Part XXV in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Matthew Chalmers. You can find the rest of the special series here.

“It’s anti-Judaism!” they barked. “There is no “anti-Semitism” until 1879.” The seminar at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies in Philadelphia had taken a gladiatorial turn. The cause? A terminological concern—something fairly common among Jewish Studies specialists. The critic’s objection? An offhand reference by the speaker to “anti-Semitism” in the sixteenth century.

True enough, prior to its emergence in late nineteenth-century Germany, no term with the root “Antisemit-” existed in common use (this is a complicated topic, so for more see chapter 2 of the book Rethinking European Jewish History). Even the term “semites” only emerges in the eighteenth century. “Semites” were defined (according to the best linguistic science of the time) by grouping together those who spoke languages such as Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic—as opposed to those languages called “Indo-European” (or sometimes, even more problematically, those with cultures designated as “Aryan”).

Many therefore argue that talking about “anti-Semitism” in the Middle Ages is anachronistic. So, what is it doing in a series dealing with medieval Jews and Jewishness? How helpful is it to talk of “anti-Semitism” before, as far as we know, anyone discriminated against Jews as semites—or even knew what a “semite” was? And how can thinking about that question let us think more deeply about the larger issues this series has concerned itself with—that is, race, racism, and the Middle Ages?

“There’s No ‘anti-Semitism’ Before 1879”

