“YOU DIED.”

These are the words that any player of Dark Souls is intimately familiar with. They are an accusation. It flies in the face of more familiar video game end screens like: “Game Over” or “You are Dead”. The game isn’t over. You need to try again. You need to do something different.

Failure and death are the nearly synonymous with the Dark Souls series. With episodes released in 2011, 2014, and 2016, they are a nightmarishly difficult series of action games. The Dark Souls series has made a profound impact on how video games incorporate difficulty into their mechanics. However, it is also worth considering how the Dark Souls series difficulty unsettles knighthood as a symbol of invulnerability.

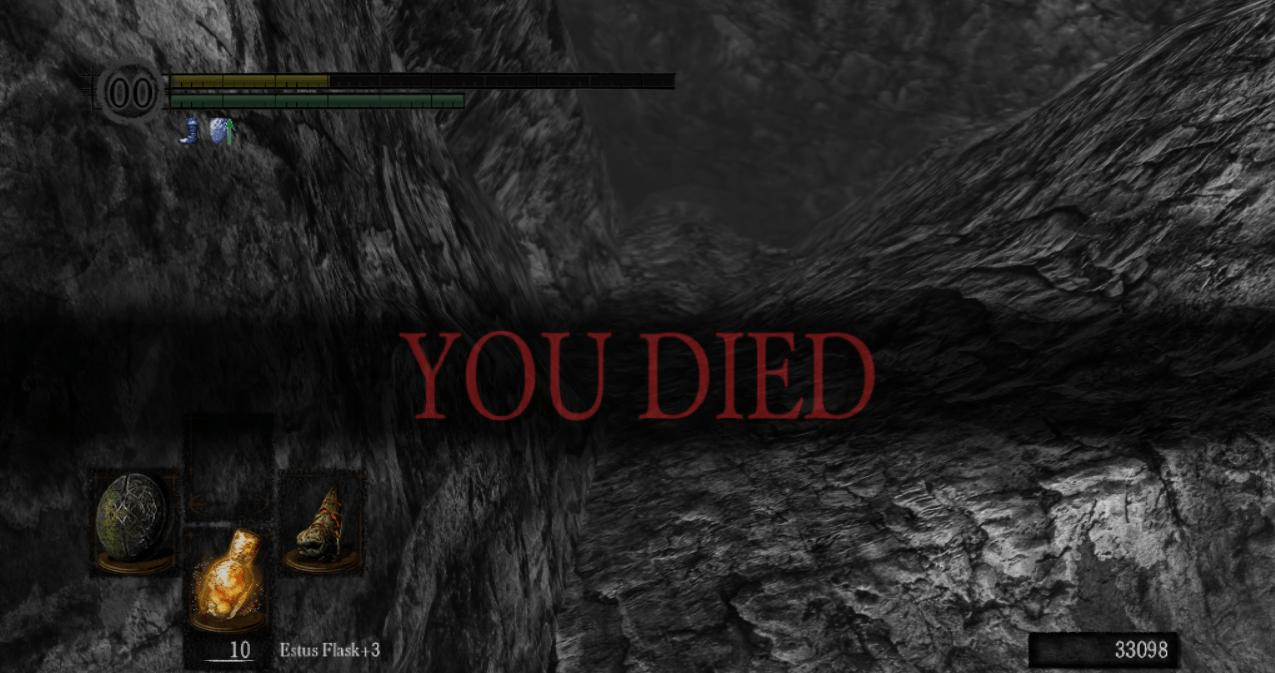

The Death Screen in Dark Souls (Image Credit: Bandai Namco)

Fantasies, especially those in video games, are often empowering. They allow the reader or player to imagine themselves as a hero slaying a near-infinite landscape of vicious monsters by their skill and prowess alone. But. Dark Souls does not cast the player as an invincible warrior. Instead, the player-character is a much more precarious sort of knightly figure. This knight faces considerably more powerful adversaries, many of whom can—and do, very, very often—kill the character with a single blow. It can be maddening to play. It may sometimes seem unfair. But the game revels in its extreme difficulty. And in doing so, the game asks its players to confront their own vulnerability and fragility.

