Reigns is a medieval monarch simulator game for smartphone and PC by Devolver Games. Currently selling for £1.99, it’s worth a look (and is a cheap gift). I’ve sunk an alarming number of hours into Crusader Kings II, the Total War and Civilization series (and other medievalesque strategy games). So, I thought this would be right up my strategic alley. And I was right. Reigns is awesome in many ways.

Reigns is an altogether different beast from these other series. It doesn’t have anywhere near the mechanical depth of Grand Strategy games like Civilization VI. But that’s not a problem. In fact, the game has been widely praised for its simple mechanics. Sure, Reigns is entertaining. And we can go further than that: despite being a relatively simple game developed for smartphones, Reigns is also a great simulation of the core of medieval rule. And more, it has a surprisingly compelling message about the Middle Ages.

Better to Reign in Hell

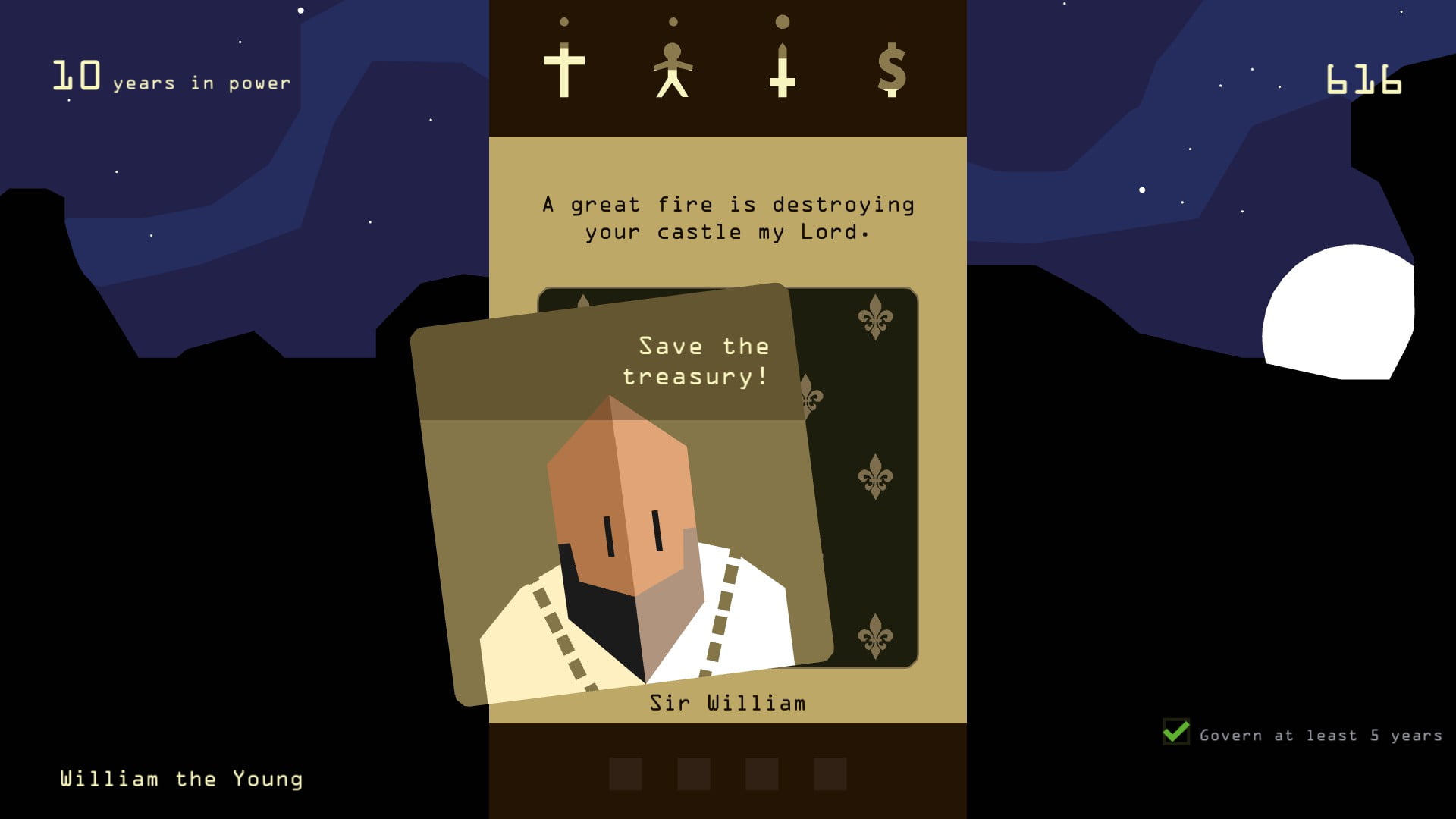

Reigns is built around two key mechanics. The first of these are decision cards. Every year of your reign, you turn over a card and are presented with an issue. You are then given a binary choice as to how you solve it (and, in Tinder-esque form, you do this by swiping left or right on the card). There’s a fire in the capital! Do you save the army, or the treasury? A wandering preacher arrives at the castle gates! Do you invite him in, or burn him as a heretic?

Many of these decisions have long-term consequences. Some lead immediately to other cards, and others unlock new cards that appear later, introduce new characters, or progress the plot.

Almost all of these decisions influence the second mechanic. Your kingdom has four meters: the Church, the peasants, the army, and the merchants. Each of your decisions will cause one or more of these ratings to change. Did you save the army in the fire? Your military meter will go up, but since your treasury goes up in flames you lose some support from the merchants. Did you let the wandering preacher in? The peasants are pleased, but the Church begins to question your piety.

As king, you must keep all of these elements in balance to retain your throne. If your military rating drops to zero, your kingdom will be conquered by your rivals. At the same time, you cannot allow any of the ratings to rise too high—if the military become too powerful, they will stage a coup and depose you. When (it’s a definite when—you’re going to be overthrown a lot as you play) you start over with your heir, your ratings reset back to the middle.

Under normal circumstances (with one exception that involves eating some strange coloured fungi) the extent of the impact of each decision you make is obscured. You get an indication of which ratings will be influenced, whether it will be positive or negative, and whether the impact will be great or small (no precise value, just a binary big or little). As you also don’t know the precise value of any of your current ratings, the game can get surprisingly tense as you try to prevent the various factions from destroying you horribly.

