Editor’s Note: This article is a follow-up from an article I wrote for Inside Higher Ed, “The Humanities Must Unite or Die.“

I recently met a young woman struggling over the decision of whether to go to college. She was enrolled in an excellent program for bright high-schoolers from low-income families, which was intended to give them a leg-up into STEM majors (and then, STEM careers). Any university would be lucky to have her—she is smart, motivated and articulate. She would be a first-generation college attendee. But she was torn.

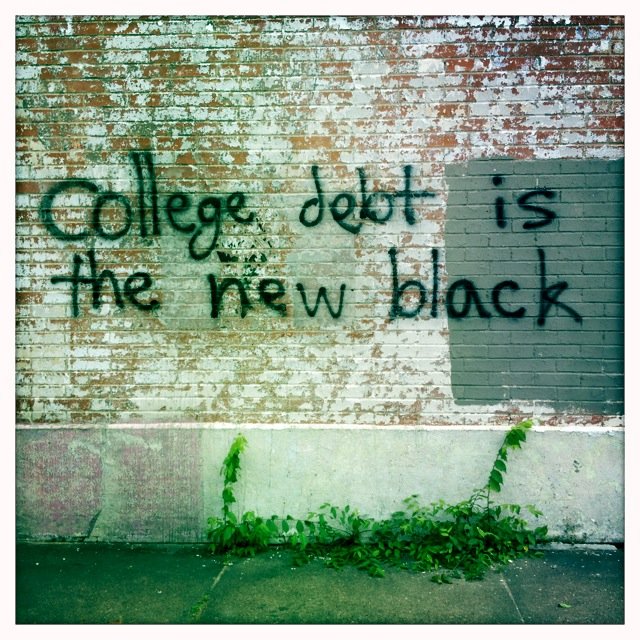

The prospect of a five-figure loan to finance her education—while her parents struggle to make ends meet—felt risky, even irresponsible. She wondered whether, instead, to take a job right out of high school, particularly since she was unsure whether she even liked the STEM subjects promoted by the program.

STEM has been promoted by programs like this one—not to mention by government programs and presidential initiatives—as the sure path to a lucrative career, despite numerous studies indicating that it is little better than the arts and humanities at providing jobs after graduation. As a result, as college attendance rates have dropped for low-income students, those low-income students who remain have chosen to major in STEM fields far more than the arts and humanities.

The Washington Post recently reported a disturbing trend: between 2008 and 2013, “college enrollment among the poorest high school graduates—defined as those from the bottom 20 percent of family incomes—dropped 10 percentage points… the largest sustained drop in four decades.” This is particularly alarming because, “more than half of the nation’s K–12 public school students are considered to be from low-income families.” Ten percent of this population represents a very large number of people, including, possibly, the bright, conflicted young woman I met.

The Role of the Humanities

Whenever the conversation about how to rescue the arts and humanities turns toward better promoting the utility of arts and humanities degrees on the job market, a common refrain is raised: scholars of these fields should be purists, the “keepers of the flame” of their disciplines. Any other priorities make them a “sellout.” Paul Jay and Gerald Graff identified two types of these critics: “Traditionalists” and “Revisionists.” To them, “Traditionalists argue that emphasizing professional skills would betray the humanities’ responsibility to honor the great monuments of culture for their own sake.” By contrast, Revisionists “argue that emphasizing the practical skills of analysis and communication that the humanities develop would represent a sellout.”

The argument against employability and utility becomes a moral one: promoting the utility of the arts and humanities is a creeping departure from the uplifting experience of studying Macbeth, the Magna Carta, or Wittgenstein purely for the sake of knowledge. It conjures the ideal of the gentleman-scholar, where learning should be for learning’s sake absent gross material concerns.

Rooted in Victorian ideals as they are, this argument ignores perhaps the greatest functions of the modern university: as a route out of poverty. And arts and humanities departments have an important role to play in this.

This goal was evident at the very outset of the modern American University system. The Morrill Land-Grant Acts, which created the land-grant college system in the US, said the purpose of this system was “to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” Employability went hand-in-hand with liberal arts education for the benefit of the working classes. And that system still works: despite our concerns about the growing costs, a college degree remains an excellent investment in terms of earning power. The wage gap between those with a college degree and those without it is higher than ever.

Where the Arts and Humanities Come In

But studies have shown that, once this investment is made, employability after college has much less to do with students’ chosen major than their overall success in school, the skills they can develop and articulate, and the connections they forge. High-flyers in Women’s Studies are more likely to succeed than below-average students of Electrical Engineering. Perhaps employers respect a good GPA, but more likely the cause of success is the student: someone who is smart, passionate, motivated, and hardworking is likely to express those traits outside the classroom as well as inside it.

Further, though most majors seem to be roughly equivalent in terms of employability, students have different passions and aptitudes. A student bored by Milton may be set alight by Computational Algebra—or vice-versa. By eschewing promoting the value of our disciplines to those very students who are most worried about its value for their future, we do a disservice both to them and to ourselves. Some of those students surely are scared to take a degree in the arts or humanities, or feel pressured to take the “safer” road offered by STEM—but they may not have the passion or ability to truly succeed in STEM, like they could in the arts and humanities.

Ultimately, it does not need to be an either/or proposition. Showing the value of studying the human disciplines in the marketplace does not detract from the joy and meaning derived from studying them. We can promote ourselves as a discipline that helps to forge thoughtful, well-rounded individuals and enables them get jobs. It is not just the former that expresses our common ideals. Arguing for employability in the arts and humanities is not about crass material concerns, it’s about our ability to help those of our students who need it the most.