The game does not force you to play as a knight specifically. But the archetype of the quest is central to the game’s narrative—as are the concepts of responsibility and duty. Even the cover art for all three games places knighthood at the center of the game. The series highlights the frailty of the medieval knightly figure, rather than its invincibility. This has important consequences for our own perceptions of who, and what, knights really were. Knights are frequently, and odiously, deployed by white supremacists and the so-called “alt-right”; for them, knights are symbols of righteous invincibility. So that makes it even more important for us to examine how popular culture views the vulnerability of the knight.

Finding medieval influences in the Dark Souls series is not hard. The grim-dark fantasy game carries its medievalesque aesthetics on its sleeve. However, its focus on vulnerability resonates, perhaps unexpectedly, with the same sort of anxieties you can find in actual medieval romance adventure stories. This is what drew my attention to the series—how much it stands in stark contrast with more typical modern representations of knights and knighthood.

The Fire Fades

The Dark Souls series crafts worlds centered on vulnerability, fragility, and transience. The continued cycle of life in the world is linked to kindling and re-kindling a fire, a process that, by its very nature, is temporary. Many characters throughout in the game world remind the player, over and over; “the fire fades”.

Even the divine offers no protection from entropy in these games’ world. There is a pantheon of creator gods in the world of Dark Souls. But they have all faded, died, or been consumed. In the first Dark Souls game, your final fight is against the leader of a dying pantheon, Gwyn the Lord of Light. Gwyn has gone mad in a doomed attempt to keep his age of fire going just a little longer. In Dark Souls III, you emerge into the game from the literal ash of the dead—the same dead who failed to kindle the fire of the world previously.

All this serves to instill a profound sense of loneliness and isolation. Whether it is the imposing monsters you confront, or the very architecture of worlds you navigate, you are tiny in comparison to the world around you. You are told that the ruins of castles and cities you walk through were crafted long ago. All that remains of these cultures survives through scraps of dialogue and the occasional description of an item you can use.

As I navigated each of these games, I noticed something interesting in myself. The overwhelming feeling of vulnerability instilled in me a desire to care for the few characters that I came across that weren’t monsters. Some of these characters ultimately betray you. Some, perhaps understandably, are nihilistic about their lot in life. But others maintain a stalwart sense of optimism in the midst of their crumbling world. I found myself utterly charmed by the reoccurring figure of Siegmeyer of Catarina, a relentlessly upbeat, and somewhat oblivious, chivalric knight archetype dressed in bulbous onion-shaped armor. YouTube creator VaatiVydia, a specialist in Dark Souls lore and storytelling, has created a video about Siegmeyer, part of an aptly named series of character studies called “Prepare to Cry”. In this video, VaatiVydia deftly observes that the more the player works to rescue Siegmeyer, the quicker he loses faith in his own bravery, eventually going mad. Siegmeyer therefore presents us with an uncomfortable and compelling examination of knighthood, one that is precarious and ultimately undone by attempts to secure his body from harm. It manifests a psychology that struggles to see bravery outside of exposing the body to danger over and over again. Despite his tragic end, Siegmeyer’s optimism sets him apart from the other morose figures of the world. Siegmeyer’s upbeat demeanor even acts as a meme in his own right within the fans of the Dark Souls community where some have dubbed him the “Onionbro”.

“Quite honestly, I have run up flat against a wall. Or, a gate, I should say. The thing just won’t budge, no matter how long I wait. And, oh, have I waited! So here I sit, in quite a pickle.” -Siegmeyer of Catarina (Image Credit: Bandai Namco)

