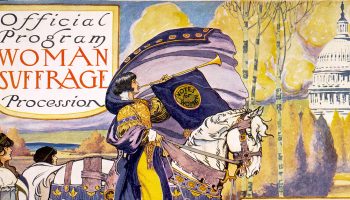

This is Part 5 of The Public Medievalist‘s special series: Gender, Sexism, and the Middle Ages, by Mariah Luther Cooper. You can find the rest of the series here.

Hillary Clinton’s run for the presidency inspired a record-breaking number of American women to run for office. And last Tuesday, they won. But outside the United States, this has highlighted the importance of gender in political arenas around the world. For example, a few years ago, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was asked why having a gender equal cabinet was a priority. He simply responded: “because it’s 2015.”

But why was that question necessary to ask at all? Why do people still debate women’s involvement in politics? Women are hardly new to the political arena. In fact, women have been participating in politics—even ruling over entire countries—since the Ancient World. This is true despite the highly male-dominated societies of their eras. And yet, there is a persistent myth that medieval women rarely participated in politics.

Women’s involvement in politics has been contested for centuries. In reality, medieval women were able to exercise real power, despite the fact that primogeniture (inheritance which favoured the eldest son) institutionalised the privileges granted to men in most places. And more, politically active noblewomen often had their accomplishments downplayed after their deaths. They were posthumously celebrated for their alleged conformity to so-called “appropriate” gender roles, rather than for their actual political prowess.

This domestication of women’s legacies via their death memorials accomplished two things. First, it worked to sustain images of what was considered “appropriate” feminine behaviour. And second, it undermined their actual authority and political achievements. This was often done at the request of the reigning male authority, whether it be their husbands, sons, or their political rivals. However, men were not the only participants in rewriting women’s legacies. Eleanor of Aquitaine, for example, notoriously belittled the post-mortem legacy of her husband’s mistress, Rosamond Clifford. She did this by commissioning Rosamond’s tomb inscription to read, in part, “…she who used to smell sweet, still smells—but not sweet.”

The managing of the memories of deceased women broadly permeated medieval society, as both noblemen and women participated in it. This process contributed largely to the enduring idea that medieval women were only wives and mothers and did not wield any true political power. But that idea is a myth.

Gender Expectations and Royal Women’s Tombs

The Empress Matilda of England (1102-1167 CE) was the proclaimed successor to the throne of her father, King Henry I. Her inheritance was accepted by the English nobility and clergy; she was to be the first ruling queen of England. But the crown was stolen from her by her cousin King Stephen, which led to a period of English civil war known as The Anarchy (which lasted from 1139–1153 CE). Matilda led a civil war, minted her own coins, produced charters, mobilized armies, and secured the throne for her son: the future King Henry II. But her political power was often ignored by both her contemporaries and by later historians.

The inscription on her epitaph praises the traditional accomplishments of Anglo-Norman aristocratic women, while minimizing her actual authority. Two lines from Matilda’s epitaph are now infamous in regards to her legacy; they read:

great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in offspring, here lies the daughter, wife and mother of Henry.

Matilda’s epitaph emphasizes her role as a daughter, wife, and, most of all, a mother, while ignoring her many triumphs as a powerful woman in a male-dominated society. This epitaph illustrates the larger trend in the Middle Ages of women’s memorials being manipulated in an effort to refashion their legacies to suit the needs of the reigning men.

Typically, the funeral monuments of royalty (including epitaphs, tombs, effigies, and memorial monuments) would emphasize the power of the deceased and their connection to the present monarch. Hence, royal tombs were made to illustrate that, despite the recently departed king or queen, the dynastic continuity of the line of succession would prevail. This was especially true for the tombs of medieval queens. Royal women were praised largely for their ability to maintain the dynastic line of succession through the birth of legitimate sons, regardless of their own political triumphs. Focusing on motherhood and connections to men greatly impacted the lasting feminine memories and legacies of these politically active women.

Eleanor of Castile (d. 1290 CE), queen of England and wife of King Edward I, is another woman whose burial erased her political legacy. Like Matilda, Eleanor wielded a great deal of political power. Eleanor engaged in both domestic and international affairs during the thirteenth century. Sarah Cockerill describes her as:

a highly dynamic, forceful personality whose interests in the arts, politics and religion were highly influential in her day—and whose temper had even bishops quaking in their shoes.

Eleanor manipulated policy and wielded substantial authority, despite “only” being the wife to the man in charge (Cockerill compares her to Hillary Clinton). In a historic letter written by Archbishop Pecham to Eleanor, he implicitly stated that she inspired her husband to impose strict justice of the law, as opposed to demonstrating appropriate womanly virtues of sympathy and pity.

During her life, Eleanor was condemned by her contemporaries as being a greedy foreigner. She was put in charge of acquiring land estates for the Crown, and she did this with great zeal. But one epitaph, written shortly after her death by the Archbishop of Canterbury, accused the queen of usury for inheriting Christian debts owed to Jewish financiers and, in turn, taking the indebted Christians’ lands. The queen’s perceived greed was also noted by her contemporaries; her household staff was notorious for carrying out acts of intimidation solely to meet her ends. For instance, when the church of Stockport had a vacancy, Eleanor requested one of her clerks to be the replacement. When Eleanor found out that her wishes were not fulfilled, she had her bailiff harass the lord of Stockport for seven years. This included confiscating his property and forcing him to pay fines.

Nonetheless, the enduring legacy of Eleanor is one of a virtuous, pious queen and good mother due to the careful construction of memory in her death monuments and memorialization. Edward I effectively commissioned an elaborate manipulation of her memory that minimized Eleanor’s unsympathetic traits—mainly her powerful landholdings, extravagant wealth and her fierce personality—and instead created an idealized version of her domestic virtues.

