created their own scaled-down version of what they saw as a medieval court: the Southern gentleman slave owner and his belle on their plantation. As Scott Horton wrote for Harper’s Magazine in 2007:

No doubt you learned in grade school that it started at Fort Sumter and that slavery and states’ rights had something to do with it. But no. The Civil War sprang with fully loaded double-barrels from the pages of Ivanhoe. No doubt about it.

It is against this general cultural background that Amos and Amanda’s Atlanta castle can be understood. It is a nostalgic architectural anchor to the bygone glory of the South, as well as Southern aristocratic culture’s deeply felt medieval roots. Like Walter Scott himself, who built for himself Abbotsford, a Victorian Gothic baronial home in 1824, they decided to inhabit a romanticized piece of the past in their own quickly changing and often threatening present.

A Confederacy in Stained Glass

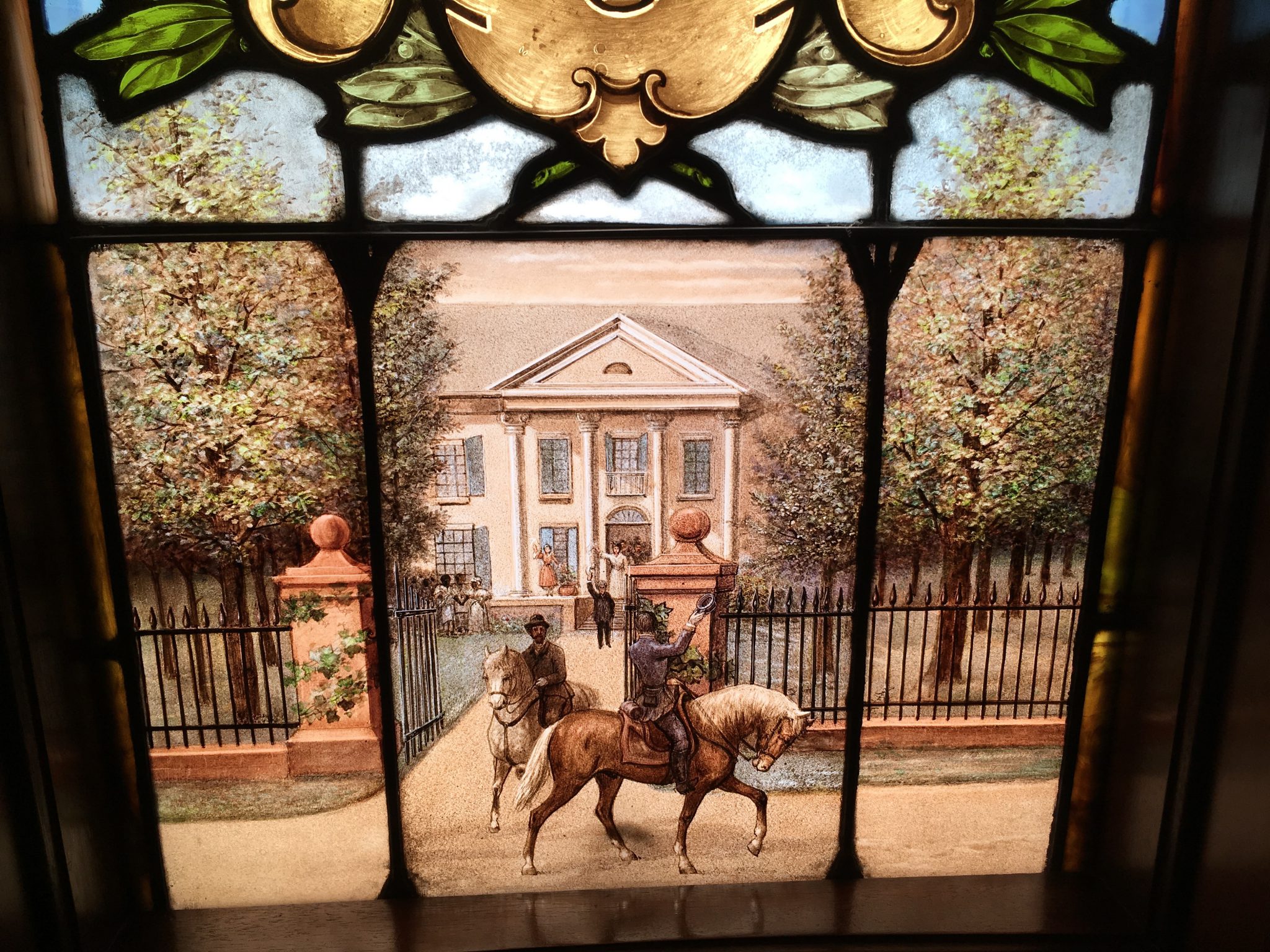

The visual and symbolic center of Rhodes Hall is a massive mahogany staircase which moves visitors’ eyes to a series of stained and painted glass panels. In these panels the owners and their architect created a church-like shrine to the “Lost Cause,” romanticizing the rise and fall of the Confederacy from the Battle of Fort Sumter (1861) to the Battle of Appomattox (1865).

The windows were executed by the von Gerichten Art Glass Company, who had been recognized with four gold medals for their craftsmanship at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair.

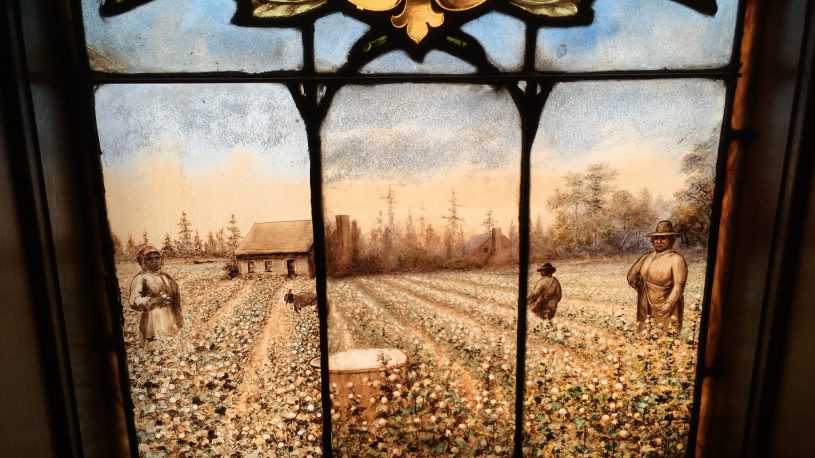

The glass panels consist of two longer sections depicting seminal historical moments, for example the election of Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederate States of America (1861), battle scenes, or other nostalgic moments of the Old South, interrupted by medallion-like portraits of Confederate politicians and generals. Each window is topped off by illustrations of abstract virtues like Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation, or mottos and seals celebrating various Confederate states.

