In fourteen-hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue—and discovered that the Earth, despite the beliefs of the Catholic Church and Spanish royalty—was round.

Right?

Absolutely. Not.

People—ancient and medieval—have known the Earth is spherical since at least the 6th century BCE. Ancient Greek mathematician Pythagoras was likely the first to propose the idea, though his argument was based on philosophy and aesthetics rather than mathematics and astronomy. But physical evidence that the earth was round followed, thanks in part to Aristotle and Eratosthenes. The knowledge was not lost with the end of the Western Roman Empire, either. In The Reckoning of Time, Bede (who lived circa CE 673-735) refers to the Earth as an “orb” and says that “it is not merely circular like a shield or spread out like a wheel, but resembles more a ball.” This idea was repeated by philosophers, mathematicians, and astronomers throughout the Middle Ages.

And yet, the idea that medieval people believed in a flat Earth is one of those maddeningly tenacious pieces of “common knowledge.” It’s one of those pieces of knowledge trotted out when people want to claim how “stupid” or “backward” medieval people were.

Fast forward to the present, and everything old is new again. There are a surprising number of people—who generally call themselves “flat-earthers”—who promote the belief that the world is flat. The Guardian recently released a short documentary video about them. Netflix has a feature-length documentary. This profoundly retro conspiracy theory has particularly found a home on the internet, where it has been notoriously promoted by popular YouTube stars like Logan Paul.

While it’s possible some of these modern flat-Earthers may think they’re carrying on a tradition from the Middle Ages, their beliefs actually originated in the 1830s. And not at all coincidentally, that is roughly the same time that the myth that medieval people thought the world was flat was born, as well.

The Round Earth Rebellion that Never Was

These ideas and their history have been extensively debunked by Jeffrey Burton Russell in his excellent book Inventing the Flat Earth. The belief that the people of the Middle Ages thought the Earth was flat and were re-educated by Christopher Columbus is an example of the widespread myth that medieval people were either stupid, ignorant, or both. But if you look under the hood of this notion, it actually says less about the Middle Ages than it does about the people who championed the idea. Take 19th century French philosopher Auguste Comte, whose theory of positivism says that human intellectual and social development happened in a straight line from Neanderthal to his own image of a refined gentleman. Claims like this fundamentally, and in some cases purposefully, misunderstand the historical record so that the perpetrators can feel superior to the past—and were often used to justify racism, colonialism, and imperialism.

Medieval intellectuals knew very well that the Earth is a sphere. Medieval philosophers and theologians had access to the Greek and Arabic works of “natural philosophy” (a.k.a. “science”) in Latin translations. Bede, for example, demonstrated that the changing length of daylight in different seasons was due to the sphericity of the Earth. Roger Bacon (c. 1219-1292 CE) argued that the Earth is spherical and that other lands on the opposite side of the globe existed and could be visited. Scientists discussed the rotation of the Earth and the other planets, and while they did believe that the Earth was the center of the universe, they believed the universe itself was spherical. Even the author of Mandeville’s Travels, who believed in (or at least wrote about) people with giant feet to shade their heads, wrote about a spherical Earth, time zones, and people not falling off the other side of the planet.

With all the evidence that medieval scholars knew that the Earth is round, where did we get the idea that they believed the Earth was flat? The core of the idea can be traced back to 18th– and 19th-century progressivists, who decided that science and religion—that religion specifically being Roman Catholicism—had always been at war. John William Draper, for example, argued that religion was based on magic and thus antithetical to science; he also blamed St. Augustine in particular for turning the Bible from a model for a moral life into

“the arbiter of human knowledge, an audacious tyranny over the mind of man.”

Historians such as William Whewell and Andrew Dickson White argued that Catholicism was inherently opposed to progress; creating an ignorant medieval world allowed eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Protestant thinkers to put down the Catholicism of their day. Historians and biographers cherry-picked their “medieval” sources. They insisted that people like Cosmas (who wrote in CE 500s, at the very beginning of the Middle Ages) and Lactantius (who wrote around CE 250-375, well before the Middle Ages), who did argue for a flat Earth model were much more influential than they actually were. They also pointed to maps by people such as Isidore of Seville and Saint Augustine—maps that were spiritual or conceptual descriptions of the world and not practical navigational maps—claiming that 15th-century navigators relied on these maps to sail. Those maps were part of religious texts, and would have only ever seen a ship if they were being carefully transported in a monk’s belongings!