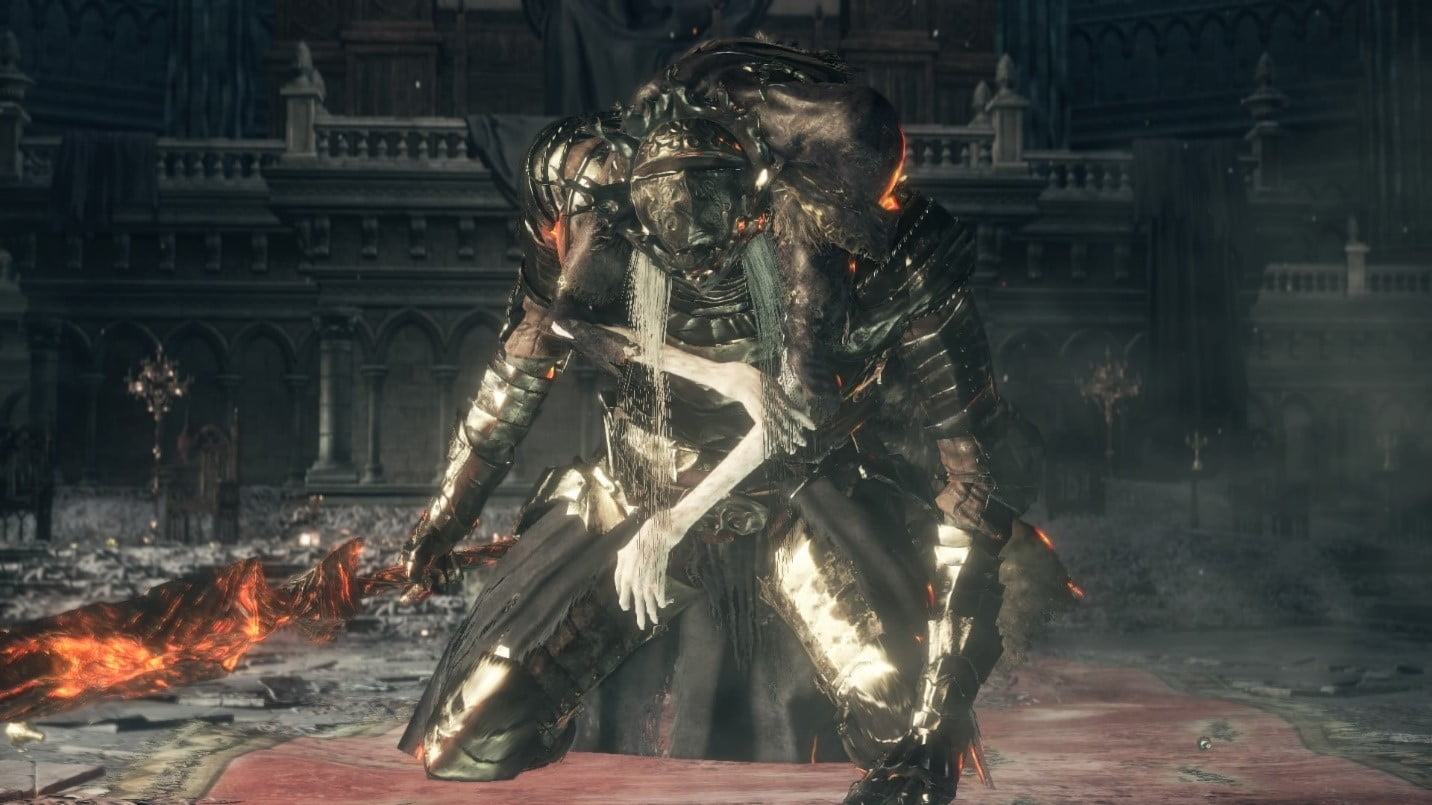

This pervasive sense of vulnerability can even evoke genuine sympathy with the enemies that you fight. This is perhaps best embodied in the Dark Souls III boss fight with the twin Princes Lorian and Lothric. Prince Lorian, the elder brother, fights on his knees. He is unable to use his legs after being cursed in a previous attempt to protect his younger brother Lothric. Lothric himself clings to his brother’s back during the fight; he is unable to stand on his own. These are bodies that have suffered in the world that you navigate. It is impossible to ignore how you both confront each other, even in combat, as exposed and fragile.