The panels with scenes from the Old South provide eloquent commentary on the race relations in Atlanta in the early twentieth century. The many medievalizing gestures in Rhodes Hall serve to conflate the medieval and the ante-bellum past.

In one image (right), a Confederate soldier on a horse, probably an officer, gallantly waves goodbye to his wife, son, and daughter, who return his greeting. Playing in the dark, over on the left of a stately manor house and close to the shade of some trees, stand six black figures in white and beige worker’s clothes. They observe the departure scene without visible emotion. Their hands are at their hips or down on the side of their bodies, but their motionless and unfree status provides the symbolic backdrop in front of which the gallant manhood and freedom of the white male hero may be depicted.

In a second image, situated years later, a bearded patriarch on a cane stands by as his wife greets their son who, now on foot, has returned at the end of the war. Their yard is now overgrown with ivy and other

abundant flora, and an askew shutter on the Classical revival ante-bellum plantation manor hints at the fact that the place has seen better days. No slaves are to be seen anywhere.

If what can be inferred about Amos Rhodes’s taste for the Romantic and exotic in other rooms is any indication—his own favorite room features paintings with ‘noble native savages’ as idealized objects of another bygone era—he felt a deep yearning for a time when medieval knights and ladies, that is Southern gentlemen and their belles, and when medieval peasants and slaves, that is African American slaves, all knew their “rightful” place. Therefore, it is no surprise when the final of the three painted glass

scenes from the Old South shows what the Confederate officer was willing to fight and die for. It is a bucolic image of four African Americans occupied with providing the economic foundation for the Southern economy and lifestyle: King Cotton.

