But will God indeed dwell on the earth? behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee; how much less this house that I have builded? – 1 Kings 8:27

The world watched with horror and sadness as Notre Dame, the iconic and beloved cathedral of Paris, suffered immense damage in a catastrophic fire on April 15, 2019. As a Catholic, a medieval historian, and a Francophile, I was heartbroken to watch this historic landmark engulfed in flames. Notre Dame represents both a sacred space and the life’s work of the hundreds of craftspeople who worked on it, drawing over 12 million visitors annually.

It’s difficult to pick just one aspect of what makes Notre Dame so majestic for me. Ever since I began studying the French language in junior high, which included many lessons on Francophone culture, I loved learning more about Notre Dame. When I turned 18, I was fortunate enough to visit my relatives in Paris, and first on my must-see list was a visit to the cathedral. As I sought to take it all in: the sculptures, gargoyles, relics, flying buttresses, and stained glass windows, I was overcome with a sense of awe. My neck craned to glimpse every detail of the medieval cathedral as my aunt and I slowly made our way through the interior. It was this first-hand encounter with Notre Dame that helped propel me to study the Middle Ages both in college and in graduate school.

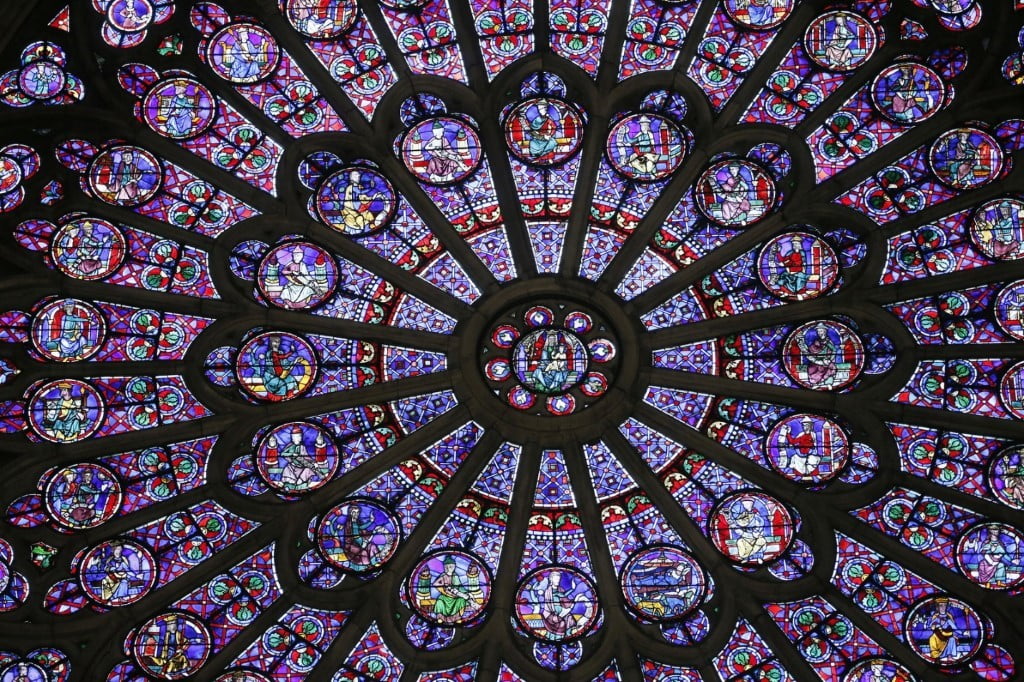

When I tell people that I am a medieval historian, the most common response is, “Oh, you mean the Dark Ages?” My initial retort is to list some of the achievements of the Middle Ages that make the term “Dark Ages” a misnomer. But, if I’ve managed to pique their interest, I like to explain that the people of the Middle Ages were utterly fascinated with light and color. I often point examples of Gothic architecture, such as the stained glass windows of Notre Dame, as one of the crowning architectural achievements of the Middle Ages. The distinct pattern of this rose window, which was composed of thousands of pieces of delicately placed colored glass, became a defining aspect of later Gothic architecture. Although approximately eighty cathedrals and five hundred large churches were built in France concurrently with Notre Dame, she is singular among them in her sublime beauty.

Under the direction of Bishop Maurice de Sully, the construction of Notre Dame first began in 1163. It took over a thousand manual laborers nearly two centuries to complete the cathedral. It was during the thirteenth century that the famous flying buttresses were installed. These external braces, which not only supported the walls, but allowed them to higher and thinner, which enabled the installation of the stained-glass windows. Under the direction of King Louis IX, (who was later canonized as St. Louis) in 1260 the three rose windows were installed. This brought more light into the church, and drew worshiper’s eyes upward. It was also during this time that the original spire was erected (which, after enduring centuries of wind damage, was removed in the late eighteenth century). It was like a finger pointing toward heaven.

Not only is Notre Dame a testament of the many artistic and architectural developments of the period, the cathedral also bore witness to many other intellectual feats of the Middle Ages. The emergence of polyphonic (multipart) music stems from a group of composers who worked at the Notre Dame cathedral from approximately 1160 to 1250. The university at Paris, developed throughout the twelfth century, emerged from the famous cathedral school at Notre Dame. This, along with the universities at Oxford and Bologna, came to form the basis for what is now our modern university system.

