Part XLIII in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Ken Mondschein.

A working knowledge of medieval history once again offers insight into the national news. On February 12th, United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions pointed to sheriffs as “a critical part of the Anglo-American heritage of law enforcement” at the National Sheriffs’ Association annual conference.

This statement was incredibly fraught. While Sessions may have been technically correct, the fact that he added “Anglo-American heritage” to his speech as an improvised line, especially at a conference of sheriffs, was widely interpreted as being a racist dog whistle. Many saw the statement as implying the superiority or centrality of “Anglo-American (read: white) heritage” in the contemporary United States.

Given Sessions’ history of racist comments as well as of instituting policies which disproportionately negatively affect people of color, his critics were quick to call him out. For instance, in a statement, the NAACP said that Sessions’ comment is “an unfortunate yet consistent aspect of the language coming out of the Department of Justice under his tenure” and that it “qualifies as the latest example of dog whistle politics.”

Whether he realized it or not, Sessions’ statement had two references to medieval history buried deep within it: the idea of the power of sheriffs, and the idea of “Anglo-American” law. In this we can read Sessions’ words as a part of a disturbing pattern, where pieces of the medieval past are used to justify white supremacy.

“You’re not wrong…”

Sessions can use history as a fig leaf to suggest his intentions were innocent. But his words can easily be seen as another example of a “Schrödinger’s Medievalism,” that is, a symbol that can, depending on context, be interpreted in a racist or a benign way. In this case, unlike the case explored by Paul Sturtevant in his article, we don’t have a flag or other physical object. Instead, we have a common legal concept with medieval roots being used in a manner that suggests the superiority of white “Anglo-Saxon” culture.

Let’s look at the history behind the words. Though the word “sheriff” invokes a spur-clattering gunslinger from the Old West, historically, the sheriff was in charge of the ordering and defense of a shire. A “shire” is not just a locality in The Hobbit, but was actually one of the administrative divisions of Anglo-Saxon England and, after the conquest of 1066, of Norman England.

The word itself is a contraction of “shire reeve” (a reeve being a “guardian” or “protector”). Though the Angles and the Saxons conquered England in the fifth century ce, as W.A. Morris wrote in his 1916 article “The Office of Sheriff in the Anglo-Saxon Period,” the office of sheriff per se only seems to have come into existence in the mid-tenth century after King Æthelstan unified the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Later, the term “reeve” (such as the character of the reeve in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales) came to mean the managers of individual manors, while sheriffs remained in charge of administering royal justice. The office was later brought to the New World; the first sheriff in the English colonies was Virginia’s Captain William Stone, who was appointed in 1634. So, sheriffs are indisputably part of both medieval English history and, by extension, American law.

A recent Slate article by Daniel Horwitz explained why Sessions’ statements at a conference of Sheriffs is particularly bad. He writes:

To many people of color, who are still disproportionately targeted by local law enforcement today—even for minor crimes like jaywalking and marijuana possession—the disturbing history of institutional racism in the “historic office” of sheriff may resonate to this day.

To today’s white nationalists, however, Sessions’ full-throated embrace of “the Anglo-American heritage” of local sheriffs would mean something else entirely. For decades, far-right extremists have seized upon the mantle of “posse comitatus”—a legal doctrine providing for substantial deference and authority to county sheriffs—as a basis for rejecting the federal government’s authority to enforce civil rights laws. The notion that sheriffs reign supreme over federal law enforcement officers is also a central claim of self-styled “sovereign citizens”—right-wing anarchists who “recognize the local sheriff’s department as the only legitimate government official.”

Medieval history can offer even deeper roots to Horwitz’s analysis; sheriffs’ troubled relationship with civil rights also has roots in the medieval past.

For example, as elected officials, modern sheriffs are ultimately responsible to the voters. This is rooted in history: As J. R. Maddicott showed, by the thirteenth century, sheriffs were commonly selected from the notables of a shire, rather than the king, which placed their base of power closer to the people. As Richard Christopher Gorski wrote in his masterful PhD dissertation,

The fourteenth century therefore saw a gradual refinement of the qualifications that sheriffs and other officials were supposed to hold, and a consolidation of the gentry’s grip on local government.

In other words, medieval sheriffs had a vested interest in the status quo. This tradition was also carried over into the New World; William Stone, for instance, was a powerful landowner. While Stone was appointed, only twenty years later, in 1652, sheriffs began to be elected. Of course, considering, as the right to vote was limited only to white, male property-holders, early sheriffs tended to be men of property. This has meant that, over the years, some had a vested interest in both keeping the disenfranchised from voting, and in playing to the bigotry of the masses.