The packed basket up front and the ample future yield on the plants celebrate an agrarian and anti-industrialist economy which demanded ever more slave labor.

Only two generations after the American Civil War, the newly built Rhodes Hall still signified that legacy. The race riots of 1906 indicated that African Americans in Atlanta still had a long way to go to overcome the fortress mentality the monumental private castle enshrined.

Marriage in the Confederate Castle

What do today’s visitors know and think about the interplay of race and medievalism in Rhodes Hall, about six generations after the Civil War? Couples who get married there often explain on Facebook:

“It’s a nice place with some history to offer;”

“I felt as though I had slipped into Downton Abbey.”

“I reccomend [sic] this venue to anyone who wants a unique and historical feel to their special day!”

“Thank you for allowing me to literally walk into history in my own state.”

Clearly, the sense of historical distance, the “alterity” (if you will) of Rhodes Hall is all they are looking for. They accept the celebration of the “Lost Cause” as something bygone that happened sufficiently long ago not to stay away.

The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation, a non-profit organization, has a long-term lease agreement for Rhodes Hall with the State of Georgia; it is doing an excellent job at maintaining the historic building. It prefers to advertise this innocuous level of alterity. Their web site focuses on how the recent renovation efforts have included “Going Green”. Descriptions of the building’s history avoid potentially sensitive contexts, and rather focus on Rhodes Hall’s representative character for what is summarized as Atlanta’s “belle époque”. Of course, the saintly-looking generals that wedding photographers inevitably capture include fervent opponents of reconstruction (Robert Toombs, 1810-1885), a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan (Nathan Bedford Forrest, 1821-1877), and the head of the Ku Klux Klan in the State of Georgia (John B. Gordon, 1832-1904). The political and racial views that guided these Georgians’ lives and careers, while no longer officially tolerated, continue to haunt race relations in Georgia. Recent events in Dahlonega, GA, perhaps encouraged by the national political climate, make this abundantly clear.

Time for a Change?

