Content notice: This article includes spoilers for the 2018 game God of War, includes discussions of some pretty grisly video-game violence, and a spoiler for the end of the world.

The first three God of War games were a series of action adventure blood-fests set across the mythological landscape of ancient Greece. They focus on a Spartan warrior named Kratos. Kratos was deceived by the god Ares into murdering his wife and daughter, and the games detail his hyper-violent, trilogy-spanning rampage of revenge. In it, he slays Ares, taking on the mantle of ‘The God of War’ (God of War, 2005). Kratos then betrays and manipulates his way through Greek mythology. He literally takes the will of the Fates into his own hands in an effort to change his past and reconcile his future (God of War II, 2007). Unsuccessful in his attempt to restore his former life, Kratos resorts to killing Zeus (God of War III, 2010). In the end, after murdering nearly the entire Greek pantheon, Kratos escapes to the North. Alone.

It seems tailor-made for a student who was very annoyed at being made to read the Odyssey in literature class.

These games were among the biggest success stories on the PlayStation. They were widely acclaimed, with particular praise for their groundbreaking graphics and the size and majesty of Kratos’ opponents. The core series also spawned a series of spin-off games, as well as a growing number of clones. Kratos has also appeared in a range of fighting games including Soulcalibur: Broken Destiny and Mortal Kombat as well as some more unexpected appearances such as in Hot Shots Golf: Out of Bounds; among many console gamers, Kratos is a recognizable character alongside the likes of Lara Croft, Snake, Master Chief, or even Mario. At the same time, the games have attracted criticism for their explosive violence, portrayal of women, and Kratos’ lack of morality.

The new God of War (2018), is the fourth game in the series, but could stand on its own as the start of a new trilogy. This God of War gives the player a vast new mythological world to explore, by dramatically shifting the setting from Ancient Greece to Early Medieval Scandinavia.

There is much to be gained from seeing Kratos’ Viking Odyssey as a continuation of his earlier exploits. The themes of relic-objects, mythological weapons, magical abilities, and Godly Possessions so vital to the first games are continued, albeit with a specifically Norse flair. In this game, Kratos is still physically identifiable as the Greek Kratos, due to his red tattoos over his face and left shoulder. The improved graphics makes the game look more real, and Kratos more human. He was supernaturally exaggerated in the original trilogy, though Kratos does still look out of place in this new world.

The game plays on this tension between the old Kratos and his new environment to create a very different storyline. In the North, Kratos falls in love with a Scandinavian woman, Fey (or Laufey), with whom he has a son, Atreus. Kratos continues to wrestle with his colossal “anger issues” while adjusting to his new life. But he is no longer the vengeful antihero of the earlier games of the series. He’s a father. He has a child in tow. His mission is now to honor his lover’s final wishes.

Kratos may not be a ‘good guy’. But we see that he seeks to be a different man throughout the game. This struggle to become something other than his past feeds into the game’s structure and is tied to the Norse mythology that the game intersects with.

Like Father Like Son?

The game opens with Kratos and Atreus mourning the death of Fey (Laufey). The game’s plot is a simple one; you are tasked with spreading Fey’s ashes atop the peak of the highest mountain in all the nine realms: the lands of Norse mythology where the game takes place.

While Kratos and Atreus both clearly love Fey, they treat the mission, and the world around them, very differently. At first, Kratos sees little use in the knowledge of the runes or the stories about the Scandinavian world that Atreus tells him. Kratos is wary of possible threats and would rather consider everyone and everything an enemy, while Atreus is eager to learn anything and everything from anyone. The tension between them along their journey fuels much of their character development.

This journey requires various interactions with characters and themes of Scandinavian mythology: the nine realms, the tree called Yggdrasil, the various types of beings like Elves and Dwarves, and the magic of runes. Fey created a series of protection runes, or staves, on trees around the home she shared with Kratos and Atreus. These staves are clearly inspired by Nordic runes.

Unlike Kratos’ murderous vengeance in the earlier games, his goals in God of War are not inherently violent. Kratos is simply wants to mourn and honour his dead lover. His desire to remain unknown seems to have fueled his calmer nature in this northern climate.

