Since its origin in the mid-80s, Capcom’s Mega Man franchise has been one of the most popular and recognizable properties in video games and other media. There have been sequels and spin-offs, but the most enduring part of the franchise remains the classic series. In these games, you play Mega Man, a blue robot adapted from a lab helper into a heavily-armed fighting machine. Mega Man fights against the evil Dr. Wily and the “Robot Masters” he has built or suborned. The player navigates their way through stages themed to each Master before fighting it in a standard-issue 1980s video game boss fight.

Mega Man’s gimmick is that, when you beat a Robot Master, you acquire an iconic weapon related to that Master. Each weapon you acquire is is particularly effective on one other Master. For example, in the first Mega Man, when you defeat Ice Man you get his weapon, which you can then use to take down Fire Man, whose weapon takes down Bomb Man, and so on. This creates a rock-paper-scissors dynamic that has been extended and elaborated through the whole series.

But what has this got to do with the Middle Ages or medievalism? Mega Man is obviously science fiction, with its futuristic setting and gleeful robot carnage. But it turns out that some key elements of the Mega Man games are driven by popular images of the medieval.

Knight Man, one of the eight Robot Masters of Mega Man VI, embodies this. Each of the Robot Masters and their stages are renderings of stereotypes of places and cultures intermixed with the large-eyed robots and other stylistic flourishes typical of Japanese sci-fi Manga art. Knight Man’s appearance, conduct, and environment offer various examples of cross-cultural use of the European Middle Ages by Japanese developers (a topic that demands more attention than can be given it here) alongside a range of medievalist tropes.

The Master of Mace Ball

The game’s designers get a surprising amount right about medieval knights. Knight Man certainly looks the part. His emblazoned shield reflects fairly common knowledge about knights. But his armor (consisting of crested barbute-style helm, spiked pauldrons, cuirass, cuisses, poleyns, greaves, and sabatons) suggest more detailed research and a deeper understanding. Even his weapon, the spike-ball mace aligns with our knowledge of knightly combat gear.

Knight Man’s position in the game’s rock-paper-scissors gimmick also ties into our understanding of the medieval knight. Knight Man is weakest against the Yamato Spear (which Mega Man receives by defeating Yamato Man). Heavy cavalry, like knights, were sometimes defeated by spears—as dramatized in the Battle of Sterling in Braveheart.

In some places though, the presentation of Knight Man leans more heavily on popular perceptions of the Middle Ages than on the actual past.

