Several years ago, I became good friends with a woman who had been abused by her previous partner. Abuse is shockingly common; her experience is not all that unusual. She confessed to me that she would wake up bolt-upright at 3am, shaking from night terrors. Things that would remind her—even just a little—of her previous partner would send her into a tailspin. Even saying his name could overwhelm her and give her a full-blown panic attack.

Her story is, sadly, not that unusual. But what made her experience particularly bad was that she had an exceptional memory—something approaching either what psychologists term an Eidetic memory or Hyperthymesia, where one can easily recall with great precision images and events from your past. Being able to remember everything from where you put your keys to the little wrinkles around your first child’s eyes may sound like a dream, but for her, the experience was a waking nightmare.

For her, counselling and therapy helped her to eventually make the memories—if ever present—less intrusive in her daily life. It allowed her, if not to forget per se, to choose what to remember on any given moment.

And perhaps ironically, that is one of the chief ways in which we, as a society, use history: we use it in order to decide what to remember and what to forget.

Forgetting as History

When creating a history, whether it be a scholarly book or the musical Hamilton, the historian’s job is not simply to uncover a story, unvarnished, which lies waiting to be told. Instead, one of the key processes involves picking which story is the most believable, the most interesting, and the most relevant to that particular narrative. But stories will always fall to the wayside.

Nineteenth and twentieth century histories are often lambasted for choosing only to tell the stories of people in positions of power and privilege. In the 19th century this took the form of the Great Man theory which argued that history was shaped by the actions of a few extraordinary men—and thus, it was those men’s stories who were the ones worth telling. Of course, these great men tended to be white, and rich, and, well, men—leaving the history of women, the working class, colonized people and people of color out of the picture entirely.

You know what they would call women’s history, African-American history, or LGBT history in an equitable society? History.

But, within the historical profession it hadn’t widely been considered history until the 1960s 70s and 80s, as new crops of historians were hired—spurred by the civil rights and feminist movements—and put women and people of color back into the historical narratives. Those who were unfairly forgotten are being remembered, and, bit by bit, their voices recovered.

However in the digital age, the concern has shifted—from historical amnesia to an historical eidetic memory, and an emerging inability to forget.

In her book Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture, Alison Landsberg describes the mass media a sort of collective memory bank, a “prosthetic memory”. In this bank is stored memories that belong to us collectively rather than any individual—though they are created and shaped by the mass of individuals who produce, consume, and reproduce them. I remember the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the election of Barack Obama (for example) as a combination of my personal recollections entwined with the images of it presented to me in the media.

The internet has brought this to a new level, where personal memory and the public record bleed into one another. The internet is, at once, ephemeral and remarkably durable and it is famously difficult, once something has been posted there, to have it removed—especially if there are even a small group who want to keep it there. This has had profoundly negative consequences, particularly when it comes to online harassment, especially of women.

For example, in 2014, around 500 nude photos of female celebrities were leaked on the internet by hackers and spread widely by the users of 4chan and Reddit in what became known as “the Fappening”. This was not the first time that the private had been made public—especially in celebrity culture. But the collective eidetic memory of the internet made the violation—which has been likened to sexual abuse—enduring in a way previously impossible. These hackers have become historians, deciding what should be known, and remembered, about their celebrity victims—and maintaining those curated memories through their websites and hard drives.

Similarly and even more horrifyingly are the abusive trends of doxxing and revenge porn.

Abusive Electronic Memories

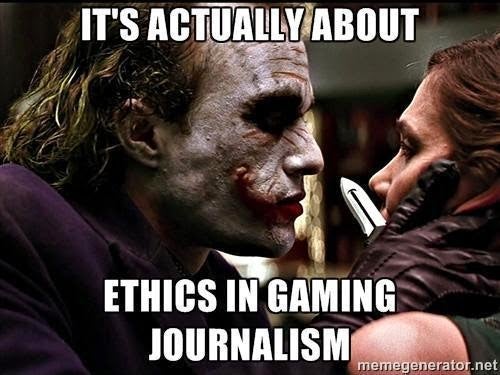

The word “doxxing” came into the mainstream during the recent “Gamergate” controversy where a group of men, part of a larger movement ostensibly aggrieved about a lack of “ethics in games journalism”, released the personal information—including personal emails, phone numbers and addresses—of a number of female journalists, activists, and ordinary people. This was intended to terrorize their victims into capitulation, and has led to several of these journalists leaving the industry.

Similarly, but even more perversely, revenge porn is a phenomenon wherein an individual publically posts pornographic images or videos of an ex-lover without their consent. This typically includes doxxing information (name, address, place of work) attached. The consequences, both personal and professional, can be dire for victims. It has lead to in-person harassment, blackmail, and worse.

Both of these phenomena constitute a wretched form of history-making, where, through the durability of the internet they are able to make the personal the public, and the ephemeral lasting. The objects of a true historian’s inquiry cannot—perhaps even should not control their narrative. Our understanding of Julius Caesar is not constructed through only his self-representation, but in the way others described and reacted to him. But at the edge of memory and history, a loss of autonomy over one’s narrative can be incredibly damaging.

The latest intersection of memory and history comes through a “feature” of Facebook—“Facebook memories”. Currently, by default, Facebook occasionally presents users with posts they made in the past—from one to five years ago, with the option to share these memories in the present. This is intended—and presented—as a pleasant walk down memory lane. But it comes with a host of unintended consequences. Similar to my friend whose eidetic memory would shock her with intrusive memories of her abuse, Facebook’s memory of our lives has become intrusive. For those who live a charmed life devoid of disappointment or heartbreak, this feature is fine. But they’re the only ones—Facebook thrusts in its users faces the good and the bad equally. And this cannot be helped if Facebook were to only show the users posts that others had “liked”—imagine the case of a couple who has lost a child. Every joyful memory served to them by the service could be a new knife in the heart.

This is one of the great challenges of our age. How can we ensure that the revolutionary tool—this persistent prosthetic memory—allows us to remember and forget—and to be remembered and forgotten? How can historians—themselves always hungry for data and minutiae of people in the past—contribute to this deeply ethical debate over memory and history?