One of the most venerable genres of computer games is the city-building simulator. SimCity is the great-granddaddy of them all, of course, and many kids in my generation wasted plenty of recess hours hunched over a computer program which, somehow, managed to make urban planning and civic zoning fun.

SimCity’s breakout success made its makers at Maxis a household name among many gamers. And Maxis went on to launch a number of sequels (though the shambolic failure of the most recent iteration has threatened to derail its future), as well as a number of other Sim-games (SimEarth, SimLife, SimAnt, SimFarm). Other companies also took up the mantle, often asking their players to build cities in exciting historical locales: Pharaoh for ancient Egypt, Caesar for Rome, Tropico for the 20th-century Caribbean, and the Anno series had titles set in 1701, 1404 and 2070.

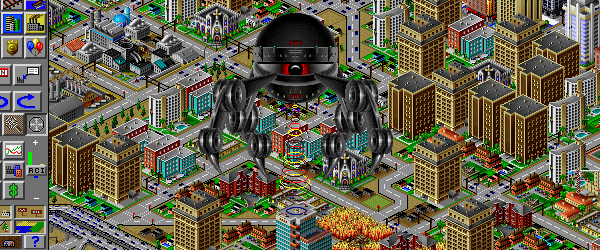

The remarkable thing about the gameplay of SimCity was its lack of external conflict. In short, by contrast with the vast majority of games then and now, there were no bad guys to shoot, no race cars to overtake, no bosses to defeat, no princesses to save. The fundamental challenge was in creating a perfectly-balanced system, where each of the metaphorical gears would run in time with all the others. That is, until this guy showed up to ruin everything:

By contrast, city-Sims set in the Middle Ages typically restored the external conflict. Medieval cities, it seems, were less interesting as whirring, dynamic urban centers, and more interesting as fortifications against plundering hordes. The successful Stronghold franchise is a testament to this trend, where, in only the medieval context, the city-sim was replaced by the castle-sim.

And so it was no small interest that I recently began playing Banished.

Banished: Raise tiny medieval people, and watch them starve.

Banished was released in February of 2014 by a one-man game studio. It was quickly heralded by many game critics as a return-to-form for the city-building genre, where the player is simply asked to build a medieval village. This village consists not of millions of people but, instead, tens, or—after many successful hours playing—perhaps a few hundred.

The conflict and challenge at the core of the game is a refreshing one for me as a medievalist. Instead of repelling hordes of invaders, all the game asks you to do is survive the winter.

Doing this, much to my surprise and horror, can be shockingly difficult. Everything was going well in my little fictional village of Innesburg; I’d built houses for all of the families, had a few crop fields and a fishing dock built, and was even considering building a quarry for a more reliable source of stone.

And then the crop failure hit. The winter came early, the fruit withered on the vine. Red warnings flashed. And then the messages:

Heide the Farmer has died of starvation.

Ulfgar the Labourer has died of starvation.

Knorr the Child has died of starvation.

Ever since the explosion of medievalism in the late 19th century, there has been a romanticization of medieval agrarian life. It lives on to this day; there remains a pervasive sense that the medieval countryside was an idyll. Without interfering technology, medieval humanity lived in cooperation with nature rather than in conflict with it. People ate with the seasons and did honest labour with their hands. William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement catapulted this idea into the popular imagination, which remains echoing through our culture today with the neo-homecrafts, homestead living, grow-your-own and organic food movements.

But Banished provides a stark reminder for those romantics: living with the seasons really sucks. Sure, growing and eating your own peas and squash can be incredibly rewarding; more people should do it. But relying on them to survive can cause hardship and horror that are, thankfully, rare in the western world today. And the value of this game was that, watching these little people die offered me just a little taste of the same fear, frustration, desperation, shock and resignation which might have been felt by those who suffered through the Great Famine of 1315-17, or who resorted to the most desperate measures possible during the “starving time” at the Jamestown colony in 1609-10, when 440 of the 500 colonists died.

But my little electronic village lived on. But as I chose a new crop to sow in the springtime (since wheat clearly wasn’t the most reliable…), I noticed something strange:

Pumpkins.

