Monday, 15 April 2019.

Filled with anguish for what happened to the majestic Notre Dame de Paris, I went to bed struggling to put my mind to sleep with scenes still popping up of the proud cathedral battling the desolating flames. I woke up the following day rubbing my eyes and grabbing my phone to check my email, as usual. There was a message with the title “Al Aqsa”. I hurriedly took to news outlets and social media to see what happened to the iconic mosque, and I was relieved to learn that the blaze there was quenched tout de suite. The fire, that was reportedly inadvertently started by a group of playful children (according to Palestinian Waqf officials), broke out quickly in the guardroom of the courtyard of al-Muṣallā al-Marwanī (the Marwānīd Prayer Hall), better known in the West as the Solomon’s Stables.

For many non-Muslims, this fire may have been the first time they had heard of the Aqṣā mosque, despite it being one of the holiest places in Islam. So, I thought this might be as good an opportunity as any to introduce the readers of The Public Medievalist to its storied past and offer a guided historical tour of this edifice that has survived fire, earthquakes, and even a few Crusaders in its time.

Why the Aqṣā is Important

The calibre of the Aqṣā mosque for Muslims is, in a way, comparable to that of the Notre Dame for Christians. The Aqṣā was their first qibla, (i.e. the direction Muslims faced when praying), before Makka and one of only three mosques to which Muslim are urged (by the Prophet) to travel to do prayer. The other two are those of Makka and Madina:

“People shall journey to but three mosques, al-Masjid Ḥarām [at Makka], my mosque [at Madina], and the Aqṣā mosque [at Jerusalem]”

said the Prophet in one famous ḥadīth. The Arabic name, al-Masjid al-Aqṣā (the Farthest Mosque), is inspired by a Qurʾānic passage on the Night Journey (Qurʾān 17. 1) which celebrates the Prophet Muḥammad’s miraculous excursion from al-Masjid al-Ḥarām where he lived, to al-Masjid al-Aqṣā, and then up to the Heaven.

The Structure of the Aqṣā

The mosque itself, (i.e. the covered prayer space), constitutes only a part of a grander complex that also includes other structures, minarets, and memorials. It is known in the Muslim tradition, particularly starting from the Ottoman period, as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (the Noble Sanctum). Situated in the southern side of the ensemble, the silver-domed mosque still preserves very nearly the same features it has had since the time of its foundation. In the present day, the Muslim people use the term ‘Aqṣā mosque’ to refer to the whole complex and to the particular mosque interchangeably. More confusingly, some use the term to refer to the spectacular Umayyad Dome of the Rock that is also included in the complex. A better terminology uses ‘al-Masjid al-Aqṣā’ to refer to the whole ensemble and ‘al-Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā’ to refer to the mosque itself. The latter is also known as al-Masjid al-Qiblī (as it locates in the qibla side of the enclosure), al-Mughaṭṭā (the roofed part) and Masjid al-Jumuʿa (the Friday mosque).

The History of the Aqṣā

The first mosque here was reportedly put up by the caliph ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb when Jerusalem capitulated to him in 16/637 CE. While mentioned by a number of medieval Muslim chroniclers, the fullest description of that ‘first’ mosque is conveyed by Arculf, a Frankish bishop (Galliarum Episcopus) who made the pilgrimage to the Holy Land in around 59-62/679–82 CE:

In that famous place where the Temple once stood, near the [city] was on the east, the Saracens [note: an archaic Eurocentric appellation for Muslims] now frequent an oblong house of prayer which they pieced together with upright planks and large beams over some ruined remains. It is said that the building can hold up to three thousand people.

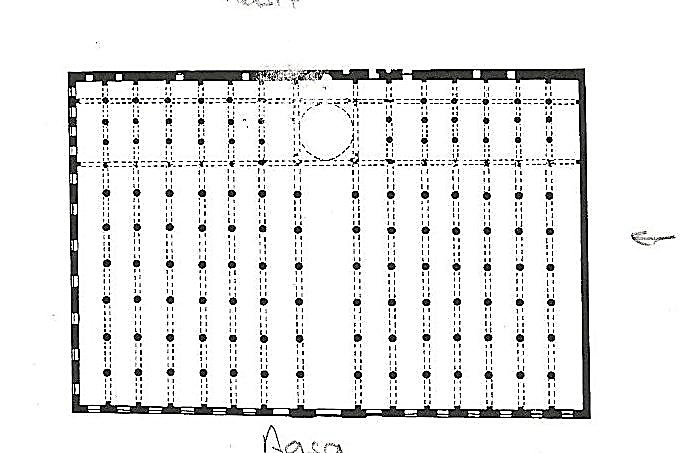

While this statement by Arculf is still seen by many as an acceptable account of the structure, some have recently argued that it is generally unreliable. A third group believe that the mosque he saw was founded by the founder of the Umayyad caliphate, Muʿāwiya b. Abī Sufyān and not ʿUmar, seeing that Arculf visited Jerusalem in the former’s reign. To the latter, however, they attribute an earlier mosque of a smaller capacity (suitable for 1000 worshippers). After the works of ʿUmar, the Aqṣā mosque was more certainly rebuilt in the Umayyad period. It was a rectangular structure composed of an axial nave that is surmounted by a high wooden dome sheathed with lead. The nave was flanked with vertical bays.