For other nineteenth-century writers, the medieval flat-Earther myth was part of a nationalist project, one that painted Christopher Columbus as a scrappy, rebellious hero rather than the genocidal asshole he really was.

American writer and historian Washington Irving was one of the first to promote this myth. He wrote A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828—a book which freely mixed fact and fiction to create a “Hero Columbus,” beset by naysayers of every type, fighting against “errors and prejudices, the mingled ignorance and erudition, and the pedantic bigotry” of everybody who wasn’t him. Similarly Antione-Jean Letronne, an intellectual prodigy from France, claimed that medieval people who knew the Earth was round were “outliers” and that the Catholic Church “forced” people to believe in a Biblically-mandated flat Earth.

The public believed these men because they were eminent scholars. But they built their body of knowledge about the beliefs of the medieval people by citing each other; intellectual echo-chambers are nothing new.

Why were scholars so eager to buy into the lie that medieval people thought the Earth was flat? It comes down to the same needs behind many of the erroneous beliefs about the Middle Ages: modern people need somewhere to put ignorance, backwardness, and barbarism. They need to feel superior to someone else. The Middle Ages is, very often, where that need ends up. “Flat Earther” is a useful shorthand for willful ignorance, usually used as code for people who refuse to accept modern science, or a slightly-more polite way of calling someone “barbarian.”

But that raises another question: what has caused a group of people today—who have access to much more advanced science including photographs of the spherical earth—to insist that the Earth is flat? Why do they insist upon the idea that the spherical Earth is a conspiracy perpetrated on humankind by scientists, governments, and “deep state operatives” for the last 3,000 years?

Flat Earth Utopia

The modern argument really started with nineteenth-century Englishman Samuel Birley Rowbotham. Rowbotham wrote a pamphlet in the 1830s that he called Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe under the pseudonym “Parallax.” This was first published in 1849, and expanded into a book in 1865.

