A couple of weeks ago, surrounded by pizza boxes and Game of Thrones-themed Oreos, my medieval literature students and I held our breath as Brienne of Tarth became a knight in name as she has always been in deed.

For both of you out there reading this who don’t watch Game of Thrones, Brienne has always been an example of valor for all Westerosi knights to follow. We first met her when she defeated Ser Loras Tyrell in a tournament, and, as her reward, asked only to be made a member of the Kingsguard. She continued to serve her sworn liege lady, Catelyn Stark, long after Catelyn was murdered with most of her family at the infamous Red Wedding. She fought to protect Lady Stark’s daughters, Sansa and Arya, even when they rejected her aid. She avenged the murder of her king, Renly Baratheon, even though no one was present to see this justice served. She even fought off a massive bear with nothing but a wooden sword! Brienne shows her viewers—especially the legions for whom she serves as a standard-bearer for female empowerment—what a woman can do.

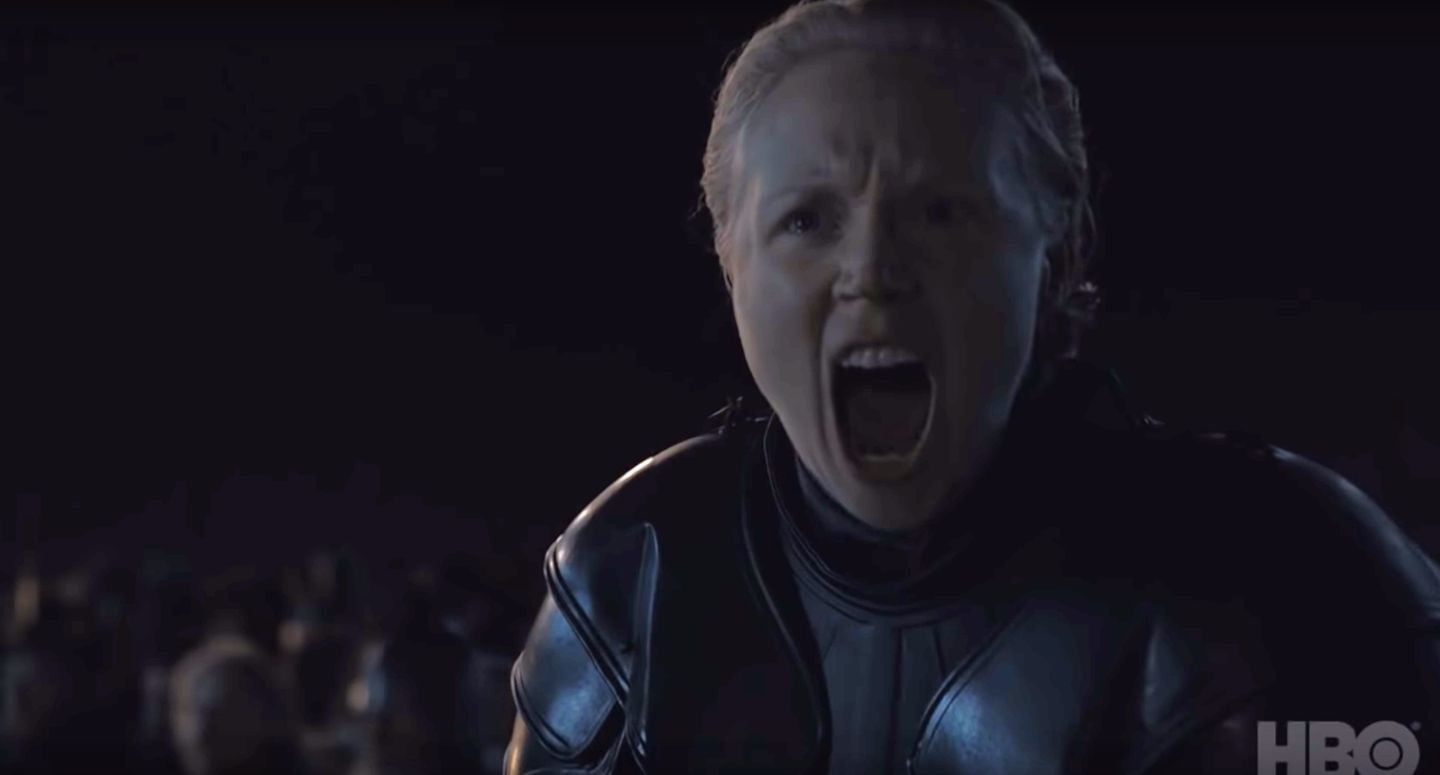

When Ser Brienne’s eyes glistened with pride at finally becoming a Knight of the Seven Kingdoms in Season 8 Episode 2, I felt that singular euphoria experienced by all women who have watched their personal heroine get the recognition she deserves. It was exhilarating.

