Part XXXIV in our ongoing series on Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, by Amy S. Kaufman. You can find the rest of the special series here.

Medieval historians are deeply frustrated by white supremacist appropriation of the Middle Ages. In the face of an alarming rise in hate speech and violent acts that rely on medieval memes, medievalists have risen up to reclaim the past from racists in popular media, in their classrooms, and even in the academy.

But although the symbols embraced by the far right may seem medieval—from Ku Klux Klan titles like “Grand Dragon” to the pseudo-medieval shields carried by “alt-righters”—their version of the Middle Ages is often filtered through contemporary medievalism in film, television, fantasy fiction, and video games. Medievalism is different from an interest in medieval history: it’s the appropriation, and often revision, of the medieval past. Thus, scholars may be pushing back with facts, but medievalism’s practitioners are more likely to get their “history” from Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings.

It’s easy to dismiss the random nature of white supremacist symbolism as ahistorical, lazy, or ignorant: after all they’re wearing polo shirts and carrying medieval heraldry in defense of Robert E. Lee and the First Amendment. (Wasn’t America supposed to be all about throwing off the royal European yoke?). But medievalism’s real currency is myth, not history. The men who shout “You will not replace us!” (and the anti-Semitic variant, “Jews will not replace us!”) brandish shields and medieval banners in American streets because medievalism has long soothed white male anxieties about their place in the world.

Today’s American far right is, in fact, carrying on a long historical tradition by embracing medievalism, just not the one that they think. Instead of replicating the Middle Ages, they’re replicating the medievalism of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Chivalric Fantasies

We often imagine that racial progress in America has been linear, improving in an unbroken upward trajectory ever since Emancipation. But that simply isn’t true. The KKK itself was founded to roll back racial progress, and for many years, it was disturbingly effective.

The first incarnation of the Klan formed just after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction period in which Congress attempted to give former slaves civil rights. In fact, when the original Ku Klux Klan first donned their hoods, over 2000 black men held political office. Women’s rights groups also became a formidable force in the nineteenth century, as women campaigned for suffrage and equality. Suddenly, white men who believed they had been born atop a hierarchical ladder of race and gender found themselves competing with black men in the workplace and politics, and having their authority challenged at home.

For such men, the myth of a white, patriarchal Middle Ages became a fantasy and a refuge. Southern men nursed on the chivalric tales of Sir Walter Scott and William Morris yearned to imagine themselves as knights and heroes. They believed their medieval “heritage” had been stolen from them by those agitating for civil rights and women’s rights, and they were determined to get their power back.

The Klan deployed violent terrorism, political maneuvering, and a cloak of “heroic” medievalism in its attempt to restore white supremacy to the South. Calling themselves “The Invisible Empire,” they considered themselves knights but dressed as ghosts to terrorize black citizens. Congress eventually passed laws to limit the Klan’s violence, and infighting led to disorganization, both of which contributed to the first Klan’s decline. But as the Southern Poverty Law Center explains,

The laws probably dampened the enthusiasm for the Ku Klux Klan, but they can hardly be credited with destroying the hooded order. By the mid-1870s, white Southerners didn’t need the Klan as much as before because they had by that time retaken control of most Southern state governments.

As Reconstruction came to an end, civil rights were snatched away through successive waves of voter suppression, intimidation, poll taxes, and Jim Crow laws. The first Klan didn’t go underground so much as it went mainstream: when they succeeded at seizing power, there was no need to hide behind their hoods.

Most people are more familiar with the Klan’s second incarnation, which formed in the same early-twentieth-century white backlash that gave rise to America’s Confederate statues and monuments. Like the statues, the second Klan sprang into being based on myth rather than history: primarily, nostalgia for the first KKK “knights,” which, according to southern legend, had slain the twin dragons of racial equality and Reconstruction.