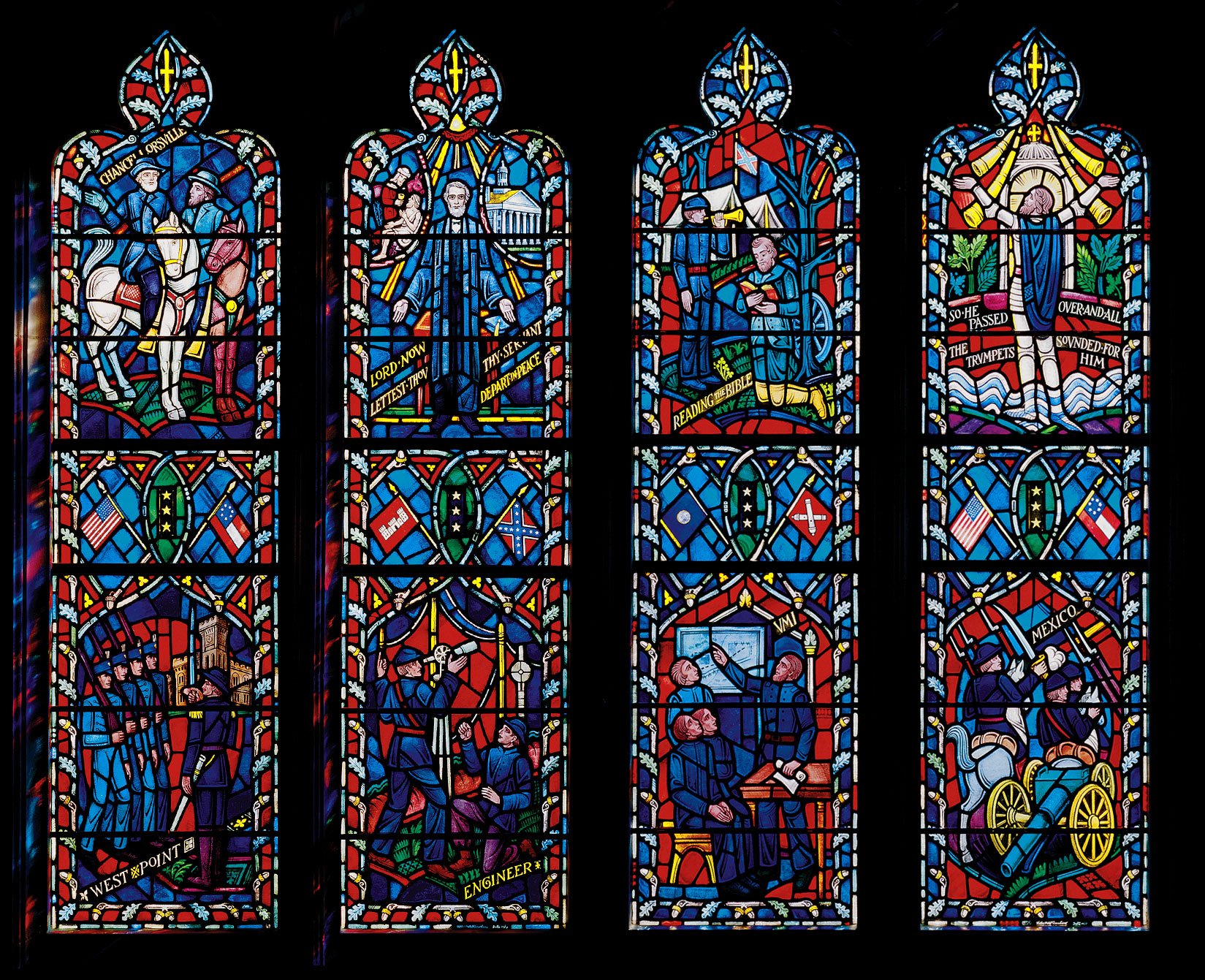

Could those in charge of Rhodes Hall profit from others’ best practices to deal with this complex situation? For example, in 2015, the leadership of Washington National Cathedral decided to deal with a series of Confederate War-themed stained-glass windows in their place of worship. The windows depict Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, featuring images from the lives of the two generals and implicitly representing them as exemplary Christians. This causes an obvious problem for the contemporary members of the cathedral’s congregation.

Cathedral leaders agreed to remove and replace with plain glass any Confederate flag images in the windows. These images were originally installed in 1953 after lobbying by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (an organization founded, incidentally, ten years before the construction of Rhodes Hall and similarly dedicated to heroic readings of the Civil War and the “Lost Cause”). However, before executing any changes, Washington National Cathedral resolved to make this process a public moment of communal learning, with various discussions and presentations for more than a full year. As the Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, the Cathedral’s Canon Theologian, states on the cathedral website:

Instead of simply taking the windows down and going on with business as usual, the Cathedral recognizes that, for now, they provide an opportunity for us to begin to write a new narrative on race and racial justice at the Cathedral and perhaps for our nation.

And in 2015, the Very Rev. Gary Hall, then dean of the Cathedral, told NPR that the cathedral leadership was “not trying to whitewash our history” but rather

to celebrate our history. But since the cathedral tells the story of America, and just as America is trying to come to terms finally with the Civil War and slavery and racism and segregation, it seems to me that it’s more appropriate for us to have windows that tell that story in all of its complicated fullness than just present a kind of public relations picture of a couple of Southern generals.

Might it be time for Rhodes Hall, the Georgia Trust, and the city to engage in similarly public discussions about the conspicuously medievalist building on Atlanta’s Peachtree Street? Since it is not a place of continuing worship, but a former private residence now in the public trust, there is no need for removing or even “emending” the windows. Any public discussions, some of them undoubtedly controversial, would not end the attraction for those who would like to celebrate their wedding as part of the entrepreneurial “Cupid at the Castle” project. However, these discussions could contextualize Rhodes Hall’s historical alterity in more responsible and socially productive ways.

Note: I am grateful to Dr. John Turman, former tour guide at Rhodes Hall who, on May 14, 2013, provided me with a list of all scenes, symbols, and individuals depicted in stained and painted glass.

The Public Medievalist does not pay to promote these articles, so we would love it if you shared this with your history-loving friends! Click to share with your friends on Facebook, or on Twitter.

Comments are closed.