Like just about everyone, I have been mourning the death of Robin Williams ever since I heard about it on Monday. I grew up with his movies. And his stand-up (along with that of George Carlin and Eddie Izzard) taught me more about the flailing absurdity of human existence than anything else did.

When I was in high school, Dead Poets Society touched me deeply, as it did many in my generation. This was not least because I wanted desperately to be an actor (though I was lucky that my parents were far more supportive than Neil’s [Robert Sean Leonard] father). But more than just that, the film articulated better than I could– then or now– the profound value of theatre, of literature and of the arts. In it, Robin Williams, through the character he played so well, showed us why the arts matter, and how a life without them can feel like a life not worth living.

My favourite scene– doubly so now that I am an academic– is the one in which the boys read the introduction to their Poetry textbooks, written by one Dr. J. Evans Pritchard, Ph.D.

Dr. Pritchard’s worthy introduction (which is apparently directly quoted from the venerable poetry textbook Sound and Sense by Laurence Perrine) demands that a careful reader analyse a poem’s greatness on scales of importance and perfection, and graph the poems accordingly. Obviously, the boys are told, this method will allow them to easily recognize true poetic greatness when they see it.

“Excrement.” says their teacher John Keating, played by Williams.

The boys then are asked– and in some cases forced– to tear out Dr. Prichard’s offending introduction. This accomplished, Mr. Keating tells them a secret:

We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for. To quote from Whitman, “O me! O life!… of the questions of these recurring; of the endless trains of the faithless… of cities filled with the foolish; what good amid these, O me, O life?” Answer. That you are here – that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. That the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?

I do not know what the verse of my life in this powerful play will read, but at the moment the one I return to over and over again is this:

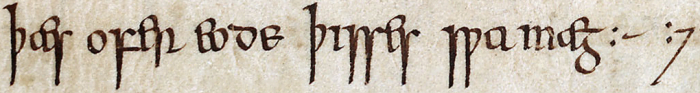

þæs ofereode þisses swa mæg*

That verse is from a tenth-century Old English poem from the Exeter book called “Deor”. It has been translated many times by scholars more able than I (like, for example, here), but I prefer my own rendering:

That’s overwritten; This also may.

Or, in longer form:

That part of the story has been overwritten; This may be too.

The poem in its totality is one of the first to have a verse-refrain structure. In it, the poet tells a series of tales. Though these tales– of Wayland the Smith, of Theodoric the Great, of Ermanaric of the Goths and others– were well known at the time, most have since fallen into obscurity.

But the poet only tells half of each story; he stops just as the hero or heroine hits a turning point– either at the height or in the depths. Then, repeated for each tale, the refrain:

That’s overwritten; This also may.

The characters, as the listener would well know, each suffered a turn. Wayland achieved victory over his captor, Theodoric’s empire collapsed, Ermanric’s cruel reign was overthrown. Each landed in the annals of history or became the stuff of legend. But the poet does not recount the end of their story– he simply says, at the climax: “That story changed. Your tale may too.”

Finally, and maybe most compellingly, he tells his own story. He once was considered a great poet with wealthy lord for his patron. But his position was given to another, leaving him bereft. But he takes some small comfort, that his own tale will change too.

He’s not saying that things will get better. The Anglo-Saxon poets were far too stoic for that sort of optimism. But, he says, things may change– and that has to be enough.

If there might be any positive change from Robin Williams’ death, it might be that we find more and better ways to help those grappling with depression. I have found that depression– situational or chronic– is a major problem within the historical professions. In my experience, more than half of my historian friends– myself included– have struggled with situational or chronic depression at some point.

Academia chews up and spits out its young.

In my own experience of it, the worst feelings are those that come when you feel as though the situation you are in will not– can not— change; that you are trapped, and just looking for a way– any way– to escape.

þæs ofereode þisses swa mæg

But things can change. They may not get better, but they do change. Life is an act of constant revision; the verse of our lives will continue to be written, rewritten and overwritten until we can not do so any more. It’s not much, but hopefully it’s enough to keep writing.

I have found this verse helpful in remembering that; I still do on occasion. It’s amazing that a thousand-year-old line of poetry can help keep me grounded– through the bad and the good. But, I suppose, maybe that is not so surprising after all. That is why literature, poetry, art, music– even that written by people a thousand years ago— still has the power to affect our lives. My students are often surprised at how much meaning and beauty can be found in medieval poetry and literature. Perhaps they have been so accustomed to the J. Evans Pritchards and Laurence Perrines of this world that they forget that art, poetry, or literature– from whatever age and in whatever language– is meant to grab you by the throat and not let go. In my experience, they should be more surprised if it were not meaningful, or powerful, or beautiful. We don’t read poetry because it’s cute.

What is your verse?