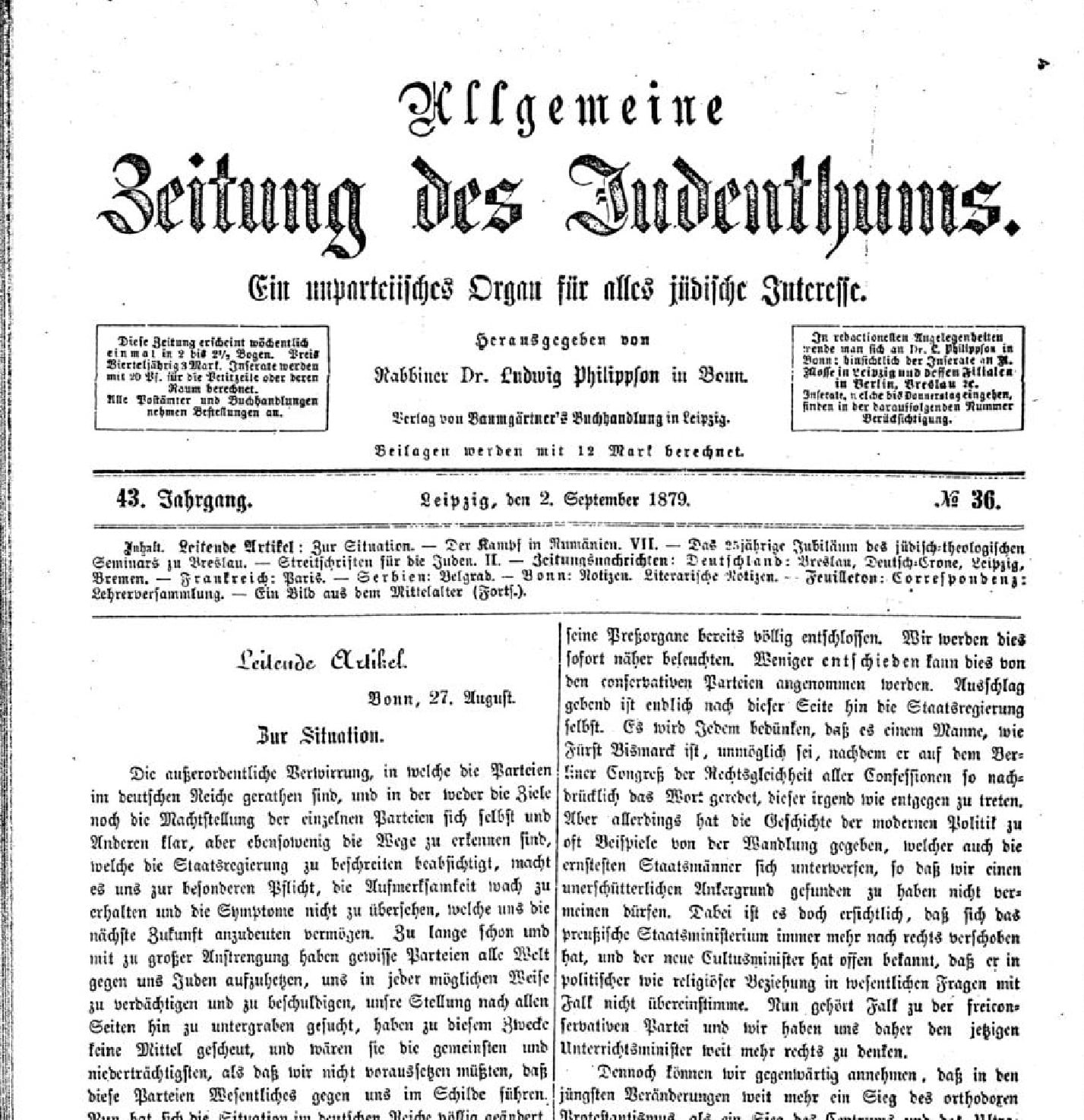

There are two main schools of thought about the term “anti-Semitism.” Those in the first camp tie “anti-Semitism” to its linguistic occurrences—namely, when ordinary people used the words. They (correctly) note that the neologism “anti-Semitism” emerges onto the German literary scene around the 1870s and 1880s. To my knowledge, the first recorded use is in the Jewish newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums (2 Sep. 1879, p.564), which deployed it to criticize friends of a certain Wilhelm Marr, who planned to produce an “anti-Semitic weekly.”

Some, moreover, argue that while anti-Judaism has a long history, it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that racism—and hence “anti-Semitism”—became a primary principle of social organization. This, they suggest, was catalysed by internal European nationalism and the so-called scramble for Africa. For example, historian David Engel writes:

…no necessary relation among particular instances of violence, hostile depiction, agitation, discrimination, and private unfriendly feeling can be assumed. Indeed, none has ever been demonstrated. Historians who, by treating some or all instances as part of a general ‘history of antisemitism’ and theorizing about how the subject of that ostensible history should be defined, have nevertheless made such an assumption have done so on the basis not of empirical observation but of a socio-semantic convention created in the nineteenth century and sustained throughout the twentieth for communal and political ends, not scholarly ones.

In other words, as Engel argues, mashing together instances of anti-Jewish behaviour into “anti-Semitism” is misleading. It fails to reflect the situation on the ground in terms that those involved would have recognized. Thus, it forces often very different events into an artificially connected series, which inflates—and maybe even distorts—the significance of such events. The category of “anti-Semitism” ends up driving the history, not the other way around.

These scholars also suggest that it makes little sense to import a chronologically foreign term, “Semitic,” into any time or space in which its partner term, “Aryan,” was not used. This pair resonated in a specific political context. “Anti-Semitism” as a term became meaningful in debates about the assimilation and emancipation of Jewish communities throughout the developing democracies of nineteenth-century European nations—especially Germany. How, therefore, could the word have comparable meaning prior to those political and social settings which give it its documented, traceable historical content?

From anti-Judaism to “anti-Semitism” in the Middle Ages

Other scholars, in the second camp, trace the origins of anti-Semitic behaviour to the Middle Ages. Some scholars even trace the origins of anti-Semitism back to ancient Greece and Rome. That said, in general, specialists have been wary to extrapolate “Jewish” as a stable religious identity back before the collation and editing of rabbinic literature; the Mishnah (c.200CE) and the Talmud (c.600CE). After all, many of the characteristic practices of Jews that their opponents targeted (such as synagogue liturgy, festival observance, and halakha) rely on this literature and its interpretation.