Nevertheless, the significant majority of beings encountered are enemies that you must fight to progress the story. In fact at face value, God of War seems like a series of basic hack-and-slash challenges with some puzzle-solving mixed in for good measure. This is very similar to the first three games.

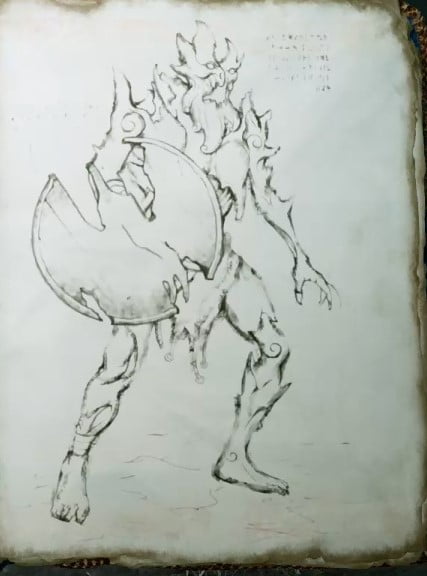

This gameplay seems also to feed into a traditional “good vs evil” story. For many stories from the European folklore traditions there are clearly defined “heroes” and “villains”. God of War follows a basic progression where the hero battles a series of increasingly powerful villainous opponents. In this case, the evil characters are often monsters connected with the idea of death. The dragur are half-dead warriors; Nightmares or Revenants also reference dying. Even to players unfamiliar with Scandinavian mythology, these creatures immediately scream “bad guy.”

But beyond this superficial layer of black-and-white morality, the game’s dialogue and narrative point to a more complicated moral structure. Over the course of the game, “good” becomes murky indeed. To really get to grips with the ethics of God of War, we need to look at the game’s source material: Norse mythology. And the two key sources for our understanding of Norse myths are the medieval Prose Edda and Poetic Edda.

Talking to Strangers

Immediately after Fey’s death, Kratos encounters a man identified only as “The Stranger.” The Stranger, covered in tattoos, hair tied up with beads, and wearing a pair of baggy trousers, looks like he could have been pulled straight from one of the characters from the popular TV series Vikings. His maniacal and condescending tone pushes Kratos’ buttons, and they clash, resulting in the first “boss battle” of the game.

This is the first time that you, as the player, interact with someone. This particular stranger’s physical appearance is full of clues about his identity and the nature of the world. The Stranger comes looking for information from Kratos and “whoever he is hiding” (Atreus) in his house. It is clear The Stranger has an idea about who Kratos is and wants a battle to determine his power.

But who is The Stranger? There are a couple of clues, at least for a medievalist such as myself. Firstly: his tattoos. The band of runes across his left chest plate is particularly important. They read as “ek er daudi“: roughly: “I am dead.”

Secondly, throughout the battle The Stranger alludes to his inability to feel anything. He heals himself mid-way through the battle, and you can’t kill him with brute strength. He is, effectively, impervious. The fight ends in a grotesque style that has become the hallmark of the series: Kratos snaps The Stranger’s neck and throws him off the side of a cliff, assuming him to be dead.

However, this isn’t the last time we see The Stranger; he’ll be back to “killed” by Kratos repeatedly throughout the game. The Stranger is, effectively, invulnerable and immortal, but also somehow already dead.

The only god in Norse mythology that fits this image is Baldr, the son of Oðinn and Frigg. In the traditional Norse mythos, the infant Baldr was prophesied to die. His devastated mother persuaded every living thing to swear not to harm her son, leaving Baldr impervious to harm. But Frigg neglected to secure a promise from mistletoe because it appeared so harmless. In the Prose Edda, Baldr is ultimately killed when Loki tricks the blind god Höðr into shooting Baldr with an arrow made of mistletoe. Baldr ultimately resides in Helheim, the land of the dead, until the completion of Ragnarök.

It’s the End of the World as We Know It.

But why open the game with Baldr? He is not the most recognizable character from the mythos; he’s no ƿórr (Thor) or Oðinn or Loki. But he’s also not just a throwaway tutorial god that would allow the player to learn how to handle the game. Baldr has an important role in Norse mythology, and his death is the first of a series of events which will lead to Ragnarök: the end of the world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given Kratos’ past form, this connection is important to the plot of God of War.