Her memorials demonstrate the development of royal female burials and how the way women were remembered was manipulated into a more sympathetic memory. For example, Eleanor’s effigy at Westminster Abbey is not meant to be a life-like resemblance of her. Instead, it is an idealized portrait that bears a striking resemblance to artistic portrayals of the Virgin Mary. The Virgin Mary was considered to be an excellent model of queenship, despite the unobtainable ideals she represented.

Often royal women praised the Virgin Mary as the true queen mother, and they admired her as the pinnacle of queenship. Her virtues of intersession, piety, mercy, and motherhood lent themselves easily to those of medieval queens. The Virgin Mary was understood to have received her majesty from her son, and by emulating the Virgin, queens could hope for greater power and influence by giving birth to healthy sons. Therefore, references to the Virgin Mary, as the mother of the king of kings, were frequently used on medieval queens’ funeral monuments. These references reinforced a queen’s piety and maternal successes, while also bringing recognition to the greatness of the reigning king.

Eleanor’s tombs also demonstrate the extravagance of royal women’s burials, which was meant to promote a greater image of the king and the monarchy. The numerous monuments dedicated to her, which include three tombs and twelve large crosses, were part of an elaborate attempt to manipulate her legacy. As was a common practice for the nobility in the Middle Ages, Eleanor’s body was separated into pieces after her death. She is buried in three places; her intestines are buried in Lincoln Cathedral, her heart at the Blackfriars of London, and the rest of her body in Westminster Abbey. The twelve crosses, erected at each place her body rested during the procession from Lincoln to London, were commissioned by her husband King Edward I. The inscription on Eleanor’s only surviving tomb at Westminster Abbey reads much like Matilda’s epitaph, in that it memorializes her role as a daughter and a wife. The inscription reads, in part:

Here lies Eleanor, sometime Queen of England, wife of King Edward son of King Henry, and daughter of the King of Spain…

However, unlike Matilda, Eleanor’s tomb inscription does not mention her sons or her role as a mother (which Eleanor was, sixteen times over). The emphasis on queens as mothers was common, so Edward’s neglect of this is striking. Yet, Eleanor’s memorialization as the good wife, and not the powerful landholding queen who aided her husband in counsel, was typical.

Eleanor’s and Matilda’s death monuments are similar in that they do not reflect true representations of these women, but rather serve the greater needs of the reigning kings. This demonstrates that medieval burial practices of royal women were part of a larger scheme that enhanced the reputation of the living royal men. Female domesticity was literally being written in stone via their death monuments; it continues to overshadow the actual power that these royal women were able to wield. Is it any wonder that many of us forget that women in the past possessed real political authority?

Rewriting Women’s Legacies Today

Women’s involvement in politics has been, and continues to be, a point of contention, despite the fact that women have been actively involved in politics for centuries. The way politically active women were memorialized during the Middle Ages can help to explain why the idea of modern women in politics is still so baffling to many. As John Parsons puts it, a royal woman’s tomb was used as “a blank canvas on which an ‘official image’ could inscribe accepted gender-power relations” of the time. The constructed memory of royal women, by way of their tombs and funerals, emphasised the socially acceptable roles of royal women as submissive wives and fertile mothers despite their actual political involvement and accomplishments. This presented culturally acceptable domestic legacies of powerful women, and to some degree, this sentiment still resonates today.

More recently, the former First Lady Nancy Reagan provides us with one of many potential examples of modern manipulation of politically active women’s legacies. With her recent passing in 2016, The Washington Post described her post-mortem legacy:

… [she was] more than a partner, a spouse and a steadfast caregiver to her husband…[in] the aftermath of her death…friends and former colleagues spoke of a legacy that is all her own: one of grace, kindness and loyalty to those she loved. They said she made her husband better and, with that, she made the country better.

Was the former First Lady just a good wife? During her lifetime, Mrs. Reagan was actively involved in the anti-drug “Just Say No” campaign, with which she went on talk-shows, visited drug rehabilitation centers, organized rallies at the White House and spoke at the United Nations. The lasting implications of the Reagans’ war on drugs is highly contested to this day. Nonetheless, with the passing of Mrs. Reagan, her legacy was enshrined as a loving and gracious wife, who took care of her ailing husband. Her political legacy, whether it be admired or condemned, is eclipsed by her more sympathetic virtues of being the good wife.

The public reaction to women in politics today, such as Margaret Thatcher’s cold-hearted moniker “the iron lady,” as well as the sheer novelty of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, is embedded in cultural power-dynamics. The media routinely perpetuates these gendered power-dynamics, as women’s histories are being rewritten, sometimes even during their lifetimes (Meghan Markel’s “rags to riches” narrative comes quickly to mind). However, similar to the past when the reigning male authorities would write noblewomen’s epitaphs, the media too is largely male-dominated. Forbes listed fifteen billionaires controlling the American news media, all of whom are men.

Thus, both during modern times and in the Middle Ages, how women’s legacies are being written is just as important as what is being written. The language used to describe powerful women in the Middle Ages, recorded in texts that were predominately written by men, is also reflective of societal expectations of an ideally domesticated queen. This, in turn, highlights societal anxieties, throughout history, towards politically powerful women. Fortunately, the domesticated memorials of medieval queens did not prevent their actual involvement in the politics of their time. Similarly, the sexist comments of the current media will not stop women’s involvement in current politics. Women in the Middle Ages did not succumb to the legacy of domestication and avoid involvement in politics, but instead continued to exercise strength and resilience, much like women are doing today.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.