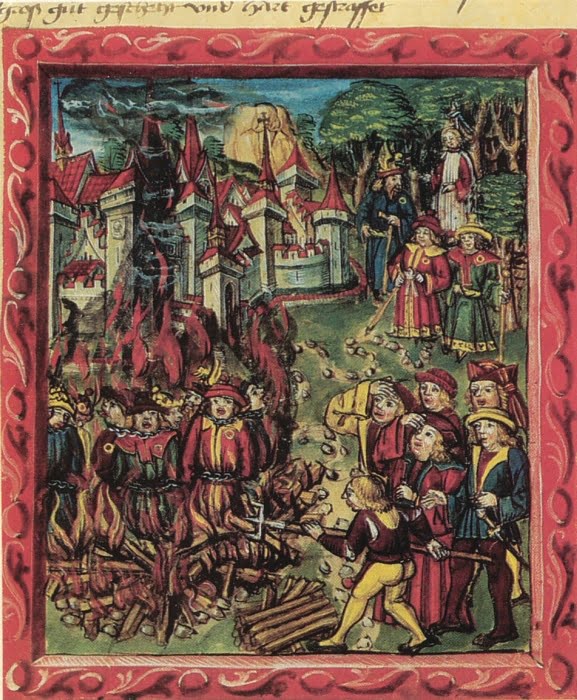

Many scholars therefore follow a timeline similar to the one laid out in the 1960s and 1970s by historian Leon Poliakov in his monumental four-volume History of Anti-Semitism and explored by historian of Judaism Gavin Langmuir over the course of his thirty year career. This timeline argues that “anti-Semitism” kicked into high gear in the twelfth century, riding the wave of anti-Jewish violence in the wake of the First Crusade (1095-99). The medieval transformation of anti-Jewish imagery into a “staple” of European thinking vis-à-vis Jews then, as Professor Robert Chazan has talked about at length, results in modern “anti-Semitism.”

This transformation goes hand in hand with various arguments that the eleventh to thirteenth centuries saw the emergence of what R.I. Moore called a “persecuting society.” That “persecuting society” organized itself by grouping together those perceived as deviant (heretics, Jews, lepers) under a shared set of idioms for exclusion. It also more and more consistently portrayed the demonic in feminine form. It increasingly contrasted its own Christian identity to an imagined enemy of Christendom that sometimes took the form of a Jew and sometimes that of a Muslim.