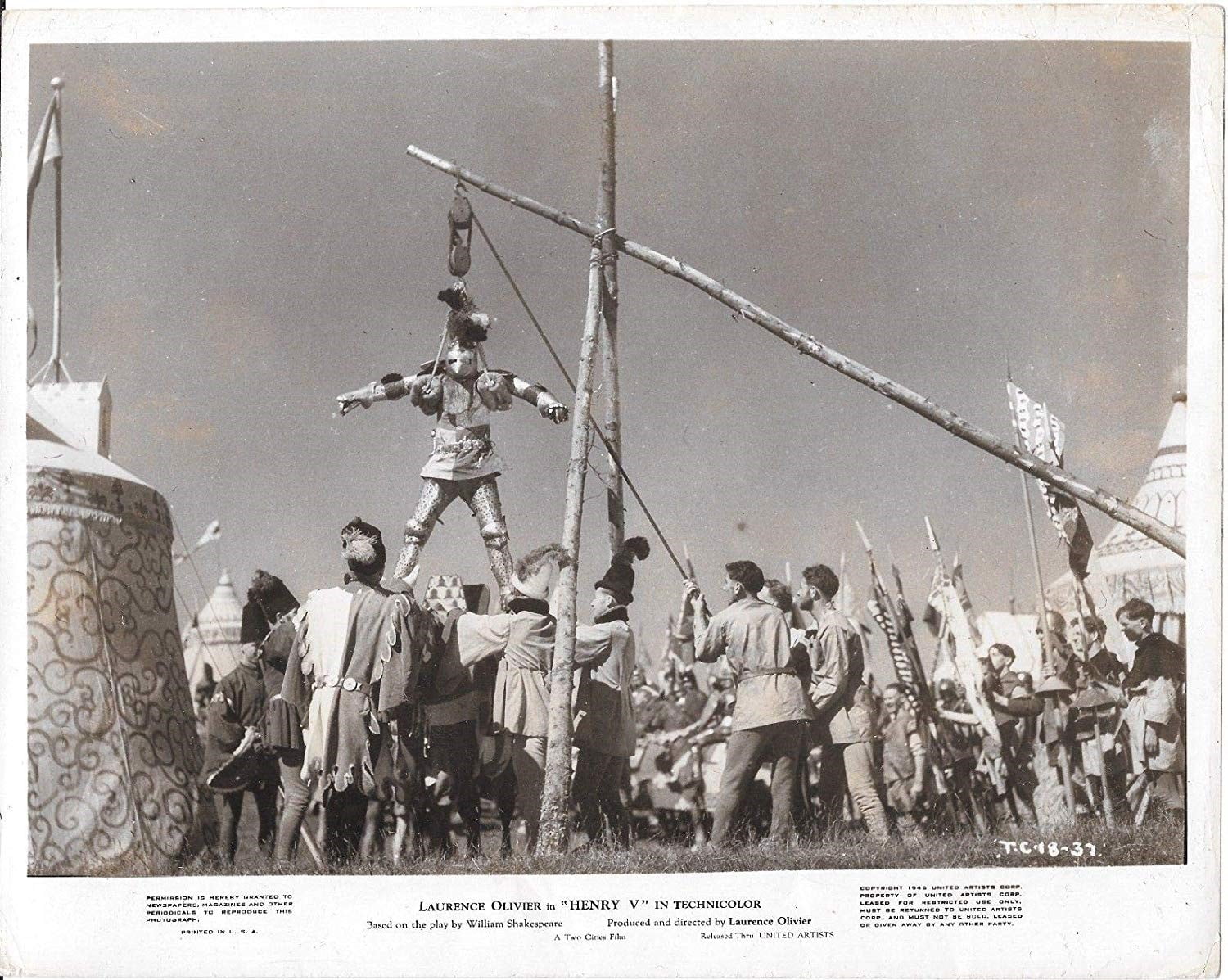

Knight Man’s stats present him as large, heavily armored, and not terribly mobile. They portray him much like the caricatures of towering knights having to be winched onto horseback in the 1940 Lawrence Oliver film version of Henry V.

This image of the medieval knight as heavily armored, slow, and clumsy pervades the popular imagination. Unfortunately, it’s almost entirely wrong. As Daniel Jaquet’s 2016 short film shows, a 34-year-old “knight” in full armor can move as well or better than a 24-year-old soldier in modern military gear. Knights probably carried less weight than modern soldiers, and it was distributed more evenly around their bodies.

Curiously, in the game, Knight Man moves around in ways that challenge this stereotype, and his stats screen. During his fight with the player character, the purportedly less-mobile robot displays boggling maneuverability, leaping high into the air and tossing his large, spiked-ball mace about with ease.

While it is possible to conduct some pretty impressive acrobatics in this kind of armor, it isn’t really practical in battle, and it comes nowhere close to the feats performed by Knight Man. The game presents a stereotypical view of the heavily armored and clumsy knight through its statistics screen, but goes to the other extreme during gameplay, granting Knight Man implausible agility.

There’s also the matter of Knight Man’s weapon. The game calls it a mace—a weapon more like an improved club than anything else. This early version of the lead pipe was standard knightly equipment, designed to deliver heavy bludgeoning blows which could cause substantial trauma even through heavy armor.

But in the game Knight Man’s weapon works more like a flail—a ball on a chain. Knight Man attacks by launching his ball towards the player before pulling it back towards himself. The weapon is associated with the European medieval, but it saw little if any use there as a weapon of war, as Paul Sturtevant notes here and here. Again, the game combines elements of the medieval with popular misconceptions.

Knight Man’s use of his shield likewise combines accuracy and misunderstanding. While he does use his shield defensively, it is only as a passive defense, held firmly in front of Knight Man to repel almost everything Mega Man can throw at him. Knight Man does not reposition the shield to intercept attacks. Nor does he use it in an offensive capacity—a shield bash or shield rush—as medieval combat manuals suggest.

The fighting technique that Knight Man uses is substantially different from medieval combat styles. While knights moved about in their work, they tended to make more use of their materials (their armor and shields) than Knight Man does—and less of acrobatics.

Some of the issue doubtlessly lies in programming limitations. The developers worked wonders with what little memory they had, but there’s only so much 8 bits can do. Beyond this, though, the developers clearly deployed medievalist tropes without necessarily looking to the medieval for correction and insight. Their depiction of Knight Man comes from the popularly known medieval without looking much to the actual medieval.

The Master’s Domain

Knight Man’s level is a perfect metaphor for the game’s presentation of the medieval, something that leans more on modern tropes and perspectives than actual history. As the stage begins, the protagonist teleports onto the roof of a castle in the woods at evening. Braced rough stonework, complete with crenelations, appears in both the foreground and the near background.

From the start the stage design calls out to the popular image of the medieval: the castle. Knight Man’s castle leans on the storybook, fairy-tale form of Disney movies and the Gothic presentation of decaying remnants of the medieval Europe. So far, so medievalist.

But as the stage continues the medievalist portrayal starts to unravel. Mega Man proceeds into a basement filled with pipes of unknown purpose, which would be more at home in an industrial installation or cyberpunk factory. To be fair, the game takes place in a future populated by autonomous humanoid robots, so the environment fits with the game.