Central to Notre Dame’s historical significance, since its earliest days, it has served as a place for prayer among the masses. Because of its many statues and stained glass windows depicting biblical figures, Notre Dame, like many medieval cathedrals, was known as a liber pauperam (“poor people’s book”). These images were meant to serve as religious instruction for those could not read. The Cathedral is also a celebration of the importance of the Virgin Mary to Catholic Christians. Not only is the Cathedral named after her, but there are 37 representations of her throughout the cathedral. Most notable is “The Portal of the Virgin,” where Mary is flanked by angels and saints. This particular Marian portal is often was referred to as super rosam rosida (“the rose of roses”), a name that emerged from twelfth-century poet Adam de Saint-Victor.

Since the Middle Ages, throngs of Catholic Christians have made pilgrimages to Notre Dame, praying to its patron saint, Mary, for divine intercession and protection. Most movingly on Monday, crowds in Paris began to sing “Ave Maria,” seemingly to honor the church and, for some, perhaps to seek Mary’s intercession to save her church.

The fire thankfully was extinguished. The damage is still being assessed, and proposals for its future are being considered. So, this is a good moment to recall moments in Notre Dame’s history when the building became the focal point of contentious debate about the use of a sacred space. During the French Wars of Religion (a period of unrest between Roman Catholics and Huguenots, who were Reformed/Calvinist Protestants, between 1562 and 1598), the Hugenots destroyed some of the Cathedral’s statues, declaring them idolatrous. Another violent set of assaults on Notre Dame took place during the French Revolution, when the cathedral represented, to many, the antithesis of the Enlightenment. It was looted and renamed the “Temple to the Goddess Reason.” Many of the statues of Mary were removed at this time and replaced by statues to the Goddess of Liberty. Thought to be statues of French kings, 28 statues of biblical kings were beheaded: their heads were only discovered in a 1977 excavation. On April 18, 1802, as part of an agreement between the Catholic Church and Napoleon Bonaparte, it was rededicated as a Catholic church. Napoleon later used it for his coronation as emperor in 1804.

Despite being given to the Catholic Church by Napoleon, Notre Dame remained half-ruined. Attempts at restoration remained stagnant until, in 1833, Victor Hugo used the cathedral as the backdrop for The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He did this to inspire in people an affection for the decrepit, neglected edifice and, through a romantic idea of it, motivate the populace to refurbish what Hugo called “a vast symphony in stone.” Moved by Hugo’s thousand-page love letter to Notre Dame, a clamor arose to restore the cathedral to its former glory. The Commission on Historical Monuments was formed and in 1844, King Louis Philippe ordered the church to be restored, which included the re-glazing of the stained glass windows, the addition of a new organ, as well as the addition of the now-famous gargoyles. It was also during this restoration that the spire that fell on Monday was built.

In World War II, the stained glass windows of Notre Dame only sustained minor damage, mainly from stray bullets during the liberation of Paris in August 1944. As part of the celebration of Paris’s liberation, a special mass was held in Notre Dame, which was attended by Charles de Gaulle. In 1963, marking the 800th anniversary of the Cathedral, Notre Dame underwent a series of restorations which helped remove some of the accumulated dirt and grime, and ultimately emerging all the more beautiful.

Now, the cathedral lies gutted by natural disaster. It is, of course, not unique in this; natural disasters have ravaged some of the greatest sacred architectural feats. In 558, an earthquake caused the collapse of the dome of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom), the cathedral in the Byzantine Empire’s capital city of Constantinople, (subsequently a mosque, and now a museum in modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). Subsequently, Hagia Sophia survived a fire in 859 and as well as a second earthquake in 869. The Great Fire of London in 1666 destroyed 87 parish churches and St. Paul’s Cathedral, and an earthquake in 1997 destroyed one of the most famous frescoes of the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. In 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake destroyed several Buddhist temples in Nepal, including two sites that dated from the 5th century. And on the same day as the fire at Notre Dame, the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam, also caught fire, though thankfully it only suffered minor damage. But it has been rebuilt multiple times, particularly following the damage wrought by massive earthquakes in 746 and 1033.

And this is not to mention the destruction of sacred sites regularly perpetrated by violence and war, from the shockingly regular attacks on African-American churches, mosques and synagogues in the US, to the wholesale destruction of ancient holy sites in Iraq and Syria by ISIS during the civil war.

But just because the destruction of sacred places is common does not make them less shocking. And just because they will be rebuilt does not make them less worthy of grief.

The tearful reactions around the world on that day in April point to how beloved Notre Dame is, as both a sacred site and a historical landmark. It’s difficult to put into words how much Notre Dame means to so many groups of people: Catholic Christians who flock to it as part of a sacred pilgrimage, scholars who appreciate its unparalleled place in history, tourists who are awestruck by its magnificence. Fourteenth-century French philosopher and theologian, Jean de Jandun, in his 1323 Tractus de laudibus Parisius (Treatise on the Praises of Paris), offers one of the best arguments for Notre Dame’s distinctive beauty and why so many of us grieved the destruction wrought by the fire,

“In fact, I believe that this church offers the carefully discerning such cause for admiration that its inspection can scarcely sate the soul… that most glorious church of the most glorious Virgin Mary, mother of God, deservedly shines out, like the sun among stars.”

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.