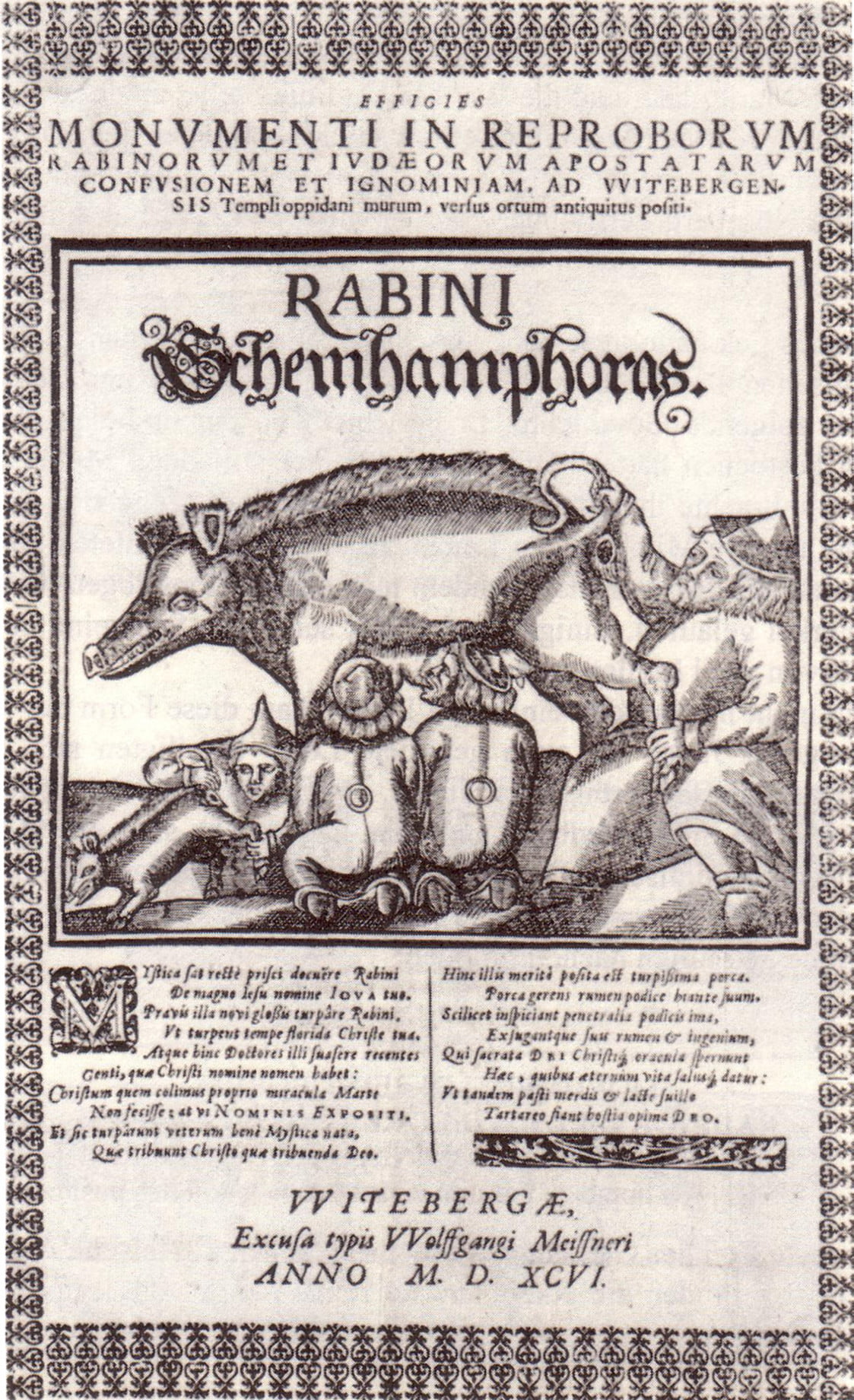

By the convergence of these factors, Jews came to feature heavily in European Christian imaginings, both about contemporary Christendom and its future decline and fall. One of the most fascinating stories which the period produced is that of the ferocious Jewish lost tribes, becoming in Germany the “red Jews.” This race of monstrous destroyers would, it was feared, burst from behind the mountains of the far east and crash down onto Christian Europe. The Book of John Mandeville from the middle of the fourteenth century provides the Sparknotes version:

Men say that they will issue forth in the time of Antichrist, and that they will carry out great slaughter of Christian people. And for this reason, all the Jews that dwell in all lands always learn to speak Hebrew, in the hope that, when those of the Caspian mountains issue forth, the other Jews will know how to speak with them, and will conduct them into Christian lands, to destroy Christian people.

Such a story departed from the Christian scriptures and from the history of scholastic exegesis, the interpretation of the Bible as taught in universities like Paris, Bologna, or Oxford. Rather, it constituted a durable “extra-Biblical system,” combining three sets of old stories into a fresh anti-Jewish cocktail. First, old stories around Alexander the Great, in the traditions of the Alexander Romance, told of how the conqueror had imprisoned monstrous races behind a massive mountain chain in the east. This then merged with legends of the ten tribes of Israel lost after the conquest of the northern Kingdom by the Assyrians in 722BCE. Third, the biblical motif of Gog and Magog, the destroyers at the end of time, was added to the mix, tinged with viciously anti-Jewish rumors about ritual murder and child sacrifice.

Faced with such a sophisticated set of interlocking hostile attitudes and consequent pogroms, scholars from this camp have argued that such narratives are symptoms of a systemic fear of Jewishness: monstrous bodies, social threat, wielded as a weapon against the European Christian. This looks rather like an equation of blood, body, ethnicity, and religion. Doesn’t it thus make sense to include such systematic prejudice along with the “anti-Semitism” of later periods?

Medieval “anti-Semitism”: A Useful Tool?

The key point turns, in part, on whether “anti-Semitism” is more appropriately thought of as a linguistic term—as the first academic camp holds—or a concept—as the second does. This academic debate is ongoing; there’s no chance of us resolving it here. Instead, steering away from the debate for a moment, what are the stakes of approaching pre-modern Jews with “anti-Semitism” in mind? Is it helpful to do so? What are the problems inherent in doing so?

On the one hand, there are some benefits to using “anti-Semitism” to refer to medieval anti-Judaism. Extending “anti-Semitism” back to the Middle Ages helps short-circuit arguments that modern anti-Semitism emerges without any causal or ideological precedent. It shows, in other words, anti-Semitism’s history.