Ragnarök’s relevance to the events of God of War is first revealed through an encounter with the Witch of the Wood: the outcast Freya. In Norse mythology, Freya is a distinct goddess, but in this game, she has been made a composite character with Frigg, Oðinn’s wife. Freya mentions to Kratos that there are very few living people left in the realms, as many have fled out of fear. She remarks that an unknown shift in the balance of the world has created the swarms of dead-like and maleficent beings in the realms.

Freya’s comment about the rise of dead suggests that Kratos’ actions in Greece in the first three games also had an impact in Scandinavia. She remarks that the gods of this realm know who he is and what he is capable of. While she does not explicitly divulge her knowledge of Ragnarök to Kratos, there are a few hints that she knows more than she lets on.

Subtle clues about impending events of Ragnarök appear throughout the 2018 game, and even one of its predecessors. At the very end of God of War III, during the final battle with Zeus, the seas begin to flood the earth and the sky turns black and fills with lightning. These phenomena are recorded in the medieval sources as precursors of Ragnarök. The Voluspa predicts “Sunshine becomes black the next summer.” Gylfaginning goes further, professing that “The sun shall be darkened, earth sinks in the sea.”

Like Father Like Son.

But if Kratos’s actions in Greece did affect Scandinavia, the question then becomes: how? In Norse mythology, Ragnarök stems from the actions of Loki and his children Jormungandr the world serpent, Fenrir the wolf, and Slepnir the horse. There is no mention of an angry, tattooed, Greek God.

The game resolves this issue by revealing in its finale that Kratos’s son, Atreus, is in fact Loki.

The reveal of Atreus’ identity at the end of the game is a bit of a bombshell. But there are a number of hints that this is the case throughout the game. Atreus has a deep connection with animals throughout the realms, specifically with Jormungandr (the World Serpent). This parallel’s Loki’s association with his animal offspring. Atreus carries mistletoe arrows, mirroring Loki’s association with the plant and Baldr’s death. Most tellingly, Loki’s mother was the giantess, Laufey–clearly represented in game by Atreus’ mother Fey.

The medieval narratives that record earlier Scandinavian lore, such as The Prose Edda, dispute the identity of Loki’s father. But in the game, Atreus/Loki’s father is a god (immortal) and his mother a giantess (a powerful but mortal being) making Atreus/Loki a demi-god. Because he is still immortal and of the realm of the gods, he can impact, relate to, or be a threat the other gods. But he can also be seen as an outcast, due to his quasi-foreignness and quasi-mortality.

Kratos is therefore the destroyer of not just the Greek, but also the Norse gods. Had he not destroyed the Greek gods and fled to the North, he would not have met Fey and begat Atreus/Loki. And without Loki, there is no true catalyst for Ragnarök. Kratos is truly the god of war, and no matter how much he tries to get away from it, he can’t avoid his nature and its ramifications on the world.

So, Who’s the ‘Good Guy’?

Considering all of this information, Kratos should be the ultimate evil, right? The game’s narrative structure is linear and follows a predetermined set of actions for the player as Kratos to perform. Regardless of how you, as the player, view the character of Kratos, you are obligated to follow the progression. There is no real opportunity to roleplay a “good” Kratos in the massive landscape.

As the narrative progresses, you learn that Kratos’s view of the world is sardonic and antagonistic, not exactly what you might expect for a heroic character. To hammer Kratos’ anti-heroism home, at one point he admonishes Atreus, saying, “There are no good guys, boy, I thought I taught you that.” Given the cold and vengeful outlook that he wears in the original trilogy, it would be strange if Kratos were to suddenly change. Though he is a parent, he has not changed his basic nature.

But having said this, Kratos doesn’t seem evil. The beauty of the game’s plot is the depth of Kratos and Atreus’s developing relationship and their heart-wrenchingly painful interactions, like when Kratos dejectedly carries his dying son back to Freya. With each challenge, Atreus becomes a bit more hardened, and Kratos becomes a bit softer. Kratos gets a bit more nuance with each step. This is actually in keeping the medieval mythological narratives.