Since the Middle Ages, sheriffs also have had the right to summon the “posse comitatus”—which comes from medieval Latin for “power of the county.” A posse, for short, enabled a sheriff to conscript all available able-bodied, armed men to enforce the law. Posses are most often associated with the Old West, but they were not only used there. They were also responsible for numerous lynchings, such as the 1919 murder of 219 African-Americans in Arkansas.

Today, far-right activists have also seized on sheriffs as key to ensuring their particular idea of liberty. For instance, John Darash, a retired carpenter from New York and advocate of the “sovereign citizen” movement publishes material exhorting sheriffs to follow his ideas for disrupting the “unconstitutional” US government.

As in the Middle Ages, American sheriffs are also charged with executing warrants, ensuring public safety, and running local jails. But this authority often affords them considerable leeway, which has led to abuses like the infamous tent city jail run by Joe Arpaio of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office.

What about the idea of “Anglo-American law?” Like the office of sheriff, the United States’ legal system was modeled after the English system. “Anglo-American law,” thus, is actually a very common legal term. It is not typically racially charged. For instance, then-senator Barack Obama used the term “Anglo-American legal system” in a floor speech in 2006.

What makes these two systems relatively unique is that American law, like the English legal system it is derived from, is a common law system where the law is developed both from statues passed by the legislature and by judicial decisions made by courts. Our judiciary’s debates are over what the law is and how it should be interpreted—rather than what the law should be, which is the focus of a legislative body.

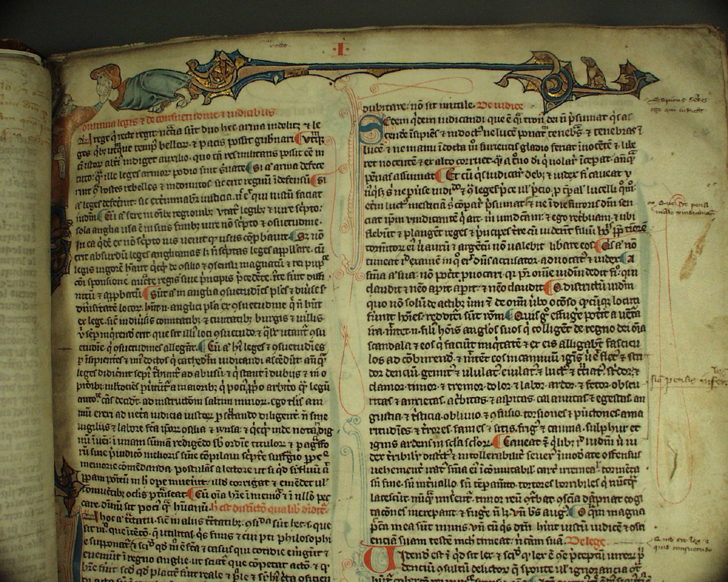

This dates back to the thirteenth century, the customs of various places were being compiled by royal judges in volumes such as the Norman Très ancien coutumier (“Very Old Customary”) and the English jurist Bracton’s De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae (“On the Laws and Customs of England”). These customals were early attempts to understand and catalogue the common law for royal judges; the first attempt to fully systematize this medieval common law on a national level was Edward Coke’s seventeenth-century Institutes of the Lawes of England. Coke’s work is still relevant today; it has been cited in over 70 US Supreme Court decisions.

Conversely, continental Europe, and most of the rest of the world, uses a statutory law system based, ostensibly, on Roman law. Broadly speaking, in these systems the law is what it is, and the job of the court is to apply it, not interpret it. Of course, the United States has statutes, as well, which are passed by the legislature; however, the concept of separation of powers, first articulated in its modern form by the Enlightenment philosopher Montesquieu (1689–1755), gives the Supreme Court the ability to strike them down via judicial review. The reasoning used in these decisions is derived from the principles of common law.

Originally, customary law systems were common on continental Europe as well. Roman legal principles generally were the foundations only of legal fields like as matrimonial law that were originally the province of the Church. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries however, and especially during the Napoleonic era, these were standardized into national law codes based on Roman principles. However, England retained its common law heritage, which it passed on to its colonies. Hence, “Anglo-American law.”

Words as Weapons

So, Sessions was factually correct. But, as Dorothy Kim has pointed out in another context, people should take care with how medieval history is deployed, since the past can so easily be “weaponized” as a tool of racism.

Sessions may have been careless, or he may have been intentional. And given Sessions’ reputation, he should have realized that this invocation of English history would be interpreted in the worst possible light. Whether he minds is another matter. His remark, to the lay observer, seems to be signaling that the “Anglo-American” origins of the legal system supports white supremacy.

Sessions likely did not realize the medieval context of his words. Whether he meant it as a medievalism or not, however, Sessions’ comments are part of a frustrating pattern where parts of our culture with medieval origins are weaponized to justify racist policies. It falls to each of us to remain vigilant, and to continue to push back against the use of the past to justify racism in the present.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.