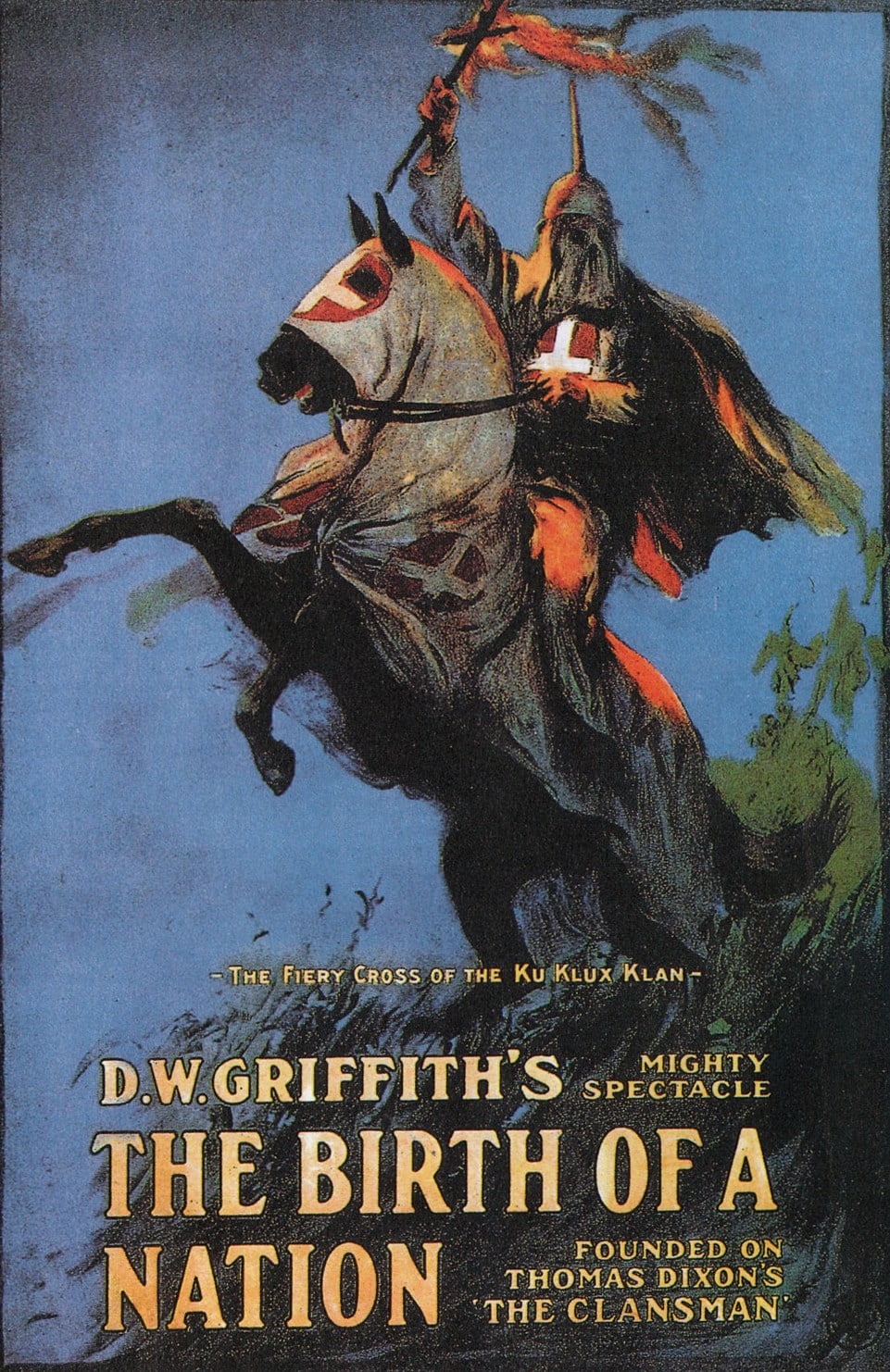

In 1905, novelist Thomas Dixon romanticized the terrorist actions of the first KKK as a story of “medieval” vengeance in his novel The Clansman. His book imagines Reconstruction as a kind of living hell for white people in which former slaves destroy the government, banks, and police force, driving the South into violent chaos. The last straw for the novel’s protagonist, Ben Cameron, is the rape of a young white woman by a freed slave.