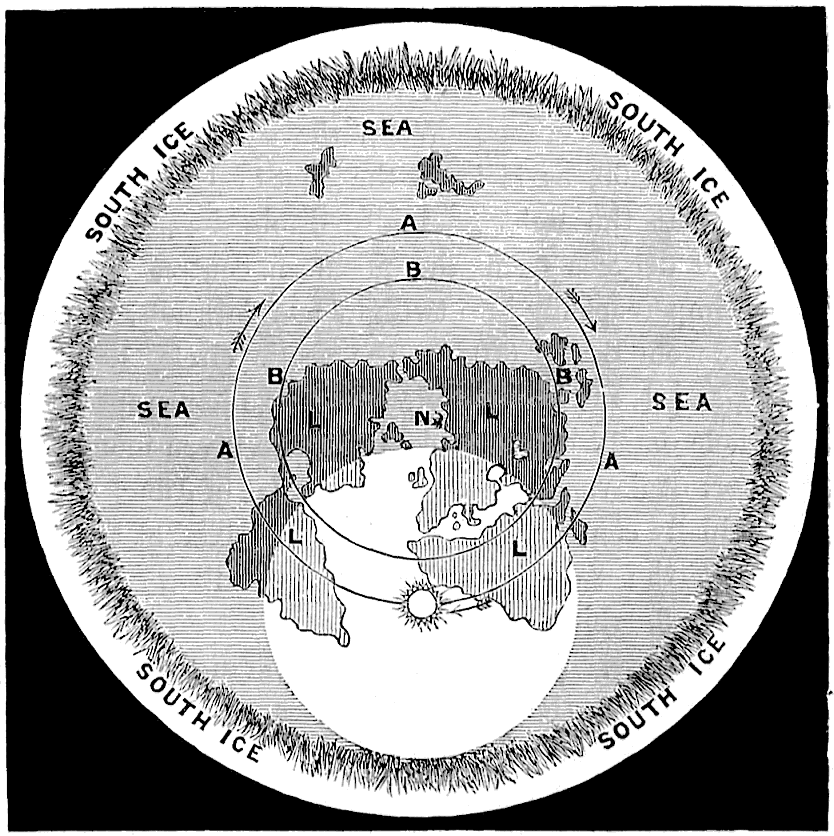

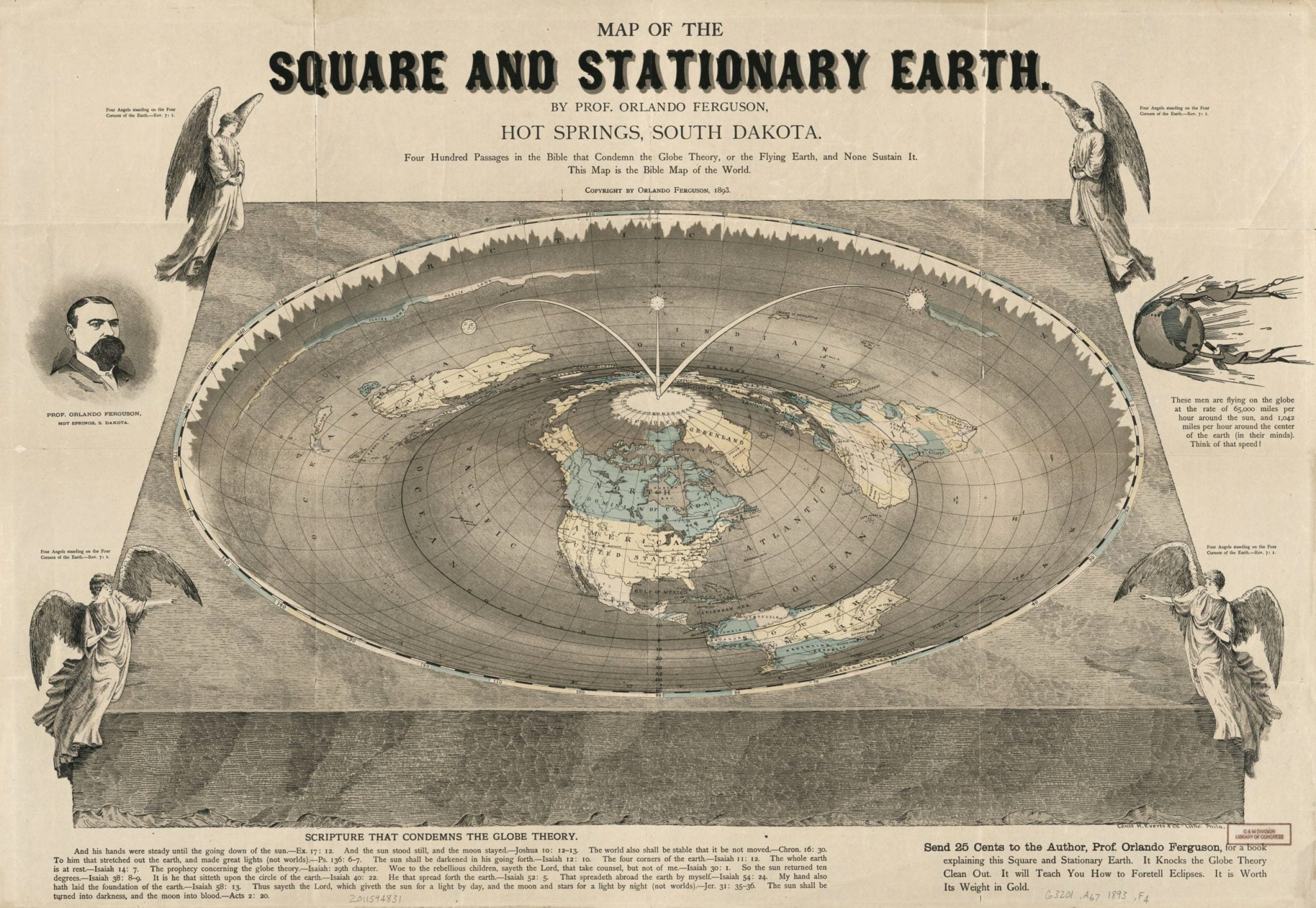

In it, Parallax argues for a Christian Fundamentalist, biblically literal interpretation of the world—that the Earth is flat, was created in six literal days, is only 6,000 years old, and is headed rapidly toward the apocalypse. His conception of the Earth was that it is a flat disc with the North Pole at the center and a massive ice wall around the outside edge.

