Part XXXI in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Richard Utz. You can find the rest of the special series here.

In 1968, the Bishop of Regensburg, Rudolf Graber, made a momentous decision. He found himself in the position to shape the future of the College of Catholic Theology at the newly founded University of Regensburg, in southeastern Germany. As one of his decisions, he changed the plan to create a professorship in Judaic Studies; instead, he created one in Dogmatic Theology. The call to fill this professorship was accepted by a brilliant theologian from the University of Tübingen: Joseph Ratzinger. Ratzinger would then become first Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the successor to the Roman Inquisition, in 1982. And, of course, he would become Pope Benedict XVI in 2005. However, Graber’s decision to change the professorship’s focus from Judaic Studies to Dogmatic Theology may also have had another, less-well-known consequence.

One year after his strategic appointment of Ratzinger, an article in Der Spiegel exposed two things about Graber. First, that he had been a supporter of national socialist ideology and Hitler’s leadership.

But the paper also pilloried his outspoken support for something called the “Deggendorfer Gnad” (“Deggendorf Grace”).

The Deggendorfer Gnad was an anti-Jewish pilgrimage tradition in the small city of Deggendorf (in Lower Bavaria), which originated in the first half of the fourteenth century.

Specifically, Graber objected to calls for the removal of a cycle of early eighteenth-century paintings in the small city’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher that memorialized a long disproven narrative about how the pilgrimage came about—as an anti-Jewish “miracle”.

A Massacre, an Exoneration Myth, and Opportunism

The 1710 paintings (the above print versions of them were published in 1749) tell a lurid story. The story goes something like this:

In 1337, the Jews of Deggendorf enticed a Christian woman to steal hosts (the bread that represents the body of Christ) during Holy Communion. They, according to this story, attempted to desecrate these hosts by driving nails into them, by cutting them, hammering them, and burning them. To their surprise, each attempt apparently made a youthful Jesus appear—who then soared over the host. Discouraged, the Jews then apparently tried to cover up their crime by throwing the hosts in a well. The Virgin Mary then appeared miraculously to the citizens, exposing the crime, and the citizens burned the Jews in their anger. Subsequently, the citizens walked in procession from the well to their church to place the saved hosts in a beautiful monstrance, where they were forever preserved in immaculate condition. The narrative ends by depicting additional miracles, making a claim that a papal bull approved the sacred nature of the site, and recording the beginnings of a tradition of pilgrims coming to the site.

The actual historical record offers a very different version of events. Scholars, especially church historian Manfred Eder’s publications on the topic, demonstrate that, in 1338, the citizens of Deggendorf settled an economic crisis, which had been caused by a series of catastrophic harvests, by murdering the town’s Jews and stealing their property. The myth about a pre-1338 Jewish desecration of the host was clearly invented to exonerate, after the fact, the city’s Christian citizens. Some of them might have felt guilt about killing their Jewish neighbors, or they might have come under criticism by their neighbors. This was a wholesale rewriting of their history.

The massacre in Deggendorf was widely known. It spurred similar murders of Jewish people in more than a dozen other towns in the region. One of those places, according to the 15th-century Nuremberg Martyrologium, was Braunau, the birthplace of Adolf Hitler.

From Murderous Myth to Moneymaker

If the medieval mass-murder and property theft had “solved” a short-term economic problem for the Deggendorf citizens, the miracle myth, and the pilgrimages that it inspired, became a major source of recurring and reliable income for the town in the early modern and modern eras. Soon after 1338, sources began to claim that a host desecration had preceded, and thus justified, the citizens’ massacre of the Jews. By 1710, when the paintings were commissioned for the pilgrimage church, several conflicting local legends were consolidated and edited into one official narrative. In 1721, as many as 40,000 visitors are said to have traveled to Deggendorf; numerous religious rituals (processions, indulgences, litanies) and cultural practices (poems, plays, prose narratives, paintings) were created, and succeeded in (re)memorializing various aspects of the alleged host miracle over the subsequent several centuries. These practices successfully adapted to various new historical contexts. But the miracles surrounding the saved and miraculously preserved hosts (which have been proven to have been replaced with new ones several times when they showed visible decay) remained connected with their alleged cause: the desecration of the hosts by medieval Jews.