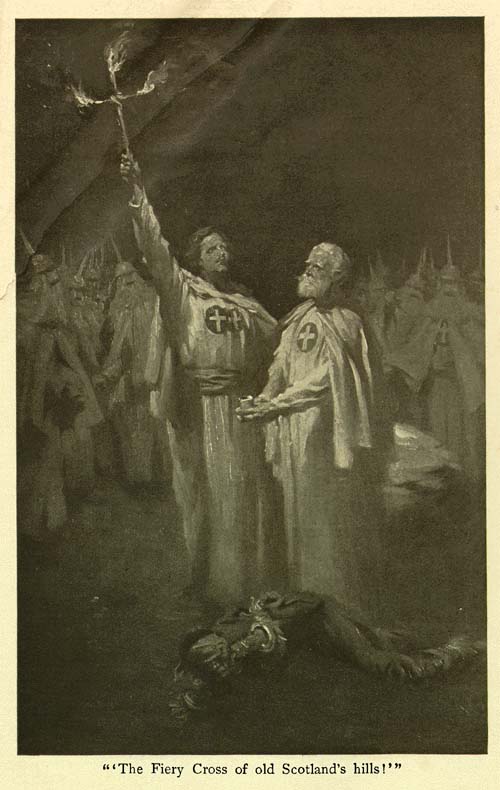

Cameron, who will become the Klan’s fictional first Grand Dragon, uses the young woman’s rape and her resulting suicide to mobilize his fellow white men into creating an “Institution of Chivalry” inspired by their ancestors, the knights of “Old Scotland,” for the sole purpose of protecting white women’s virtue:

In a land of light and beauty and love our women are prisoners of danger and fear. While the heathen walks his native heath unharmed and unafraid, in this fair Christian Southland our sisters, wives, and daughters dare not stroll at twilight through the streets or step beyond the highway at noon.

Dixon medievalizes many aspects of the KKK, including the burning cross that would be a hallmark of white terrorism in the twentieth century. He calls it “The Fiery Cross of old Scotland’s hills.” His narrator also drones on about his heroes’ knightly appearances and their supposed ancestry as the descendants of medieval Scots:

The moon was now shining brightly, and its light shimmering on the silent horses and men with their tall spiked caps made a picture such as the world had not seen since the Knights of the Middle Ages rode on their Holy Crusades.

For Dixon, his heroes’ made-up medieval birthright validates their superiority and right to rule. His Ku Klux Klan launches a bloody campaign of violence, intimidation, and murder to restore white supremacy to the South. Not only does Dixon’s fantasy KKK destroy civil rights, but it also wipes out that pesky feminist movement as the women in the novel learn they must submit to white Southern men for their own protection.

Homegrown American Terrorism

Dixon’s fantasy about the founding of the KKK might have faded into obscurity if it hadn’t been for D.W. Griffith, who turned The Clansman into a film that would shake the United States to its core: The Birth of a Nation. Thanks to Griffith’s influential connections—including President Woodrow Wilson, who had been friends with Dixon in college and screened The Birth of a Nation at the White House—Dixon’s dream of white masculinity run rampant went mainstream. And countless black American lives were sacrificed to his racist nostalgia.

The Birth of a Nation helped inspire the second Ku Klux Klan, which became both far more popular and more destructive than the first Klan. The second Klan committed decades of terrorism against black citizens. And by 1925, millions of Americans had joined the KKK.

The same nostalgic medievalism that drove Dixon’s novel also fueled the Klan’s recruiting power, from its regalia and heraldry to its rhetoric of white knighthood and faux chivalry.

The same nostalgic medievalism that drove Dixon’s novel also fueled the Klan’s recruiting power, from its regalia and heraldry to its rhetoric of white knighthood and faux chivalry.