It’s Tough to be King

This leads to some interesting gameplay and delicate decisions. In order to keep your throne, you may have to do some pretty awful things. I found myself failing to prepare adequately for an invasion and allowing my peasants to suffer terribly, because throwing more funding at the army would have allowed the general to overthrow me. Later, to appease the Church, I had an inordinate number of my peasants burned as heretics and had advanced medical techniques banned as sacrilegious.

By all accounts, this should feel like a straitjacket. You have to make snap decisions along restricted lines. There are no third options. In order to keep the different factions in line, you often have to act erratically, supporting one side then another. You can’t present reasonable compromises.

But this makes the game work. The simplicity and speed of the gameplay takes the edge off the binary choices. Moreover, when your king dies, you just continue immediately with his heir. This removes most of the sting from an inopportune decision. There is very little that carries over from one king to the next, so despite the apparent pressure, the stakes aren’t too high. The variety and humour of the decisions cap this off; you’ll probably get through a run before the game starts wearing thin.

Royal Realism

More importantly, these elements of the game give represent medieval rule in a way that isn’t really matched by the more complex king-sims. The decisions you make here come at you fast. Their impact is immediate and often decisive. You don’t have a codex of useful statistics to consult, or in depth mechanics to master and exploit. You just get a rough idea of what each decision will do, just like a medieval ruler.

The light roleplay elements—each card is sketched as an interaction with a member of your court—are also important . They better represent the decisions and consequences that are often weirdly abstract in Grand Strategy Games. Telling a peasant that you’re cutting their food supply is very different from moving some icons around and seeing numbers change when you hit ‘end turn’.

Warfare in Reigns is also very peripheral to most of the gameplay. This also encourages the player to play like a real king. Wars will happen, and your decisions will affect their outcome. But military activity is a relatively minor part of Reigns, as it was for many medieval monarchs. Wars impact each section of society, they’re not just a means to conquest. In fact, in Reigns, as often was the case in the actual Middle Ages, there is no conquest. If you win a war, some of your ratings are adjusted and play continues. This stands in stark contrast to your typical king-sim where warfare and conquest are, almost inevitably, the goal.