The Nazis, who were otherwise keen on suppressing Catholic pilgrimage traditions, permitted and even supported the Deggendorf pilgrimage because it easily connected with their own anti-Semitic agenda. In the 1980s, the priest of the Holy Sepulcher parish made a final attempt at revivifying the gradually waning tradition with a well-funded marketing campaign. But, when he removed the references to the false medieval accusations against the Jews, he found that the remaining (mostly conservative) supporters of the pilgrimage showed little enthusiasm for a ‘cleansed’ narrative. And so, finally, a full three decades after the Second Vatican Council—which officially condemned “hatred and persecutions of Jews, whether they arose in former or in our own days”—all official religious rituals and practices related to the pilgrimage were finally discontinued by the Bishop of Regensburg in 1992.

Projective Inversion

The genesis and reception of the Deggendorfer Gnad (numerous similar examples exist) show that there is an undeniable continuity between medieval and modern attitudes and actions toward members of the Jewish people in Europe. Fabricated, false accusations against Jews in the Middle Ages (of host desecrations, ritual murder, well-poisoning, usury, etc.), were a defining feature medieval Christian identity. Although accounts of anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism (for example, if you can read French, see Léon Poliakov’s Histoire de l’antisémitisme, 4 vols, 1955-1977; rev. edn. 1991) claim that all this changed with the onset of scientific modernity, there is ample evidence to suggest that this is not true. For medieval Christians as well as for post-medieval Christians (and non-Christians), Jewish otherness offered an opportunity to accuse the Jewish people of falling back into pre-Christian or pre-modern stages of civilization.

For example, from 1213 to 1215, the Catholic Church held a council of much of its entire leadership to decide many of the rules that remain part of Catholic orthodoxy today. One of these was the doctrine of transubstantiation, claiming that the bread and wine of communion literally become Christ’s flesh and blood during mass. However, after this, medieval Christians began to project their own fears about falling back into archaic forms of sacrificial anthropophagism—consuming Christ’s actual flesh and blood—onto the Jews, accusing them of ritual murder and desecration of the host. It is classic psychological projection: taking what you fear most about yourself and projecting it onto a scapegoat, which you can then hate and persecute freely.

Modern Christians continued to believe in the deceptively timeless nature of anti-Semitic myths with medieval origins because they were sustained by powerful narratives and rituals like the ones that sustained the Deggendorf Gnad. Their continued beliefs were then easily coopted and exploited by other individuals and groups in need of political scapegoats during times of increased insecurity and fear. In many of these cases, public health officials, butchers, and animal protectionists played a role. For example, numerous participants of the International Congress on the Protection of Animals in Vienna, in 1929, condemned the traditional Jewish slaughtering of animals in accordance with the Kosher laws (without stunning or anesthetizing the animal first) as a regression into premodern cruelty and unhygienic filth. These toxic views entered into easy alliances with Christian prejudice.

The politically motivated ritual murder accusations of Jewish people like Tisza Eszlár (in Hungary in 1883) and Mendel Beilis (in Kiev, Russia, in 1913) reveal exactly this kind of scapegoating of Jewish beliefs and practices. So do the opportunistic hate campaigns seen during the Third Reich, which featured ritual murder narratives in Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer. So too did the Hungarian nationalist “Jobbik” party’s anti-Semitic slogans, which claimed, as recently as 2008, that the Jews had “desecrated our [country’s] Holy Crown, [and] ridiculed the [medieval Catholic relic] Holy Right Hand.”

Complicity, and Resistance to Change

Had Bishop Graber appointed a chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Regensburg, the Deggendorfer Gnad would very probably have lost the official support of the Catholic Church as early as the 1960s. A chair in Judaic Studies, together with the strong movement to finally reform the Church’s medievalist teachings about the Jewish people—which was codified in the Second Vatican Council—would have led much earlier to the good scholarship on regional Jewish-Christian relations that emerged in the early 1990s. It was this scholarship that provided the overwhelming documentary evidence that exonerated the Jews and forced the hands of the religious authorities.