Pumpkins are a new-world crop, and thus, implicitly, not medieval. So are potatoes, corn, and squash—all options in the game. Perhaps the designer simply didn’t know this, but I began to look further. Zooming very close to my little e-people, their little outfits were decidedly not medieval. The ladies all wore skirts, the men all wore slacks, shirts and waistcoats. And the architecture too—the little houses, the little church, the little school: not medieval.

Taken in sum total, the design of the game looks roughly 18th-century, probably somewhere in colonial America (or Canada, considering the weather).

But why had I thought it was medieval in the first place?

I searched through the game’s website; they never use the word, nor do they make any mention of what place or period the game is set. Neither in the game itself, nor in the game’s documentation and wiki, nor its press releases or advertising.

So where had I gotten the notion it was medieval?

The media.

Specifically, every reputable games website that discussed or reviewed the game called it medieval. Every single one. PC Gamer. The Escapist. Rock Paper Shotgun. EuroGamer. Indie Statik. Hardcore Gamer; the list goes on. Each of them, either in their articles or in their headlines call the game medieval.

… But so what?

But what does that matter? Revealing this seems like little more than a historian engaging in a bit of self-indulgent “gotcha” journalism on people who never claim to experts on the medieval past.

The reason why this pervasive misidentification of the game is important is that it can grant us a window into how the public understands, instinctively and implicitly, what ‘medieval’ means, and what ‘the Middle Ages’ were.

So far as I am able to discern, there are a few features of Banished which lead it to be called ‘medieval’. Primarily, this is a game that centers on an agrarian society which is definitely pre-industrialization. All your e-people wield simple hand tools for their labours. All of the buildings are made of some combination of wood, stone, and iron: no brick to be seen, no concrete, no glass to speak of. The building roofs—which the player spends a lot of the game staring at—are either thatched or slate-tiled.

Additionally, the simulated economy, such as it is, is not a currency-based market economy. Within your little village, everyone sets about the task that the player assigns them with equal fervour, and the reward for their labour is to take a share of the centrally-collected goods (if there are any to be had). No rich, no poor: it is a Communist agrarian dream (or, if done poorly, a Stalinist agrarian nightmare). Trade with the outside world is done entirely in goods-for-goods. And there are no African slaves—or any non-white people for that matter.

And, as mentioned above, life in this little world can be brutal, nasty and short. While life has always been varying shades of terrible for the world’s poor, the only historical time period where this is marked as a specific feature of the era in the popular imagination is the Middle Ages.

So, while Banished is clearly set in a vaguely-colonial-American setting (or, provocatively, perhaps the world’s first Amish-sim), it is perhaps understandable that it might have been mis-identified as medieval.

Medieval = Agrarian = Medieval =…

The problem that this raises for historians is that there obviously is not a clear sense in the public consciousness of a distinction between different historical agrarian societies. Our sense of period is clearer when examining the lives of the wealthy and powerful—partially because they are who history has traditionally focused on (in large part due to documentary sources largely focusing on them), and partially because they had the wealth to purchase the newest fashions and latest trinkets. Agrarian lives may have changed less rapidly, but that certainly does not mean that they were static. Grouping every European and North-American agrarian society before the 20th-century under the same “medieval” schema does them all a disservice.

So, in sum, Banished is a great game that runs the risk of devouring a good quantity of your free time. But, despite what the games media thinks, it’s not medieval. But the fact that it is consistently mis-labeled as medieval is incredibly revelatory for all of us about what that word has come to mean.

Was your intention to make me want to play Banished?

No, but I’ll consider it a fringe benefit!

It strikes my as odd that people thought of this as medieval, being as idyllic as it is. As far as I can tell from my experience, most people think of the Middle Ages as being exactly the opposite of idyllic. Something among the lines of Monty Python’s Quest for the Holy Grail.

Usually I don’t comment online, but this article was very insightful. Media and popular beliefs can be very misleading if one is not aware. Thanks for sharing your specialist point of view.