(Image Credit: Bandai Namco)

Prepare to Die

From a mechanical perspective, the player’s vulnerability is revealed through the game’s difficulty. The Dark Souls series, and indeed most games by the developer From Software, are punishing. They are known for it. The games require extreme patience and care. Mistakes can cause quick death—and, in some cases, can cost quite a lot of progress.

The violence of the game, therefore, instills a visceral sense of risk. The combat, simply put, has stakes. This is seen more often in the survival-horror genre of video games than the fantasy-action genre. Typically, fantasy video games attempt to instill in the player a sense of empowerment. There is progression within every Dark Souls game—the player’s character levels up and gets more powerful by acquiring new equipment and spells along the way. But it is always tempered by how precarious you remain—no matter how much you increase your stats. Every enemy, no matter how mundane looking, can pose a deadly threat to the character. No amount of armor can fully inure the player from damage. Often the protection afforded by equipment is minimal: enough to make a difference from time to time, but never enough to completely rely on for protection.

Appropriately enough, the tagline for first game in the series is “Prepare to Die”. The tagline has been taken up by many players as a clarion call to other, less-experienced players to toughen up and ‘git gud’ (a meme-ified way of simply saying “get good”) at the game. But it can also be read from another angle—one that asks you to be open to fragility and ready to learn from failure. The game will never let you stop being vulnerable. If you are to be successful as a player, you need to learn to embrace that vulnerability.

Shed Your Armor

These feelings of vulnerability resonate surprisingly well how the characters in medieval romances behave. Many familiar with the genre of medieval romance assume that the knights in these texts are paragons of martial prowess, nigh invincible in their skill with sword and lance. And this is often true. For example, in the Song of Roland, the companions Roland, Oliver, and Archbishop Turpin fight against impossible odds as the rearguard for Charlemagne’s army, slaying a truly bewildering number of enemy soldiers before eventually being overwhelmed. It really is the stuff of video games. Similarly, in many of the Arthurian romances, Galahad is considered the pinnacle of Arthurian knights: he is unconquerable in combat, unshakable in his piety, and incorruptible. However, knights like Roland and Galahad sometimes overshadow the nuanced ways in which the ideal of knighthood is expressed in many other medieval romance stories.

For example, in the Middle English romance Havelok the Dane the young protagonist Havelok spends his life acutely aware of the vulnerability of his body. He is imprisoned at an early age. He bears witness to the brutal murder of his sisters. He is threatened with drowning in the sea, raised as a scullion in exile, and eventually, and rather reluctantly, returns as a conquering warrior reclaiming his inheritance. While Havelok does indeed eventually win the day, but his path is underscored with how open his body is to harm from others.

Havelok only succeeds

based on those who surround him and support him, despite how vulnerable the

text makes him out to be. For instance, when Havelok returns to his native

Denmark in order to gain support for his claim to the throne he is awakened at

night by the court kissing his feet as a pledge of loyalty to him.

They fell quickly at his feet

They all greeted him

They were all overcome with joy

As if he had arisen from the grave.

They kissed his feet a hundred times

The toes, the nails, and the tips

So that be began to wake up

And became pale before them

For he thought they wished to kill him,

Or else imprison him and hurt him.

He fellen sone at hise fet.

(Havelok the Dane, verses 2158-2167).

Was non of hem that he ne gret –

Of joye he weren alle so fawen

So he him haveden of erthe drawen.

Hise fet he kisten an hundred sythes –

The tos, the nayles, and the lithes –

So that he bigan to wakne

And wit hem ful sore to blakne,

For he wende he wolden him slo,

Or elles binde him and do wo.

Instead of his community binding itself to him after some daring feat of arms, they do so—albeit in a pretty bizarre way—when he is at his most vulnerable.

Bevis of Hampton, another Middle English romance, also explores the vulnerability of its protagonist as a fundamental part of his knighthood. Bevis is at his most fragile when he is alone, absent of those who support him. Far from the invincible lone knight, Bevis draws strength from a community. After being imprisoned for seven years, Bevis is weak from hunger. Falling from his horse, Bevis claims he would give up his title and horse for a bare scrap of food:

‘Alas’ said Bevis when he fell down,

‘I who had an earldom

And a good swift horse

That men called Arundel

Now I would give it all up

For a sliver of bread!’