Doing so also helps avoid overly rigid divisions between religious anti-Judaism and racial anti-Semitism. This type of division relies too much on separating the pre-modern from the modern, or the religious from the political, or the sociological from the psychological. People in the past, and the sources they left behind, do not chop these things up in the same way as we do—we should be careful in assuming they did. There was nothing inevitable about modern “anti-Semitism.” It resulted from specific, contingent ways of thinking, behaving, and fearing. And nor can it be bundled away as reliant on the religious past, or outdated racial thinking. It is a much more pervasive ideology; it conflates race and religion, and draws on both.

Moreover, “anti-Semitism” is admittedly an anachronistic term. But deploying tactical anachronism, as professor of Medieval Literature Kathy Lavezzo points out, can help us understand what type of ideas we are dealing with. In this case, it helps signal that the history of Jews (and their identities) relies in equal measure on historical sources, their present-day relevance, and our own habits of language and conceptualization. In other words, it isn’t just about what really happened. Our histories of Jewishness work best when they account for the effects of Christian anti-Judaism If they don’t, then they underestimate the effects of the past on our present ways of thinking about history.

Paying attention to this is particularly important when it comes to Jewishness. As Jewish Studies scholar Cynthia Baker has recently argued in her book Jew, to talk more generally about identity in America or Europe uses a vocabulary of difference reliant on past interactions with Jewishness. Professor of Religious Studies Annette Yoshiko Reed teases out the ramifications in a recent Marginalia forum addressing Baker’s book:

Jewishness functions for Christianness perhaps akin to what Frank B. Wilderson III notes of blackness with respect to “the racial labor that Whiteness depends on for its unracialized ‘normality’”: it is the particularity without which a claim to universality cannot be articulated.

In other words, whiteness—and white supremacy—can behave as it does because it has learned to point away from itself, and instead point at black people as particular, different, as things worth pointing at. Without this act, whiteness could not function as a universal default; it might come to be seen itself as a thing worth pointing at.

In the same way, Reed suggests, it matters that Christians could point at Jews. Without that act of pointing, Christianity might never have become capable of being the assumed default position of many Europeans and Americans. This all implies that past interactions with Jewishness lurk semi-submerged under many of our assumptions about the European Christian past—and our own identities in the present.

So, the question is not just whether such concepts and the terms relating to them are accurate. The issue at stake runs deeper than utility. Rather, how and to what degree, if used carelessly, do terms like “anti-Semitism,” “Jewishness” or “whiteness” have the power to quietly rewrite our histories? How much can these words veil, rather than reveal, the details? And how much do we care?

Drawing attention to the negative treatment of Jews in European history using a term that jars us, that stands out as anachronistic (i.e. “anti-Semitism”), rather than a more general term (i.e. “anti-Judaism”) can, perhaps, help train us to continually question which words we use, and consider how anachronistic they may or may not be. Such attention also helps us take a long hard look at what, therefore, we want to get out of the past.

Medieval “anti-Semitism”: Obscuring the Past?

On the other hand, interpreting all anti-Jewish activities as signs of “anti-Semitism” has its dangers. We have developed a robust rule-of-thumb for what “anti-Semitism” means: discrimination against Jews as a whole group. But stretching this “anti-Semitism” back into the Middle Ages risks implying that the story of those later classified as “semites” is a story only about Jews. This spurs us on to scrutinize the darker parts of the European Christian past—not a bad thing in itself. But narrowing our view leaves out another piece of the puzzle: it threatens to obscure Islam from discussion, when European Christian identity formation cannot be understood without examining the ways that both Jews and Muslims were treated and imagined. As Edward Said writes, Arab and Jew were inseparable in constructing the category of “semitic”:

the transference of a popular anti-Semitic animus from a Jewish to an Arab target was made smoothly, since the figure was essentially the same.