But these pipes don’t fit with the medieval flavor of the rest of the level. Despite common perceptions of the Middle Ages as a time of dirty peasants, medieval plumbing was a thing. But the piping employed by builders in the Middle Ages was not of the sort seen in Knight Man’s castle. The stage’s pipes look more like science-fiction energy conduits (fitting, given the franchise) than the outflows of garderobes.

The rest of the stage moves back and forth between medievalism and science fiction. Stonework overlays or replaces background conduits, and lit torches offer a “more authentically medieval” cast to portions of the stage. These elements are juxtaposed with the moving floors and the occasional bits of conduit that still poke out amid the shaped stones that line the level.

The medieval nature of Knight Man’s castle is a thin, decorative veneer. The shallowness of this medieval skin becomes more obvious as the level goes on. Breaks in the background stonework reveal connected conduits that move away at right angles before vanishing behind foreground features, and the foreground stonework is increasingly intermixed with futuristic floors and ceilings. If the medievalism in the level is a veneer, it thins out and cracks repeatedly, more and more so as the stage progresses towards its end, a perfect metaphor for the game’s treatment of the medieval in general.

Knight Fight

The boss fight with Knight Man also draws on medievalist tropes, but these come from a different point of origin: later medieval authors writing about earlier medieval heroes.

The stage ends in Knight Man’s own chamber: a large, open room with banners and balconies worked in stone which corresponds to popular expectations of the rooms of a medieval lord. To be fair, actual medieval feast halls and throne rooms were large and imposing, reflecting the importance of those who owned them and their role in the business of government.

But in the popular imagination the size of such rooms reflects their potential as impromptu arenas for climatic fights between the noble hero and evil villain. Their size reflects the importance of the victories they will see and the gravity of the events which will occur within them.

These modern expectations exist because they have precedent in medieval literature. The opening of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight—the decapitation of the Green Knight (he got better) by the noble Sir Gawain—takes place in King Arthur’s feast hall. In Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century Arthurian tales (Le Morte d’Arthur), Arthur’s court is the setting for countless duels, brawls, and other acts of violence. In Beowulf, the titular hero’s fight with the villainous Grendel rages through Heorot—the imposing mead hall of King Hroðgar.

In fact, the concept of struggling through a series of lesser enemies towards a climatic boss fight is firmly medieval. The tale of Beaumains within Malory’s work is a good example. The titular knight fights his way through a series of color-coded lesser adversaries (the Black, Green, Puce, and Indigo knights) before facing and defeating the mighty and fearsome Sir Ironside, the Red Knight—and clearly Beaumains’ level boss. Parzival’s (Percivel’s) early adventures in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s works function in a similar way. So do many of the fairy tales and adaptations of them that inform popular concepts of the medieval. Knight Man’s stage follows a broadly similar pattern to any number of medieval tales.

But the thing is, these knightly and heroic tales are clearly fiction. They are medievalist tropes used by medieval authors, but they are still medievalist tropes. Malory and the other later medieval authors gleefully imposed the ideas and ideologies of their own time on the earlier medieval periods they described. They used popular ideas of the early medieval to tell their stories. Actual events were an afterthought.

The climatic fight with Knight Man makes use of the same medievalist tropes as these later medieval authors. Mega Man undertakes a perilous quest, defeating the underlings of his great adversary, before confronting and defeating this evil knight in a climatic battle in the throne room.

Why It Matters

Knight Man is a good example of the typical use of European medievalist tropes in popular media. His portrayal borrows from popular perceptions of the Middle Ages without looking too much into actual medieval world. The developers present the medieval as being something used to decorate rather than as an amalgamation of rich, full cultures. As such, they minimize understanding of and engagement with that part of the past.

It is true that the game is “just a game.” An 8-bit side-scrolling platform game does not need terribly rich detail, and cross-cultural borrowings can generally take more artistic license with their sources than can those from the cultures of origin (as I’ve argued here). It’s also true that Knight Man is far from the most heinous misrepresentations of the Middle Ages. Still, the game’s clumsy use of the European medieval is not to its credit.

Popular media presentations like the Mega Man games inform much public understanding of what the medieval was and is. If nothing else, repeating information sets up expectations of what is real or realistic. As such, every iteration of wrong information, every instance of inaccuracy, perpetuates misconceptions and closes off avenues of understanding that much further.

Furthermore, games like Mega Man were openly geared towards children. When people are taught early on that things are a certain way, it is all the harder for those who will teach them later in life to ensure that, as they grow up, they proceed from a sound and solid understanding of what was as they work toward what they will be. Even such idle pastimes as video games can have a deep and lasting effect on their players.

The shallow and clumsy use of the Middle Ages in Mega Man isn’t an obvious problem. But, like the issues within Game of Thrones, it forms a foundation for more troubling portrayals and abuses of the medieval world. Perhaps by addressing the formative misunderstandings presented by Mega Man and other games, we can go some way to countering such bigger issues.

All game images taken from PinkKittyRose’s playthrough of the level on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4Npy6QWwLY&t=35s, used for commentary.