A Brief Word on Depression

I’m lucky. I had help. I had family and friends who were there to help me through the worst, an understanding employer who went above and beyond, and support offered by my University. But many don’t, or are (sometimes rightly) afraid that if they seek help that they will be stigmatized, their careers threatened, or be bankrupted by a broken healthcare system. This needs to change.

If you are struggling in silence with depression, I urge you to talk to someone. Things will change for you too, but only if you continue writing.

Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance: http://www.dbsalliance.org/

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: http://www.afsp.org/

Samaritans (UK): http://www.samaritans.org/

International suicide help numbers:

- Albania: 127

- Argentina: (54-11) 4758-2554

- Australia: 13 11 14

- Australia: 1300 22 4636

- Austria: 142

- Barbados: (246) 4299999

- Belgium: 106

- Botswana: 3911270

- Brazil: 141

- Canada – Greater Vancouver: 604-872-3311

- Canada – Toll free-Howe Sound/Sunshine Coast: 18666613311

- Canada – TTY: 1-866-872-0113

- Canada – BC-wide: 1-800-SUICIDE (784-2433)

- Canada – http://www.suicide.org/hotlines/international/canada-suicide-hotlines.html[1]

- China: 0800-810-1117

- China (Mobile/IP/extension users): 010-8295-1332

- Costa Rica: 506-253-5439

- Croatia: (01) 4833-888

- Cyprus: +357 77 77 72 67

- Denmark: +45 70 201 201

- Estonia (1): 126

- Estonia (2): 127

- Estonia (3): 646 6666

- Fiji (1): 679 670565

- Fiji (2): 679 674364

- Finland: 01019-0071

- France: (+33) (0)9 51 11 61 30

- Germany (1): 0800 1110 111

- Germany (2): 0800 1110 222

- Germany (youth): 0800 1110 333

- Ghana: 233 244 846 701

- Greece: (0) 30 210 34 17 164

- Hungary: (46) 323 888

- India: +91 80 2549 7777

- Ireland (1): +44 (0) 8457 90 90 90

- Ireland (2): +44 (0) 8457 90 91 92

- Ireland (3): 1850 60 90 90

- Ireland (4): 1850 60 90 91

- Ireland (5): http://www.mentalhealthireland.ie/information/finding-support.html[2] – free to call hotlines/text

- Israel: 1201

- Italy: 199 284 284

- Japan (1): 03 5774 0992

- Japan (2): 03 3498 0231

- Kenya: +254 20 3000378/2051323

- Latvia: +371 67222922

- Latvia (2): +371 27722292

- Liberia: 06534308

- Lithuania: 8-800 2 8888

- Malaysia (1): (063) 92850039

- Malaysia (2): (063) 92850279

- Malaysia (3): (063) 92850049

- Malta: 179

- Mauritius: (230) 800 93 93

- Namibia: (09264) 61-232-221

- Netherlands: 0900-0767

- New Zealand (1): (09) 522 2999

- New Zealand (2): 0800 111 777

- Norway: +47 815 33 300

- Papua New Guinea: 675 326 0011

- Philippines: 02 -896 – 9191

- Poland (1): +48 527 00 00

- Poland (2): +48 89 92 88

- Portugal: (808) 200 204

- Romania: 116123

- Russia (1): 007 (8202) 577-577 (9am – 9pm)

- Russia (2): (7) 0942 224 621 (6pm – 9pm)

- Samoa: 32000

- Serbia: 32000

- Serbia (2): 0800-300-303

- Serbia (3): 0800-200-301 (18-08h)

- Serbia (4): 024/553-000 (17-22h)

- Singapore: 1800- 221 4444

- South Africa: 0861 322 322

- South Korea: http://www.suicide.org/hotlines/international/south-korea-suicide-hotlines.html[3]

- Spain: 902 500 002

- Sweden (1): 020 22 00 60

- Sweden (2): 020 22 00 70

- Switzerland: 143

- Thailand: (02) 713-6793

- Ukraine: 058

- Uruguay: *8483 (24/7, free from most cellphones)

- Uruguay (2): 0800 8483 (free between 19 – 23 hrs)

- Uruguay (3): 095 738483 (24/7)

- United Kingdom (1): 08457 909090

- United Kingdom (2): +44 1603 611311

- United Kingdom (3): +44 (0) 8457 90 91 92

- United Kingdom (4): 1850 60 90 90

- United Kingdom (5): 1850 60 90 91

- United States of America: 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

- Zimbabwe (1): (263) 09 65000

- Zimbabwe (2): 0800 9102

* The original is more literally translated as “That’s overridden”– meaning something which has been left behind, or ridden over (imagine, for example, having ridden over a bridge). But for myself I prefer the slight change to overwritten– not just because I (along with most people) write more than I ride. And it is a good revision, in my opinion, because it retains the meter and has assonance with the original while retaining the same sense.