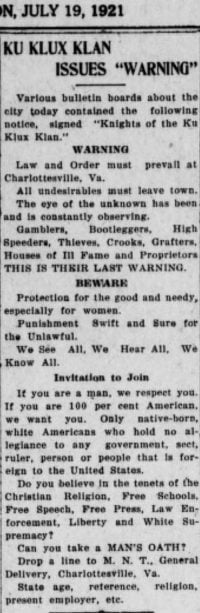

For example, in 1921, the Charlottesville Klan advertised (right) for members by asking potential “knights”: “Can you take a MAN’S OATH?” An unpleasant preview of today’s white supremacist talking points, the ad calls for “law and order” and promises “protection for the good and needy, especially for women,” while announcing that the KKK is specifically seeking “native-born white Americans” who believe in “Christian religion,” “Free Speech,” “Liberty,” and “White Supremacy.”

The myth of white female frailty and white male chivalry not only obscured rampant existing white violence against black women, but neomedieval fantasies about protecting white female bodies also led to a new epidemic of violence against black Americans. Whites with delusions of heroism formed lynch mobs in Omaha, Nebraska, massacred families in Rosewood, Florida, and decimated an entire black business district in Tulsa, among many, many other tragedies. And this twisted “chivalric” white male anxiety over white female bodies is far from ancient history: in 2015, Dylann Roof declared, “You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. You have to go,” just before he murdered the black Americans who had welcomed him into their Wednesday night Bible study.

A Medievalism of Her Own

Although the second KKK relied on the myth that they were “protecting” white women to motivate its members, plenty of white women were complicit in Klan violence. The “Women of the Ku Klux Klan,” which formed just after white women won suffrage, had, at one point, over half a million members. Groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy supported the Klan and sponsored the very Confederate monuments we’re still fighting about today. Their publication, The Southern Magazine, published screeds that called the Ku Klux Klan “the bravest and best men of the South” and tried to justify Klan violence as the protection of white womanhood:

The South was in the clutches of a veritable “Black Death,” for every morn, it seemed, brought news of another outrage upon white womanhood… What would you have done, men of the North? Would you have arisen, in spite of laws, in spite of Federal troops, in spite of impending imprisonment and possible death, in defense of a mother, a sister, a wife or a sweetheart? There can be but one answer, for manhood still lives, the blood is red, and the hearts are pure.

Racist white ladies also enjoyed imagining themselves as medieval warrior-women. The WKKK adopted Klan names and regalia for their own rituals and drew on medieval women like Joan of Arc for inspiration. In fact, the tradition continues to this day: as a recent exposé by Seward Darby reveals, the women of today’s new “alt-right” movement imagine themselves as “lionesses and shield maidens and Valkyries” who can “inspire men to fight political battles for the future of white civilization.”

FOAK This

Today, the Southern Poverty Law Center is tracking American hate groups with names like “Wolves of Vinland,” “Rebel Brigade Knights of the True Invisible Empire,” and “The Holy Nation of Odin” alongside the unfortunately enduring “Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.” The Proud Boys, one of the alt-right groups that invaded the liberal bastion of Berkeley, California this spring, even formed its own pseudo-medieval militia: they call it “The Fraternal Order of Alt Knights” (FOAK).

No one who studies the history of medievalism will be surprised that an oversimplified, Eurocentric, patriarchal Middle Ages comforts men who are terrified of being “replaced.” In their fantasy world, they can pretend to be brothers, knights, and heroes serving a higher purpose. But their real battle is against reality.

The white supremacists who pretend to be knights crusading in defense of American history get both medieval history and American history wrong for a reason: because facing the truth means admitting that they are not different or special, not the chosen descendants of a past full of heroism and glory. It means facing the fact that they’re not carrying on noble, chivalric traditions, but are instead spreading the murderous revisionist history of monsters.

That might be a hard truth for them to swallow, but it’s one the rest of us have had to suffer under for far too long.

Further Reading

Susan Aronstein, Hollywood Knights: Arthurian Cinema and the Politics of Nostalgia, Palgrave, 2005.

Kelly J. Baker, The Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930, University Press of Kansas, 2011.

Tison Pugh, Queer Chivalry: The Myth of White Masculinity in Southern Literature, University of Virginia Press, 2013.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And click to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.

Comments are closed.