The lack of permanence between kings also is a bit closer to how medieval kings actually behaved. There is almost no long-term planning in the game. Most decisions will not impact anything beyond your current reign. The few exceptions (introducing new characters, constructing a handful of buildings, and advancing the plot) are significant because of their rarity. Medieval kings acted in a similar manner: sure we see dynastic planning, but never on the millennia spanning scale of typical Grand Strategy Games, and this long-term thinking often took a back seat to immediate problems. Just like medieval kings, the player is forced to focus on the short-term even as they try to make use of longer term plans.

All in all, Reigns does a lot of good in simulating the life of a monarch. It’s abstract, and has a lot of silly elements, but it really captures the essence of medieval rule. It’s all about staying on top no matter the price.

So Reigns is great, doesn’t overstay its welcome, and teaches a bit about real history, perhaps in spite of itself. End of article.

…

Okay, okay, it’s not perfect. Let’s start by splitting hairs. The narrative isn’t always remotely medieval. There are elements of modernity (colonisation of a pseudo-American continent) and elements of fantasy (is that… is that a dragon?). On the surface this isn’t really an issue. It doesn’t hurt the medievalness of the core mechanics of the game. It certainly doesn’t hurt the play of the game. It’s generally entertaining stuff.

The problem with the narrative is it gets repetitive pretty quickly. There are a finite number of cards. You’ll start seeing some of them again and again before the end of your first playthrough. Even with the expansion, you’ll start to feel like you’ve been through a lot of this before even as you get into your second run.

To a certain extent, this is fair. There’s only so much content that you can squeeze out for a game this reasonably priced. The expansion DLC represents a valiant attempt to address this issue by the developer. Furthermore, I’m pretty convinced there are still cards that I’ve not seen—and seeing the same card twice is hardly a problem as it lets you find out what happens if you decide differently.

It’s not a Bug, It’s a Feature

The repetition of cards and decisions actually ties in well with the overall goal of the game. See, the plot of the game, beyond the balance of power within any individual reign, is to help (over the course of many reigns) your kingdom to escape the endless cycle of the “dark ages.” You only have a set number of years to accomplish this, at the end of which you either succeed, or fail to break the curse. You are told this at the start, and at various points during the game. And, in the default ending it gets laid on pretty thick.

The problem is that this ultimate goal is fairly easy to miss. Despite the opening brief and reminders periodically throughout the game, it’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day strategy and comedy of running your kingdom. It’s not too hard to completely forget about the goal only to be rudely awakened at the end of the game.

You’re going to need a second run through to succeed. The solution to the game requires several specific conditions to be met. This in turn requires a certain specific sequence of cards to come up—and they might never do so. So your victory can ultimately be in the hands of the Random Number Generator.

Losing is Fun

Figuring out how to escape the cycle is difficult and requires thinking outside the framework of the game mechanics. You have to think differently, pay attention, and—no spoilers—have a breakthrough moment of enlightenment.

Putting this into practice is likewise difficult, but for different reasons. You have to play in a different way with a different focus. You need to act like the quintessential Renaissance Man—or at least, the way that “Renaissance Men” liked to think of themselves—looking to change the nature of his world. You must move on from being a Medieval “barbarian” trying to succeed within the existing “backward” setting. However, in doing this, you will encounter the same events repeatedly, you will be distracted by the core gameplay and achievements that this drives, and you will be constantly frustrated by factors beyond your control.

This is an excellent analogy with the way that popular histories have depicted the Enlightenment: new thinkers with new ideas enduring great hardships to drag their fellows out of the Dark Ages. It’s a powerful analogy, and coming from such a simple game it rather blindsides you. It’s still frustrating to see victory escape you for the fifth or sixth time, but at least it feels like there’s a bigger message here.

Jacob Burckhardt was a Hack

The real problem though isn’t how the game sells its message, which it does very well, but what that message is. The idea of “the Dark Ages,” that the Middle Ages was a period of stagnation and darkness, is outdated. It’s a hangover from the historians of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, from Emmanuel Kant to Edward Gibbon to Jacob Burckhardt, They needed to present history as fundamentally about “progress,” in order to justify their personal and political worldviews.