Good Gods, Bad Gods

In the Old Norse myths, it can be difficult to tell the true intentions and morality of the characters. Unlike some other cultures or societies, which more-clearly define the moral characters of their supernatural beings, most Scandinavian gods and goddesses are not strictly good or bad. Certain characters may lean one way or the other, but most moral choices depend on the context of the moment.

For example, Oðinn has many names: The Helm-Bearer, The Changeable, The Concealer, Father of All, Attacker by Horse, Inciter to Strife, The Wise, Fiery-Eyed, and He who Lulls to Sleep, to name just a few.. He’s a formidable figure who disguises himself sometimes to test or trick people and other times to protect them.

Even the honorable ƿórr has a temper which leads to trouble when facing the Jötnar, the giants. One such example comes from The Poetic Edda:

Thor alone struck a blow there, swollen with rage, he seldom sits still when he hears such things said; the oaths broke apart, the words and the promises, all the solemn pledges which had passed between them.

Loki, a trickster, is sometime portrayed as a friend and companion of ƿórr, but other times as a mischievous child. In the instance of Ragnarök, he is one of the primary actors, but his actions are seen as inevitable and not merely a repercussion of his character traits to personal intentions.

These characterizations have led some scholars, like Jonas Wellendorf in his Gods and Humans in Medieval Scandinavia, to conclude that the medieval Scandinavians understood these figures as nearly human, with a blend of honorable qualities and fatal flaws. Perhaps this fickleness led to the types of ritual practices they developed. They sacrificed to remain in the favor of the powerful gods who influenced their lives. Gods were like people: they could be noble yet flawed or malicious with a kind streak.

It’s All Greek to Me

So, where does this leave us on God of War? Is Kratos a tragic hero with a disturbed past fighting to redeem himself? Or are the gods of medieval Scandinavia the “good guys” fighting to save their world from the threat of this foreign agent of destruction?

Perhaps it is a bit of both. It just depends on your perspective. Like many narratives of conflict, both sides in God of War and in Norse mythology truly believed in the justice of their cause. The Norse people depicted in the Christian and Islamic texts of the period are strange, tormented, malicious, and disgusting outsiders, and more notably, the evil despoilers of holy sites. You can find this characterization in Ahmad Ibn Fadlan’s account of a funeral from the 10th century, entitled “The Rus,” the monk Adam of Bremen’s hearsay account of a sacrifice at Uppsala, or the account from Lindisfarne in 793AD.

In the game, as in real life, the portrayals of villains and heroes depends on the author. Moral judgements are driven by the writer’s cultural background. The interactions in the game demonstrate this point very well; many of the beings that Kratos and Atreus meet along the way are cautious, threatened, or hostile to them. Freya spells it out to Kratos at one point: “The gods of this realm don’t take kindly to outsiders…”.

In the first three games, Kratos’ agenda is fueled by his lust for revenge. His morality appears lost in a sea of fiery confusion. His tortured soul is relieved when he releases “Hope” from Pandora’s box at the end of the trilogy and saves what little is left of Greece. But it is difficult to tell whether he did this for the sake of humanity, or to keep it out of the hands of the remaining Greek gods who had repeatedly betrayed him. For the majority of these games, Kratos was true to the title ‘God of War’ and plays the expected role of a callous ancient Greek god well.

In this new God of War, Kratos’ morality steadily evolves. He no longer kills everyone he meets. He cautiously considers his options before making decisions and tempers his anger, especially when it concerns Atreus. This dynamic provides room for Kratos to change. He becomes more like the Norse gods: morally grey with elements of nobility and of malice.

Ultimately, the game forges Kratos into a tragic hero. Since you see the world through his eyes, it reflects the way in which you are supposed to understand the other characters around you, and their culture as well. Kratos’ instinct for survival and wary opinion of others drives his antagonism to the gods of medieval Scandinavia. While attempting to redeem himself in this new landscape, Kratos cannot relinquish parts of his character or past. Maybe in a sequel he’ll become more than just the God of War.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.