He did not say anything about whether there were White Walkers on the other side, so let’s assume not.

Rowbotham came up with some very complicated projections to explain the cycles of night and day, the seasons, and eclipses. But central to his thesis was his attack on the scientific method, which he claimed “take[s] the liberty of inventing certain principles and hypotheses” and then creating mathematical models to prove those hypotheses.

The scientific method absolutely does not work this way. But that is the straw-man that he argues against.

Instead, he argued for logic and observation—“that natural and legitimate mode of investigation.” At the end of his pamphlet, he argues that Newtonian theory is “a prolific source of irreligion and atheism” and he argues that to reject the Biblical model of the Earth as flat is to reject all Biblical teachings. He certainly knew how to stake out an extreme position.

Since then, the flat-Earth belief has followed both a Biblical literalism and an anti-modern-science thread, not always at the same time by the same people. If you’re interested in how the belief propagated down through the generations and the people who pushed it, Christine Garwood’s book Flat Earth: The History of an Infamous Idea provides a deep dive into it, but here’s a brief summary:

Rowbotham’s followers (who eventually established The Universal Zetetic Society in 1893) did a bunch of stunts trying to get people to prove the Earth is spherical while rejecting every bit of evidence anybody brought forward. For example, in 1870, John Hampden offered a cash reward for proof that the Earth was spherical. Alfred Russell Wallace took him up on it.

Fun fact: Wallace devised his own theory of evolution from natural selection that was published at the same time as Darwin’s; Wallace was no scientific slouch.

Wallace set up a very basic experiment—three sticks in a line along a canal between two bridges—to show the drop in elevation due to the curvature of the Earth. According to Wallace, Carpenter declared that “the fact that the distant signal appeared below the middle one as far as the middle one did below the cross-hair, proved that the three were in a straight line, and that the earth was flat.” The experiment, of course, showed the exact opposite, but Carpenter was not one to let evidence get in the way.

Across the pond, in 1899, preacher and faith-healer John Alexander Dowie established the town of Zion, Illinois, as a Christian utopia; it became the major center of American flat-Earth belief. Unfortunately for Zion, Dowie was greedy and vastly narcissistic. He declared himself the reincarnation of the prophet Elijah and bankrupted the town so he could live in luxury. Ultimately, the people of Zion rejected Dowie’s teachings and voted to become secular.

Samuel Shenton established the International Flat Earth Research Society in 1956 and spent his life trying to prove that the space program was faked—and also, somehow, that the space program actually proved the Earth is flat. His successor, Charles Kenneth Johnson, brought the conspiracy theories.

- He claimed that Columbus had discovered the Earth was flat, not round, on his voyage.

- He claimed that Satan had convinced Copernicus that the Earth was a sphere.

- He claimed that NASA continued the lie about the earth being a sphere because it created jobs.

- He claimed that prominent science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke wrote and directed the moon landing.

- He claimed that the moon landing was shot in Meteor Crater in Arizona.

- He claimed that the Challenger disaster was either a plot by NASA to cover up that they couldn’t actually leave the atmosphere or God’s divine judgment for trying.

- He even claimed that O.J. Simpson’s role in 1977 film Capricorn One (about a faked Mars landing) is the reason he was “framed” for murder.

None of these claims are true. Many are provably false. But that does not matter in the mind of a conspiracy theorist like Johnson.

All of these people had different reasons for believing in—or pretending to believe in—a flat Earth. Some were religious, some were concerned about government overreach, and some were flat-out cons. But their beliefs spread and persisted, undeterred by science or evidence.

Wired Flat-Earthers

In the 21st century, flat-Earth belief has grown. But at the same time, it has grown even more perplexing. Partially this is because of the rise of the Internet. The Internet allows for an unprecedented ability to spread information and scientific knowledge. But on the flip side, this same function allows the spread of misinformation and self-curated echo chambers where conspiracy theories flourish.