With hindsight, Graber’s decision now seems to be an active attempt by him at slowing down, or even thwarting entirely, the Council’s far-reaching decision to accept responsibility for the Church’s role in the suffering and eventual destruction of the European Jewry that began in medieval times and helped enable the Holocaust during the Third Reich.

Graber’s own national-socialist sympathies provide a plausible explanation for his anti-Jewish thoughts and actions. But his successors’ decision to keep the pilgrimage in place until after Graber’s death is different. It must be seen as another way in which far too many Catholic dignitaries have been resisting any criticism of the church, its practices, and its leaders, through the lens of history. History, after all, reveals traditions and rituals as grown, constructed, and time-bound. History thus challenges many religious beliefs, which claim a timeless bridge between, let’s say, Christ’s supper and every remembrance and reenactment of that supper.

We should remind ourselves that the stigmatization, demonization, and killing of Jews cannot be linked to any of Christ’s actions or views in the Biblical texts. It is the responsibility of those humans who claim to act in his name years and centuries later. Their actions, including the ones of church leaders, can and should be exposed for what they are, not cloaked as religious or cultural practices.

Deggendorf, Post-pilgrimage

If your travels lead you anywhere close to the region where Austria, Germany, and the Czech Republic meet, a visit to Deggendorf (situated along the Autobahn A3 between Regensburg and Passau) is a good investment. The city that has managed to transform its historical past—from the Middle Ages through the modern era—into a thoughtful learning experience. The Stadtmuseum Deggendorf, and its permanent exhibit on the Deggendorfer Gnad (opened in 1993), is a great way to see some of the texts and artwork that was created to celebrate and sustain the pilgrimage. The printed guide offered there was authored by Manfred Eder, a scholar whose doctoral dissertation provided the final incentive to discontinue the religious pilgrimage. Sadly, it is currently only available in print.

If your travels lead you anywhere close to the region where Austria, Germany, and the Czech Republic meet, a visit to Deggendorf (situated along the Autobahn A3 between Regensburg and Passau) is a good investment. The city that has managed to transform its historical past—from the Middle Ages through the modern era—into a thoughtful learning experience. The Stadtmuseum Deggendorf, and its permanent exhibit on the Deggendorfer Gnad (opened in 1993), is a great way to see some of the texts and artwork that was created to celebrate and sustain the pilgrimage. The printed guide offered there was authored by Manfred Eder, a scholar whose doctoral dissertation provided the final incentive to discontinue the religious pilgrimage. Sadly, it is currently only available in print.