‘Allas!’ queth Beves, whan he doun cam,

(Bevis of Hampton 1821-1826).

‘Whilom ichadde an erldam

And an hors gode and snel,

That men clepede Arondel;

Now ich wolde yeve hit kof

For a schiver of a lof!’

Shortly after this embarrassing pratfall, Bevis fights a giant. Bevis is wounded—understandable given his weakened state:

And then he threw a spear at him,

He hit Bevis on the shoulder shedding

blood that ran down to Bevis’s feet,

When Bevis saw his own blood,

He went out of his mind

And he quickly ran at the giant

And proved he was a doughty man,

He smote him down to the neck bone:

And the giant fell to the ground.(Bevis of Hampton 1912-1920).

Anon he drough to him a dart,

Thourgh Beves scholder he hit schet,

The blod ran doun to Beves fet,

Tho Beves segh is owene blod,

Out of is wit he wex negh wod,

Unto the geaunt ful swithe he ran

And kedde that he was doughti man,

And smot ato his nekke bon:

The geaunt fel to grounde anon.

However, even in this victory, Bevis deviates from what we imagine a knightly paragon would do. He is enraged at the sight of his own blood, overwhelmed with emotion when his body is shown to be weaker than he expects. Anger and fragility consume Bevis—a far cry from the expectations of the knight and shining armor. Where he should be restrained and calm, Bevis is rash and furious.

Within these romances, these imperfect and fragile knights are just as important as their more well-known flawless and mighty counterparts. They provide more relatable characters to their readers and a more-varied array of stories and literary tropes. For every Roland or Galahad, there is a Havelok or Bevis; these vulnerable knights form a great and largely untapped source of material for games and other media.

Kindle the Flame

I read the Dark Souls series as an inheritor of the medieval conception of how knighthood and vulnerability intersect. To me, these games underscore the value of connection and community within imaginative spaces and ask the player to confront how bodies share fragility to one another rather than imagine their invulnerability. Knights are far from invincible conquerors. Knights are fragile.

Looking at the fragility of knights runs counter to contemporary misappropriation of knighthood by white supremacists and the fascist so-called alt-right. For them, knights represent a symbolic, and sometimes literal, force that shores up perceived vulnerabilities, rather than acknowledging them. The moniker “white knights” has frequently appeared as a within cadet branches of organizations like the Klu Klux Klan and other hate groups. For instance, the “Fraternal Order of Alt-Knights”, founded as the paramilitary arm of the “Proud Boys”, dress in armor looking to go into battle against Antifa activists during protests. The “Alt-Knight” crest reimagines them as modern-day crusaders, emblazoned with the battle-cry “Deus Vult” (God wills it). The symbolic knight for these groups is a part of a fantasy that ‘white identity’ and European culture is being overrun and besieged, and that the only defense of these ideas is by deploying knights to shore up that weakness. It’s a ridiculous, toxic appropriation of a medieval practice.

Expansive interpretations of knighthood, as seen in the Dark Souls series, help challenge the idea that knights draw their symbolic strength from wrapping themselves in armor and insulating themselves from others. It is maybe unsurprising that this toxic idea of knighthood is also the fantasy used by those who believe that communities gain strength when they are isolated from other cultures, races, and perspectives.

Small bonfires in the Dark Souls series act as symbol of progress for the player, a small bastion of safety amidst the challenges of the game world. They replenish your ability to heal yourself and resting at a one gives you a checkpoint if you die, returning you to the last one you rested at. Thematically, these small fires tie into the series larger questions of renewing the flames that keep the light of the world intact. While the role of the fire in the Dark Souls series is ambiguous at best, the bonfires might give us a chance to consider what is worth preserving and maintaining. We have opportunities to kindle our awareness to the vulnerabilities we share with others around us, to renew it, and preserve it. And this task is made all the more rewarding, perhaps, because it is so difficult.