Often, as Dorothy Kim (and others) argue, Muslims were even fundamentally connected with Jews in fraught relationships with medieval Christians. In his Dialogue of Peter and Moses, the twelfth-century Jewish convert Petrus Alphonsi inserted a heretical Jew into the backstory of the prophet Muhammad. The dress code “recommendations” in Canon 68 of the Fourth Lateran Council (another large church council, this time in 1215) targeted both Jews and Saracens. It notes that they could blend and become, to Christians, threateningly indistinguishable both from one another and from Christians themselves—even mistakenly resulting in prohibited sex:

In some provinces a difference in dress distinguishes the Jews or Saracens from the Christians, but in certain others such a confusion has grown up that they cannot be distinguished by any difference. Thus it happens at times that through error Christians have relations with the women of Jews or Saracens, and Jews and Saracens with Christian women. Therefore, that they may not, under pretext of error of this sort, excuse themselves in the future for the excesses of such prohibited intercourse, we decree that such Jews and Saracens of both sexes in every Christian province and at all times shall be marked off in the eyes of the public from other peoples through the character of their dress.

Furthermore, detaching “anti-Semitism” from its modern race-scientific core and its specific Euro-American history risks reintroducing an “eternal Jewish victim,” a character that slips out of our historical control. Anti-Semitic ideology often relies—like other modes of racial thought—on a hyper-realized Jew, whose characteristics are frozen in time. By losing the modern core of the ideology, we risk letting Jews become a stable constant around which history changes, and thus permitting this ideology in the back door.

In a review essay of three recent monographs on early modern Jewishness and race, scholar of religion Gil Anidjar makes a similar point. By stretching race—and racial “anti-Semitism”—back in time:

…the seat of progress, the center of this newfound and militant search for racism everywhere, is thereby washed clean of one of its most striking specificities: “the formation of a scientifically buttressed system of racial hierarchy,” the invention of a juridical and scientific mode of government which by way of military and bureaucratic (and scholarly) measures, transformed the populations of the world into mere instances of a narrow series of political categories: race or religion, caste or class, culture or gender.

Anidjar here reminds us that racism and thus “anti-Semitism” have their own concrete historical past. “Anti-Semitism” depended for its meaning on specific scientific and academic developments. Stripping away that concrete history implies that there is something about Jews in and of themselves, in any place and at any time, that solicits hatred. It freezes a fixed object, Judaism, as if what is important about Judaism when discussing “anti-Semitism” is that Christians victimize Jews—rather than giving any complex agency to Jews in history—and as if Judaism has been the same type of thing for over a thousand years. As Albert Lindemann writes, this can turn the Jew into a universalizable moral fable, turning both Jews and their antagonists into one-dimensional moral tales resistant to the more cautious tools of the historian—and even erasing any specific reference to their Jewishness:

Violent episodes against Jews burst forth like natural calamities or acts of God, incomprehensible disasters, having nothing to do with Jewish actions or developments within the Jewish world but only with the corrupt characters or societies of the enemies of the Jews. Even Jewish victims themselves in these accounts are implicitly denied their full humanity and often appear one-dimensional, passive and blameless, or heroic in a way that lacks a sense of human frailty and corruptibility under stress. Rather than tragedies, with often confused, inscrutable mixtures of motivations, conflicts between Jew and non-Jew emerge as simple stories of good and evil, innocence and guilt, powerless and powerful, heroes and villains.

To Think with “anti-Semitism”—or Not

On the other hand, thinking about the Middle Ages through the lens of “anti-Semitism” can be a good thing. Scrutinizing how the term “anti-Semitic” strays back in time similarly provides an opportunity to light up a different path through the mazes of the past. By making the process of concept-formation visible, we see more clearly what affects our own assumptions—and the behaviours helpful to us in making sure we write our histories, rather than letting our inherited assumptions speak for us. And it acts as an easily recognizable shorthand, a hook on which our thoughts can wriggle around.

In short, whether we want to use “anti-Semitism” or not, thinking about what is at stake in our choices can concentrate our attention on what we want to get out of the past. We—all of us spending time with the past, not just professional historians—remind ourselves of a somewhat awkward fact: our main historical challenges often come not from anachronism, which we are often rather good at spotting, but from taking for granted that we know exactly what’s at stake in the concepts and questions with which we approach history. Paying attention, instead, to how concepts like “anti-Semitism” distort or describe the past helps equip us to sensibly and sensitively negotiate our shared and contested pasts—especially on topics as fraught and urgent as “anti-Semitism” and race.

The Public Medievalist does not pay to promote these articles, so we would love it if you shared this with your history-loving friends! Click to share with your friends on Facebook, or on Twitter.