Recently, I took a brutal, ten-hour transatlantic red-eye flight. And I was disappointed, though not entirely surprised, that of the three films I chose in order to pass the time (The Big Lebowski, The Dark Knight and The Muppets), none of them passed the Bechdel Test.

For those of you unfamiliar with it, the Bechdel test is a basic gauge of female representation in films. The rules of the test are pretty simple. In order to pass, any given film must have:

- Two named female characters

- Who talk to each other

- About something other than a man.

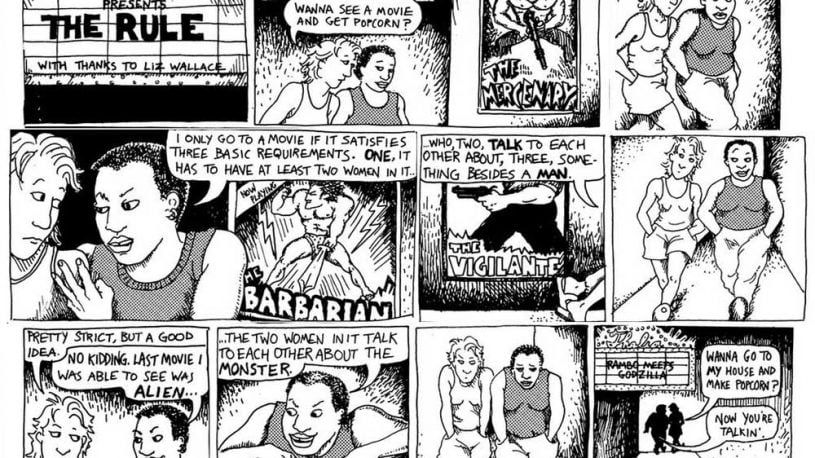

There are a few variants to the test. But that the above three rules constitute its most basic form, as invented by Alison Bechdel, creator of the comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For“. Here is the strip in which she invented the test [click to enlarge]:

The test in this form intentionally sets the bar for female involvement in films ridiculously low. And yet, it was pretty shocking (or sadly perhaps not shocking at all), how when people first started examining films this way, few passed.

Of course that’s not to say that passing makes a film better, or that every film should pass. But as a very basic tool of meta-analysis of representation of women in film, it was useful in simply revealing industry-wide bias in scripting and film-making that so few films could cross even this lowest of bars when it came to the basic representation of women.

As a scholar of the representation of the Middle Ages in popular culture, I began to wonder how many medieval films actually pass the Bechdel test. My working hypothesis was that it would not be many. And sadly, that hypothesis has bore fruit:

| A Knight’s Tale (2001) | Fail |

| Beowulf (2007) | Pass |

| Brave (2012) | Pass |

| Braveheart (1995) | Fail |

| Excalibur (1981) | Fail |

| First Knight (1995) | Fail |

| Henry V (all versions) | Pass |

| King Arthur (2004) | Fail |

| Kingdom of Heaven (2005) | Fail |

| Monty Python and the Quest for the Holy Grail (1975) | Fail |

| Robin Hood (2010) | Pass |

| The 13th Warrior (2011) | Fail |

| The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) | Fail |

| The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003) | Fail |

| The Name of the Rose (1986) | Fail |

| The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) | Fail |

| The Seventh Seal (1957) | Fail |

[Note: This list is far from complete, and compiled from my own collection and http://bechdeltest.com/. If you have a correction or more films to add, tell me in the comments and I’ll add it to the table]

I imagine this little list is no great surprise to anyone. A significant strand of medieval films focus on heroic warrior-adventurers and their military campaigns. The epic film genre demands a love interest for our hero, but other women are, within that paradigm, extraneous. And certain other specific examples are perhaps understandable: The Name of the Rose oughtn’t necessarily have female significant characters. It’s arguable that so many Bechdel failures within the corpus may be a natural byproduct of the type of stories told in film. That having been said, that is a problem. Sure, we can excuse The Name of the Rose, but A Knight’s Tale? Excalibur? Joan of Arc? And yes, The Name of the Rose should be excused, but where are our depictions of medieval nuns and abbesses?

It’s arguable that a lack of female presence in medieval films is also a byproduct of the very Middle Ages from which they are drawn. Men dominated medieval oral, and later written, culture, especially due to written culture largely being the purview of male monastics for the early part of the period. There are some wonderful exceptions, like Marie de France, Margery Kemp and Christine de Pizan. But even in my reading of the lais of Marie, I don’t know any of her tales that would pass the Bechdel test. I have not read every medieval romance (nor am I sure it’s possible to), but I do wonder how many, if any, would pass. [If you know of some, do share in the comments below].