The idea that people were “trapped” in the Middle Ages is a major issue. A medieval stasis which could only be broken by the great and revolutionary thinkers of the Enlightenment meshes with colonialist arguments justifying the exploitation of “backwards peoples” by more enlightened Europeans. This idea of “progress” was weaponized against those whom European imperialist projects around the globe targeted for exploitation or extinction. So, when I say that the idea of the “Dark Ages” is outdated, I don’t just mean a quaint relic from the past: it is a key part of racist, imperialist, and colonialist ideologies.

The very phrase “Dark Ages” is emblematic of this idea (how are you going have an enlightenment if it’s not dark to start with?). Study any medieval history and you see this is not the case. We see in the Middle Ages scientific, economic, architectural, agricultural, and social changes which moved us closer to the present day. The Italian Renaissance happened in the Middle Ages. People in the Middle Ages did not believe the world was flat. The first Universities were founded in this period. Outside Europe, the Islamic World, parts of Africa, and China went through cultural, technological, and economic Golden Ages.

A lot of the negative aspects associated with the Middle Ages are either remnants from the ancient world (a lack of core medical concepts, alchemy and other weird “science”) or didn’t happen until the modern period (burning witches, using leeches, and yet more comically bad medical practices). Moreover, by ascribing modern atrocities to the Middle Ages, Reigns falls into a typical contemporary pattern: anything horrific in the modern world—from violence, to stupidity, to online abuse—is described as “medieval,” distancing it from our world and excusing us from viewing it as our problem.

The message set out by the core mechanics of Reigns runs completely counter to current thinking on the Middle Ages and feeds into a narrative which permits some very negative uses of the Middle Ages in the modern world. The game is far from the worst offender in this regard, but it’s certainly part of this overarching issue.

Could Do Better?

I anticipate there being a couple of responses to this. Let me head them off at the pass.

“But it’s only a game. It’s not meant to be taken seriously.” That’s an awful excuse and it infantilises the medium. If we want better games, we need to stop seeing them as facile things. Reigns is not a silly game. It has silly elements, but a very serious core. Reigns does a great job of dealing with a complex idea using very basic mechanics. Unfortunately, the idea is demonstrably removed from reality and forms part of a harmful cultural weapon.

“But it’s art. It doesn’t have to conform to reality.” That’s only slightly better. The emergence of the world from a Dark Ages is a good story. It provides a nice strong foundational narrative for the game in a way that “the Middle Ages were a period of sporadic but steady progress and led seamlessly into the modern world” simply cannot. Deviating from history in this fundamental manner may be a net benefit to the quality of the game. It’s problematic in the broader scheme of events, but makes perfect sense for the game itself.

But that’s the thing: Reigns inadvertently ends up feeding harmful misconceptions about the Middle Ages. There’s not any malice behind this, and this is certainly a mirror of typical modern attitudes towards the period. It a drop in the bucket of a harmful cultural misconception.

This is a mis-step, especially considering the efforts made by the designers to counter the glorification of many of the troublesome themes it addresses. In the game, crusades and colonisation not only force the player to deal with some uncomfortable decisions, but actively make it harder to control the kingdom. To win the game you have to engage with social outsiders, become part of a revolutionary conspiracy led by a woman, and encounter knowledge and technology from the game’s version of the Middle East. The sequels, Reigns: Her Majesty and Reigns: Game of Thrones take this social commentary further (and are also worth a look if you enjoy the original). I’m also intrigued by the forthcoming tabletop game

To sum up then: Reigns is great fun. On the surface, it’s a strong, but abstract, simulator of being a medieval monarch. As you dig deeper, there’s an important message about the nature of the Middle Ages, and its place in the broader span of history. This message fits perfectly within the game’s story and mechanics and makes for a very interesting story told in an innovative way. The game demonstrates how simple mechanics can be very effective in creating a space for both play and story. It’s just unfortunate that this story doesn’t match the medieval reality and that it reinforces harmful trends in modern popular thinking. It could do better, but it’s still a great and innovative game which is definitely worth a look.