Poe’s Law helps us understand why. Poe’s Law is a theory of Internet culture identified by Nathan Poe in 2005, where he stated:

Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humor, it is uttrerly impossible to parody a Creationist in such a way that someone won’t mistake for the genuine article. [sic]

Today, this is often generalized to say that any satire of any extreme position is indistinguishable from sincere belief in that position. So, it is nearly impossible to tell which of the people on the many websites, forums, Facebook groups, and conferences devoted to belief in a Flat Earth are true believers, and which ones are “just trolling.” Likewise, some other proposed beliefs among these people, such as that there is “no such thing as forests,” seem so outlandish that most people won’t be able to understand how believers could possibly reach these conclusions.

Flat-Eartherism is so mixed up with other conspiracy theories that it can be difficult not to dismiss these people as kooks and ignore them. But their beliefs—those of them who truly believe it—are a symptom of a larger societal problem and also a function of human psychology. Some of it, especially the strain passed down by Rowbotham, is anti-intellectualist. Broadly speaking, people tend to like understanding things, and dislike being unable to understand them. When they find new information challenging, many choose instead to fall back on a predetermined worldview or simply believe their own senses—even when those senses are incapable of perceiving something like the size of the globe. So when scientists tell them their senses are wrong or inadequate, they’ll push back.

The other strain is conspiracy belief, which has its own set of psychological indicators, but is tied up in the human brain’s tendency to find patterns where there are none (part of what psychologists call the “conjunctive fallacy”). As we can see from the list of theories Johnson introduced to the flat-Earth idea, conspiracy theories tend to travel in packs and are highly political in nature. But they require social interaction to thrive, which the Internet has provided in spades. Conspiracy belief also correlates with feelings of isolation, powerlessness, and overactive pattern-finding.

Essentially, conspiracy theories give people a sense of control over an uncontrollable world, or at least a reason why they can’t control it—because “the deep state” or a “one-world government” or the Illuminati (or all of the above) is actively working against them and people like them. The flat Earth conspiracy, in particular, encourages people both to believe their own senses over science, and to think the government is hiding something out beyond the “ice wall” that is Antarctica. They want to have their conspiratorial cake and eat it too.

A Fundamentally Modern Flat Earth

What is truly remarkable is the medieval flat Earth myth and modern conspiracy theories actually have no history in common. Modern flat-Earthers are not carrying on a belief system from the Middle Ages. They do not, for the most part, even claim that they are. Yet both uses of the flat Earth theory are ways for people to feel superior to others. If medieval people thought the Earth was flat, we (who do not believe such silly things) can show how much more developed and intelligent we are than them.

On the flip side, believing in the conspiracy is like betting on a huge long-shot to win a horse race. Sure, it may be risky. But imagine the mental rewards if you win: if all of science is proven wrong, and NASA et al. are found to have been lying to us for 3,000 years, then the flat Earth conspiracy believers can claim to be so much smarter than everyone else. That’s why they use every intellectual trick in the book to call the “race” in their favor; they’ve bet their reputation, and even their identity, on a ridiculous long shot. They need to win.

In either case there are innate human needs to be right, and to feel better than others. This need feeds both of these beliefs—the belief that we are better than medieval people, and that the earth is flat. Ultimately these needs can lead people to believe the unbelievable in their quest for superiority.

It can be tempting to blame the Internet for conspiracy beliefs. It’s tempting to want to burn the whole Internet to the ground. But conspiracies have been around for as long as humankind has. Research has shown that laughing at people who cling to conspiracies only makes them cling harder. As with so many things, prevention is the best way to combat conspiracy belief; psychologists have found that presenting scientific research to people before they’re exposed to conspiracy theories is key to helping them to not fall for these theories. Education is vitally important, both for teaching facts, for developing critical thinking abilities, and for preventing the spread of the dangerous misinformation running wild on the internet.

So, at the risk of ruthless self-promotion, make sure to share this article, and others on this subject, with everyone you know. It might be the only thing standing between them and building a homemade, steam-powered rocket in hopes of proving the Earth is really flat.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.