I don’t write this as a matter of idle curiosity. In my research on people’s perceptions of the Middle Ages and how they’re shaped by films, time and again I found people–even women— downplaying or even disregarding entirely the role of women in the medieval world. And thus they saw women’s exclusion from films about the period justifiable, normal, even occasionally desirable.

This is a problem.

Now, I would never argue that women were not socially oppressed in the Middle Ages, and as a result underrepresented in medieval narratives of all kinds. But it is this exclusion which make their stories so worth recovering, taking seriously, and depicting today. Otherwise this denigration of the contribution of over half the population will be perpetuated and re-perpetuated over the generations until it seems normal for women’s lives to be excluded from a thousand years of history.

The question is, where to start? Obviously what I am suggesting is more than just adding a token plucky friend-of-the-love-interest to the next epic, or making medieval rehashes of Xena Warrior Princess. But there are a huge range of perfectly cinematic women’s stories from the Middle Ages. I am continually baffled why we have yet to see a biopic of Eleanor of Aquitaine; instead she plays second fiddle in A Lion in Winter and third fiddle in Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood. I’d love to see a Hollywood take on Christine de Pizan’s City of Ladies books. Or The Book of Margery Kempe. Or, if nothing else, give us more interesting stories of fictional medieval women, outside the standard love-interest/evil-queen dichotomy.

The good news is, a sea change may be coming.

There has been an increasing recognition that better representation of women in cinema is not only good in an abstract sense, but result in better profits. For example, statistician Walt Hickey, writing for FiveThirtyEight.com, recently ran a meta-analysis of the Bechdel test against box office profits in his article: “The Dollar and Cents Case Against Hollywood’s Exclusion of Women“. Hickey found, among other things, that films which pass the test outperform those that do not. Hollywood is nothing if not concerned with its bottom line, and hopefully this change will ultimately result in more representation of women in medieval films as well.

And similarly, despite its intense focus on titillation, Game of Thrones has more, and more varied and interesting female characters than I have ever seen in a fictional version of the Middle Ages. While it is certainly assailable from a feminist perspective for objectifying women (so much so that it has coined the term ‘sexposition’), it does eschew some of the old clichés where women are only relegated to evil queens and passive love interests. Catelyn, Cersei, Margaery, Sansa, Arya, Brienne, Daenerys, Shae and more; these are complex women with rich, compelling stories to tell. And while Game of Thrones is not strictly medieval, it is recognizably so—as are the stories of its women.

Since Game of Thrones is the most popular show on television at the moment it is sure to spawn imitators. We can only hope that they learn the right lessons from it.

In short, give us more medieval women, Hollywood. Ideally ones that you don’t force to take their clothes off to get the viewers’ attention. When it comes to passing something as simple as the Bechdel test, it should be more surprising when a historical story doesn’t pass than when it does.

The third requirement is a bit rough given the middle ages. For instance, two women having a discussion about religion or politics could be categorized as “talking about a man” (Jesus or the king). I think Matilda and Eleanor of Aquitaine speak to one another in Becket, but it’s undoubtedly “about a man” — the poor qualities of king or archbishop. Plus there are non-“man” topics that are ridiculous and sexist, like female characters only discussing fashion or makeovers. Outside that caveat, though, good points and something I will watch for.

It’s not a medieval romance (it’s an early modern one), but I’m pretty sure Floridoro by Moderate Fonte passes the Bechdel test. It’s the only example I know of.

That’s a really interesting one; I’ll have to give it a read, thanks! But yes, I still haven’t been able to find any medieval ones. A bit sad that there are so few– if any!

Reverse Bechdel’s test:

1. The movie features 2 named male characters…

2. Who talk to one another…

3. About something that is not plot related.

The problem with B.T. is that the overwhelming female life-success strategy throughout the ages was “Find a man who can provide for you and marry him”. That was, and for many still is, their objective.

From men, societies demand solving problems – from “small” problems, like “How will you earn money”, to big problems, like “How will you stop the huge army marching against your land”. And pretty much every man was required to participate in this problem solving.

So you get huge amount of movies with named male characters who engage in conversations – but those conversations tend to be plot-oriented. Even seemingly “small-talk’ish” talks, like when the dwarves in The Hobbit, on the first night, tell Bilbo about the fate of Thorin’s grandfather, later turn out to be plot-related. Essentially, movies depict men as these soldiers on a war path – soldiers who have to defeat the enemy, or save the princess.

And of course, there’s the question no-one seems to want to ask: “If women don’t like the movies being produced, or, rather, if they see some serious flaw with them, why don’t they make better movies?

Why are they asking “the evil men” to make movies for/about women?

Where is the feminist take on Joan of Arc? Where is a movie about Boadicea? About Cleopatra?