Brienne’s prowess reminds me of Penthesilea, the militant woman who defends Troy in Greek mythology and, later, in medieval tales like Christine de Pizan’s City of Ladies, John Lydgate’s Troy Book, and, my personal favorite, Benoît de Sainte-Maure’s Romance of Troy. By fighting bravely and acting with honor, Brienne and Penthesilea both embody ideal knighthood. Yet despite their obvious prowess, neither Brienne nor Penthesilea fits in on the battlefield.

When Penthesilea’s golden tendrils escape her helmet and cascade down her armored back in Benoît’s romance, they signal to her Greek opponents that she does not belong to the military brotherhood that unifies the rest of their adversaries. Instead, Penthesilea leads hordes of Amazons—mythical female warriors inspired by the mounted tribes of Scythia and Sarmatia (in Central Eurasia, especially present day Ukraine) and armed by Benoît with the weapons and techniques of medieval knights. When Penthesilea and the Amazons arrive on horseback to defend Troy, their audacious female knighthood makes them the primary target of the Greeks.

Likewise, Brienne is well-schooled in the rituals of knighthood even though those same rituals exclude her on the basis of her gender. In Season 8 Episode 2, she initially dismissed the suggestion of her own knighting, blaming “tradition” for the fact that “women can’t be knights.” We watched, enraptured, as Jaime Lannister knighted her anyway.

We relished Brienne’s newfound knighthood even as an army of the dead formed ranks before launching its assault on Winterfell. Perhaps there was hope?

Yet if Penthesilea and her mythical Amazons have taught us anything, it is that all is not possible for the women who fight and die with men. For Benoît’s Penthesilea, fighting the Greeks spells doom: the Greek soldier Pyrrhus cleaves her arm from her body, drags her from her horse, smashes her skull, and dismembers her while her Amazons watch in horror. Pyrrhus answers Penthesilea’s audacity with the most brutal death of medieval romance in any language in an attempt to purge her from the masculine rites of war.

Still, despite its horrifying finality, death does not conclude Penthesilea’s story.

The Greeks refuse Penthesilea an honorable burial, instead throwing the pieces of her body in the Scamander River. Yet this is not the end.

Her allies gather her body from the riverbanks and bury her with honor. Even this is not the end.

Her story concludes with songs that praise her accomplishments as a knight, in a legacy that echoes across the ages.

Such a death is not an end. It is not, as Samwell Tarly proposes in the same episode, while the allied Westerosi prepare for the Battle of Winterfell, “forgetting, being forgotten.” Heroic death is defined by the myths it engenders, the tales that preserve lives of honor for generations to come.

My students revel in the valor, transmitted across the centuries, of women who flouted expectations of their gender. They do not immerse themselves in the study of medieval legends just to analyze Game of Thrones, fruitful as the comparisons may be. They pore over the heroines of the past to learn what it means to be a leader. They find inspiration in women who demanded the respect they knew they deserved and kept their vows even when it cost them their lives.

Last Sunday, when my students and I gathered again to watch the next episode, we felt sure we would witness the death of Brienne. We put aside grading, exams, and final papers to watch a woman we admire die for what she believes—to learn how Ser Brienne of Tarth would be remembered.

Yet, she did not die! We watched, spellbound, as she fought with honor alongside other brave women and men. We cheered together as she emerged victorious.

This week, in Season 8 Episode 4, Brienne stood alongside the grim-faced survivors of the Battle of Winterfell to commemorate the dead. With the pyres lit, Brienne shared in the celebrations of survival denied to Penthesilea: she drank with her comrades in arms and slept with Jamie Lannister, the man she loves; she called him to act with honor and, when he refused, she wept in despair.

Brienne is not, like Penthesilea, a tertiary character brutally sacrificed to build viewer sympathy by illustrating the ignominy of her opponents. Brienne does not exist merely to facilitate the progression of her narrative or anyone else’s.

Brienne dominates this final season of Game of Thrones. Depicted in the fullness of her humanity, Brienne’s emotional depth is matched only by her moral rectitude. Brienne is a heroine for our age, a testament to a generation demanding that women’s stories be told with passion and complexity.

This generation insists that our heroines no longer be punished for their audacity. This generation clamors to celebrate rather than condemn women’s excellence. A hunger for heroines is driving change in our society and forging paths for women—in all the imperfection and humanity that we now claim as our own, just as male leaders have for millennia—to take the reins.

Now that is exhilarating.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.