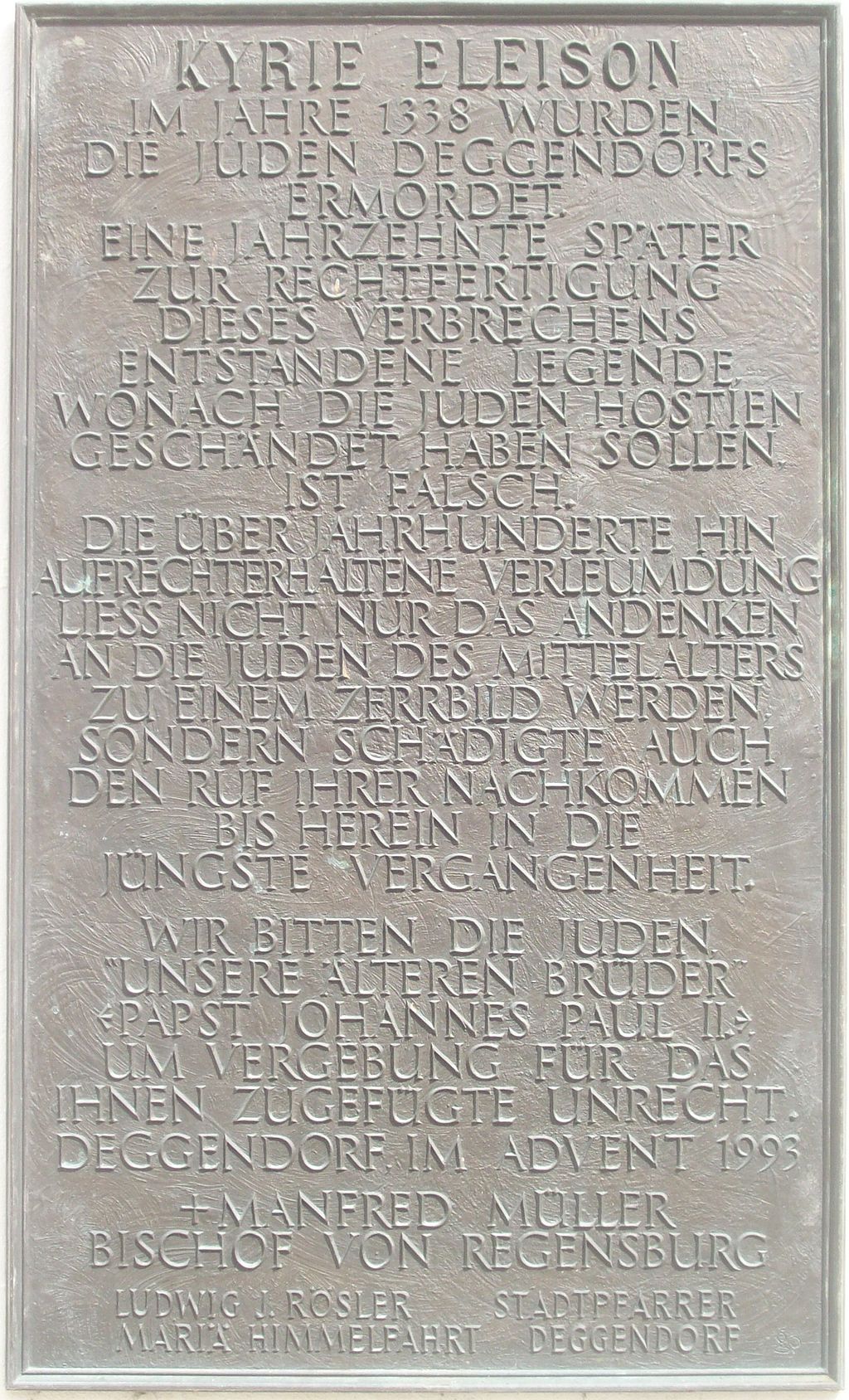

Another public sign of change is the plaque added to the outside of the Holy Sepulcher Church, seen above. It reads:

Lord have mercy.

In the year 1338 the Jews of Deggendorf were murdered. A decade later, to justify this crime, a legend was created in which the Jews desecrated the host, which is false.

Over the centuries, the slander continued to damage not only the memory of the Jews of the Middle Ages, but also to create a caricature that damaged the name of their descendants all the way into the recent past.

We ask the Jews, “our older bretheren” per Pope John Paul II, for forgiveness for the injustice done to them.

Deggendorf, in Advent 1993

It is only by publicly accepting the wrongs of the past, asking forgiveness, and making amends for them, that we may truly be able to surmount the injustices of our ancestors.

Coda: There and Back Again

Deggendorf has successfully engaged with its gruesome heritage. But the myth of Jewish host desecration has reared its ugly head again elsewhere. In the Bavarian diocese of Eichstätt, the “Heiligenblut” pilgrimage, also based on an alleged desecration of the host, made a comeback in 2005, when the diocese attempted to increase tourism to its places of worship. In its official communication on the reawakened event the diocesan leaders simply hush up the tradition’s troubling origins.

We must do better.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And click to subscribe here to recieve every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.

Thought-provoking, well-written and accessible, important essay. Excellent.