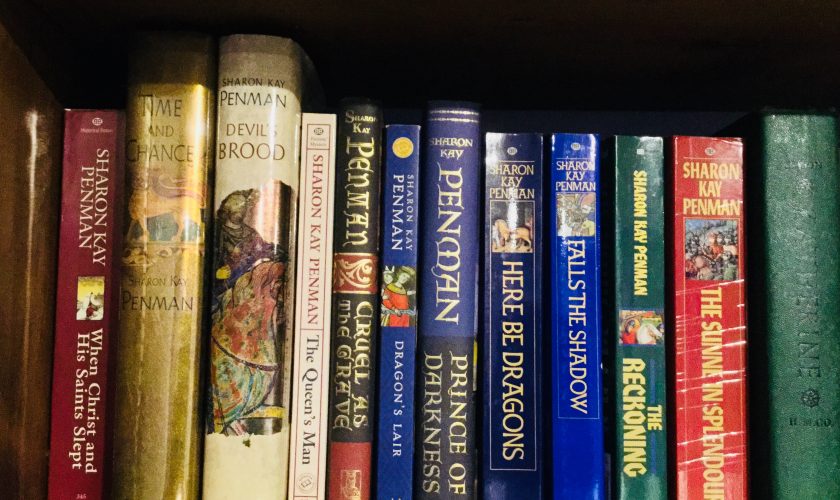

There are two books that I point to for the trajectory of my academic career. Both are works of historical fiction. Only one of them is actually good. The first is Jean Plaidy’s 1990 novel The Reluctant Queen, which I stumbled upon at age 12. The book itself was fine; the characters intrigued me enough that, when I was back home in Columbus, I looked up “Wars of the Roses fiction” at the library. I borrowed the first item that came up, a nine-hundred page onionskin paperback by Sharon Kay Penman titled The Sunne in Splendour.

Reader, I could not put it down.

I was consumed by this story, and by the history that inspired it. I read every book my local library had about the Wars of the Roses. My poor 9th grade history teacher had to read a ten-page screed about How Richard III Was Wronged, and my AP English teacher got fifteen pages about how Shakespeare also did Richard III dirty (but, in fairness, at least Shakespeare’s Richard is entertaining). Eventually, after many years, I wrote my PhD thesis, an academic book, and multiple articles, on influential women during the Wars of the Roses. I’m currently working on a biography of Elizabeth Woodville, who was married to Richard’s brother King Edward IV and who features as an antagonist in The Sunne in Splendour. My interest in the Wars of the Roses is also how I started reading George R.R. Martin in college, and found myself waiting in perpetuity for Godot The Winds of Winter and waxing academical about Game of Thrones. Which is to say, all of this is Sharon Penman’s fault.

In the chaos of the past year, I didn’t realize her new book, The Land Beyond the Sea, had come out. I’m both looking forward to reading it and dreading it, since I now know that there won’t be any others.

In January 2021, she passed away from pneumonia.

A Great Public Medievalist

Sharon Penman’s work stands as one of the great pillars of medieval historical fiction writing.

Penman wrote her first novel, The Sunne in Splendour, as her entry into the centuries-long dispute over the character of King Richard III of England. Meticulously researched and written over a period of 20 years while Penman was working as a tax attorney, it was published in 1982 to positive reviews. She then wrote a trilogy focusing on the struggles for Welsh independence in the 13th and 14th centuries (featuring one of the best interpretations I’ve seen of King John, a monarch perhaps best known as a skinny lion with mommy issues), as well as a series of novels chronicling the high drama of the 12th century English civil wars and the equally dramatic reigns of King Henry II and King Richard I. As though all of those—each clocking in between 700 and 1000 pages—weren’t enough, she also wrote a series of detective novels set in the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

I’ve reread The Sunne in Splendour easily a dozen times since that first time. There are passages I know off by heart. I’ve reread it enough that I have found things I don’t agree with in her research. It errs a bit too much on the side of Richard III being innocent. But I can’t argue with her character building: Penman’s depiction of the immediate supporting cast, especially Richard’s two brothers, is second to none. There are also the parts that still—even after a dozen re-reads—make me laugh out loud, shriek incoherently, or hit me like a gut punch.

Simon de Montfort is one of the total bastards of medieval history; not every author could make me feel things for Simon (other than “you need to die in a fire”). But Penman did. She had an incredible gift for world building and characterization, and knowing just when to twist the knife to keep you reading.

Her novels are a joy. But, like all authors, she had critics. The people who don’t like her books complain that she has tics, jokes, and character notes that she returns to over and over. But that never bothered me. Show me a famous male film director and I’ll show you tics, jokes, and character notes that reappear—they become an “auteur’s style”, not cause for criticism.

A Powerful Writer and Transparent Researcher

And as an academic medievalist, I continue to be awed by the thoroughness of her research, and her transparency about it. I loved the author notes that appeared at the end of every one of Penman’s novels. In them, she would address her research, the sources she’d found, and where she deviated from those sources. Sometimes it was as simple as changing a character’s location; in others, it was choosing one historical interpretation over another. This has been especially pronounced in her most recent books, as she delved into the thorny politics of the Second and Third Crusades, trying to take into account perspectives from as many sides as possible.

Penman did it because she cared about what her readers would take away from her books and strove to be as close as possible to the historical record. She was always willing to own up to errors, and even kept a list of “medieval mishaps” on her website, cataloguing the mistakes she’d found in her books after publication. Plenty of authors make mistakes; very few of them are willing to not just accept those mistakes but publicly address them and laugh at themselves a little. Following in her footsteps, I always include author notes when I write fiction.

Though she is gone, she has left behind a monumental body of work and legions of fans, who will remember not just her fantastic writing and excellent research, but her mentorship, kindness, and compassion. She was genuinely kind and had a wonderful relationship with her fans, including taking some with her on research trips. I am truly, truly sorry that I never got to meet her, or let her know how much her writing meant to me. That seems like the best one can hope for as a writer.

RIP, Sharon Kay Penman. Though she wrote fiction, she is one of the great medievalists of all time.