Due to inconclusive archaeological evidence, nevertheless, there are two theories on to whom the Umayyad Aqṣā should be attributed. According to a majority of early historians and geographers, the mosque was built by the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān in ca. 65/685 CE. Others believe it is due to his son and successor al-Walīd. Based on a more systematic analysis of all the evidence available (i.e. archaeology, papyrology and Muslim as well as non-Muslim early sources), a majority of scholars now come to believe that the Marwānīd construction of the Aqṣā mosque was first commissioned by ʿAbd al-Malik and completed by his son al-Walīd in 87/706.

In its many years, the structure has been through a lot. The Umayyad Aqṣā mosque was later struck by an earthquake that destroyed the domed mughaṭṭā towards the end of the Umayyad period in 128/746. It was thus reconstructed in the ʿAbbāsid period by the caliph Abū Jaʿfar al-Manṣūr in 136/754 CE. The only surviving remnants from the Umayyad structure are the arches, which are supported on squat marble columns with stiff Byzantine foliage situated to either sides of the cupola near the entrance. Some also attribute the lower part of the present walls of the main aisle to ʿAbd al-Malik’s time. In 163/780 CE, the mosque had to be rebuilt again, this time by al-Manṣūr’s son and successor al-Mahdī, after being struck by another earthquake. In 424/1033 CE, al-Mahdī’s mosque was largely destroyed by a third earthquake and thus rebuilt by the Fāṭmid caliph al-Ẓāhir li-Iʿzāz Dīn Allāh two years afterwards. Al-Ẓāhir’s architects reconstructed the dome of wood and sheeted it with lead enamelwork. That is the mosque that remains standing today. Today’s mosque retains the layout of the Fatimid structure as well as some of its decorative programme.

The Aqṣā and the Crusades

After Jerusalem was seized by the Crusaders in 492/1099 CE, the Aqṣā mosque was renamed ‘the Temple of Solomon’. The Dome of the Rock was converted into a church and rechristened ‘the Temple of God’ (Templum Domini). The mosque was first used as a royal palace, and then as the headquarters of the Templar Knights. During the Crusades, the architecture of the mosque was largely refashioned to better serve its new functions and many structures were added in the enclosure. Later in 583/1187 CE, these alterations were undone and the holy site regained its Islamic character when the first Ayyūbid sultan Ṣalāh al-Dīn recaptured the city. Subsequently, and thanks to its prestige in Muslim culture, the Aqṣā benefited from numerous amendments: it has been restored, refurbished, and refurnished by patrons from several different Muslim epochs: Ayyūbid, Māmlūk, Ottoman and modern. In 1969, the dome was rebuilt with concrete and plated with anodized aluminum; this was later redone with lead so as to better resemble its medieval Fāṭimid predecessor.

Into the Halls

Constituting the biggest covered space in the modern Aqṣā mosque (at 4500 m2), the Marwānīd Prayer Hall, where the fire broke out, comprises 16 riwāqs (arcades) made up of stone pillars. It is located beneath the south-eastern plazas of the Aqṣā mosque and can be reached through a stone staircase in the north-western part of the Qiblī mosque. Otherwise, it can be accessed through the recently discovered northern stone gates that run vertical to the eastern wall of the Aqṣā mosque. Many of the walls, pillars and arches of the Marwānīd Prayer Hall (particularly in the riwāq abutting the eastern wall of the Aqṣā mosque) already suffer from a poor condition of reservation. They show many cracks as well as significant buildup of dust and dirt residuals because of increasing moisture. This situation calls for urgent solution.

The pre-Islamic history of the subterranean vaulted space, i.e. the Marwānīd Prayer Hall, is greatly disagreed upon. Equally disagreed upon is whether this space, that served as an armoury and horse barn during the Crusades (particularly in the reign of Baldwin II), was used for Muslim prayer as early as the Umayyad period. From ‘stable’ to ‘prayer hall’, the name of the places, like many other aspects of this holy site, is laden with implications. It bears the traces of a renowned medieval conflict between two prominent civilizations in its stones. The rings to which the horses were reportedly tethered can still be seen in the pillars of the Muṣallā. The Marwānīd Prayer Hall is said to have been cleaned and then closed when Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn recaptured Jerusalem. In the West this space is typically called the Solomon’s Stables.

What’s in a Name?

This leaves us with a final set of questions. This place, which has been contested, is called many things by different people—many of whom believe it to rightfully be one thing, belonging to one people, or from one historical period only.

But whether the holy site is better described as the Temple Mount, Mount Moriah or al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf,

whether the Marwānīd Prayer Hall were stables that were turned into a prayer space or vice versa,

whether it assumed the character of a prayer space lies in how it looked in 1996 or in its earliest Islamic years,

whether the platform that pre-existed its construction was built by the Umayyads to level up the sloping southern part of the holy site or by King Herod to extend the platform of the Temple Mount southward onto the Ophel

… all remain rather secondary to the fact that we are dealing with a notable historical site that is used for prayer and thus assumes an exceptional religio-cultural significance for many.

Like Notre Dame, the Aqṣā mosque means many things to many people. Its long and complex history is written in its stones, its furnishings, its spaces. In April, the Aqṣā mosque may have dodged a proverbial bullet. But at the very least, this may offer the opportunity for more people to know this magnificent edifice, and its history, a little better.

If you enjoyed that article, please share it with your history-loving friends on Facebook, or on Twitter! And be sure to subscribe here to receive every new article from The Public Medievalist the moment it launches.